Overview

About

Although at least five crow species historically occurred throughout the Hawaiian Island archipelago, the ʻAlalā, or Hawaiian Crow, is the only one that still exists today. One of the rarest corvids in the world, the ʻAlalā was declared Extinct in the Wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature in 2002, after researchers had taken the last wild individuals into captivity in order to save the species. The ʻAlalā is also federally and state-listed as Endangered.

Like other members of its family, which includes the American Crow and the Common Raven, the ʻAlalā is a noisy, sociable, and highly intelligent bird. Its Hawaiian name means “to cry out loud,” an accurate description of its vocal personality. Native Hawaiians consider the ʻAlalā to be an ʻaumakua (family or personal god), and its feathers were sometimes used ceremonially.

Threats

Birds around the world are declining, and many of them, like the ʻAlalā and other Hawaiian forest birds, are facing urgent, acute threats. Hawaiʻi’s birds have been hit especially hard by a suite of threats ranging from habitat loss to introduced mosquitoes. Scores of species have already been lost, and the situation is dire for many of those that remain.

Habitat Loss

Former ʻAlalā habitat has been destroyed and severely degraded by human settlement, non-native livestock such as cows, goats, sheep, and pigs, and introduced invasive plants. These changes limited food and nesting resources and increased the ʻAlalā’s vulnerability to predation.

Cats & Invasive Species

Introduced predators such as feral cats, rats, and the small Indian mongoose prey on ʻAlalā, especially on their eggs and young. The ʻIo (Hawaiian Hawk) also preys on juveniles and adults, and has been one of the significant problems with previous reintroductions of captive-reared birds into the wild on Hawaiʻi Island. ʻAlalā are vulnerable to diseases carried by introduced mosquitoes, such as avian malaria and avian pox, and to toxoplasmosis carried by non-native, feral cats.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

Bringing back the ʻAlalā will be a decades-long process, with maintaining its population in human care as the first step. In the late 1970s, the last wild ʻAlalā were taken into a captive breeding program headed by the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance at the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center on Hawaiʻi Island, and the Maui Bird Conservation Center. This partnership includes the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources–Division of Forestry and Wildlife, and many other partners.

Attempts to reintroduce ʻAlalā into the wild in the 1990s and from 2016 to 2019 resulted in high mortality rates, and surviving birds were returned to captivity. In late 2024, ABC partner Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project released five young ʻAlalā on the slopes of Haleakalā in the Kīpahulu Forest Reserve on Maui. This release site was chosen because there are no ʻIo on Maui, which had disrupted previous reintroduction efforts on Hawai’i Island.

ABC is part of an integrated campaign with many partners to tackle the threats facing the birds of Hawaiʻi, which are also representative of threats to birds everywhere: habitat degradation, invasive species, and non-native predators. We envision a future where Hawaiʻi’s birds are not just avoiding extinction, but are thriving. Our work supports the long-term recovery of the ʻAlalā as this precious group of birds returns to the wild.

Stop Cat Attacks

Cats make wonderful companions, but they’re safest (and birds are, too) when they’re kept indoors or under the control of their owners. ABC advocates for responsible cat ownership and for policies that benefit birds, cats, and human health. We have supported policy initiatives to address the threats of free-roaming domestic cats in Hawaiʻi, and have worked with partners to construct predator-proof fencing at key nesting areas to protect Hawaiian birds.

Control Mosquitoes

ABC belongs to a multi-agency partnership, Birds, Not Mosquitoes, that is deploying non-biting, lab-reared male mosquitoes carrying a naturally occurring bacteria that results in sterile eggs when the released males mate with wild females. With time, the population of invasive, malaria-carrying mosquitoes will be reduced in Hawaiʻi.

Bird Gallery

The ʻAlalā is the largest surviving Hawaiian forest bird, weighing about a pound and measuring about 1.5 feet long from bill to tail. This medium-sized crow is a duller black than its North American cousins, with brownish wings and stiff, hairlike throat feathers that the bird can erect during breeding displays. Its thick, arched black bill has long bristly feathers covering the nares (nostrils). Strong, gray-black legs and feet allow the ʻAlalā to cling to vertical branches and even hang upside down.

Both sexes look alike, but male ʻAlalā are larger. Young ʻAlalā have bright blue eyes, which become brown with adulthood. Nestlings and fledglings have bright red mouth linings which turn black with age.

Sounds

The ʻAlalā utters a wide range of vocalizations, from shrieks, yells, whoops, and howls to softer close-contact calls that sound like growls and mutterings. Scienticists have described at least 34 different calls given by this spees. Males are more vocal than females, with the loudest and most complex calls given by males during territory formation and defense. ʻAlalā utter softer calls during roosting, courtship, and pair-bond maintenance.

ʻAlalā by Tim Burr; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

ʻAlalā by Tim Burr; Cornell Lab of Ornithology | Macaulay Library

Habitat

In the wild, the ʻAlalā would be found in wet and mixed native forests.

