Archeological texts often list “perforated bone tubes” among artifacts unearthed from early humans’ caves and burial sites. “Perforated bone tubes,” in its clinical language, is a name that aims to describe the artifacts without assigning function. Archeologists theorize that these bones may have been brought to one’s lips and used as whistles or bird calls. Objects made for utility, for drawing birds from the air during a hunt. Maybe this is so. Yet, they could also be interpreted as flutes — things made to please the soul.

Such artifacts may hold evidence of human minds awakening to music — signs of our ancestors turning bone and air into song and of an ancient ability to feel beauty piercing our chests. An innate yearning to be beauty’s mimic.

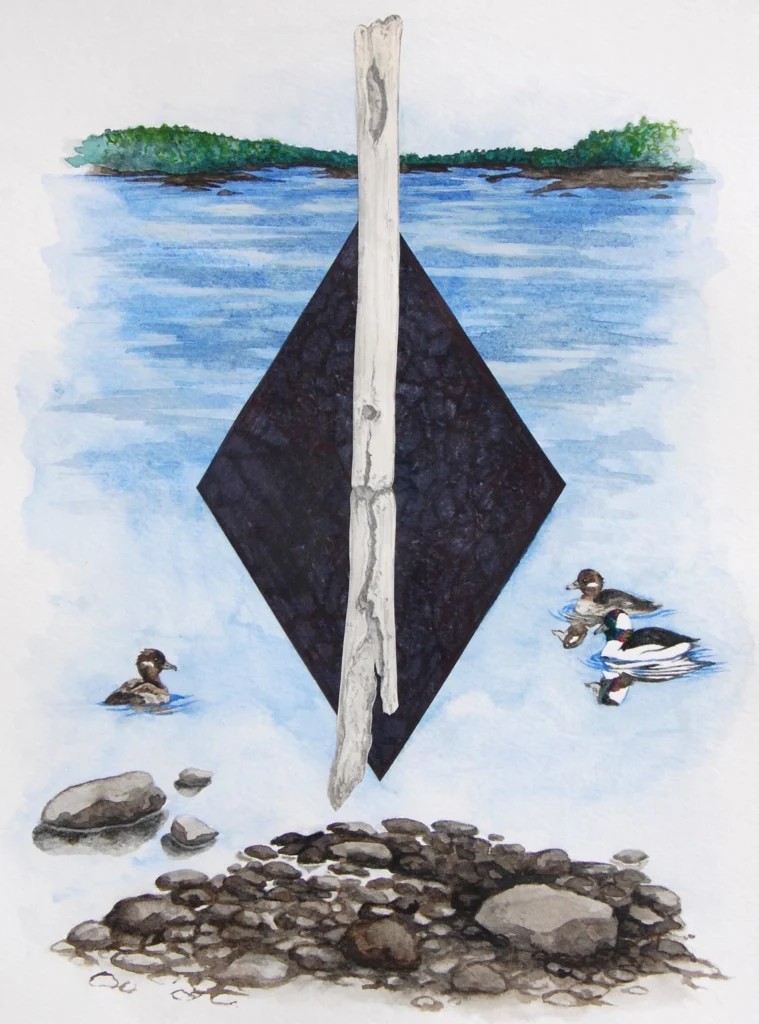

One late January day, I visited a grassy point overlooking the bay on the west side of Maine’s Schoodic Peninsula. The Point, within Acadia National Park boundaries, has picnic tables, fire rings, and a pier jutting out into the water. The wind had swept a recent snowfall into drifts along the field. A few Buffleheads bobbed in the turning tide’s cobalt waves. I walked along the cobble shore, studying the edges of the field that are crumbling into the water.

Archeologists found a perforated bone tube at this place in 1978. They excavated it along with tools, bits of pottery, mammal and bird bones, and soft clam shells — traces left by the ancestors of the Wabanaki. Meaning “People of the Dawnland,” Wabanaki is the collective name for the tribes — the Maliseet, Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot — who live in what is now Maine and the Canadian Maritime provinces, their indigenous homeland.

Wabanaki ancestors lived on Schoodic Peninsula, hunting and gathering food at the Point long before it became a place where tourists like me eat their turkey sandwiches and potato chips.