- Historically found in ʻohiʻa and ʻōhiʻa/koa forests between 1,000–8,200 feet in elevation, and dry-forest habitat with native trees such as ʻōhiʻa, lama, māmane, and naio

- Also found in human-modified habitats, such as agricultural areas

Range & Region

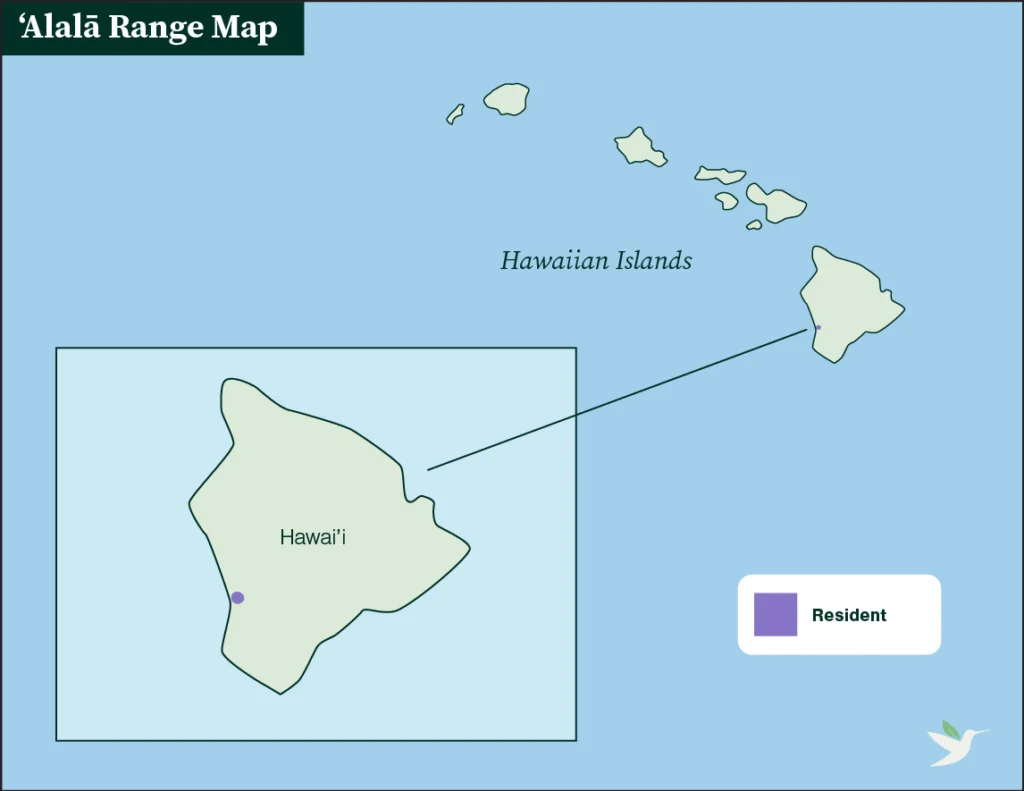

Specific Area

Western and southeastern parts of the Island of Hawaiʻi

Range Detail

Historically, ʻAlalā occupied dry and seasonally wet ʻōhiʻa and ʻōhiʻa/koa forests on the island of Hawaiʻi, where it was endemic before being declared Extinct in the Wild. It may have once occurred on other islands of that archipelago. The last wild birds were recovered from the forested slopes of Hualālai and Mauna Loa Volcanoes on Hawaiʻi Island. Although the species is Extinct in the Wild, core areas of its former range are managed by the State of Hawaiʻi and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Did you know?

Although not a true migratory species, the ʻAlalā had been noted for making seasonal movements in response to weather, breeding season, and availability of food plants such as the ʻIeʻie.

Life History

ʻAlalā are gregarious, remarkably intelligent, and playful birds, usually seen in pairs or family groups. They form lifelong bonds with each other. A 2016 study published in the journal Nature showed that the ʻAlalā, like another intelligent tropical corvid, the New Caledonian Crow, makes and uses tools while foraging for food.

Diet

ʻAlalā have a largely frugivorous diet of native and introduced fruits, plus invertebrates, and the eggs and nestlings of other forest birds. They may also consume nectar, flowers, and carrion. In the wild, ʻAlalā are ecologically important as seed dispersers for many native plant species.

Courtship

ʻAlalā engage in a variety of courtship displays that include mutual preening, courtship feeding, strutting, and tail-wagging. Early in the breeding season, pairs perform synchronized, spiraling flights, flying wing-to-wing or very close together.

Although individuals usually form long-term pair bonds, extra-pair copulations have been observed.

Nesting

The ʻAlalā usually builds its nest in a native ʻōhiʻa tree. The nest is a large, loose bowl of sticks lined with moss, grass, rootlets, and other fine materials. While both the female and male participate in nest construction, only the female incubates the eggs and broods the hatchlings.

Eggs & Young

The female ʻAlalā lays a clutch that ranges from one to five pale, blue-green eggs, which are speckled in darker brown. The naked, helpless young hatch with eyes closed. They grow quickly, and are soon begging loudly for food. The young birds fledge after an average of six weeks in the nest. The fledglings typically do not fly well and may remain near the ground for periods of time, which can increase their susceptibility to diseases such as toxoplasmosis and predation. Young ʻAlalā remain dependent on their parents for at least eight months and stay with their family group until the following breeding season.