Overview

About

The Canada Jay is a bird of many evocative nicknames, including Camp Robber, Gorby, and Whiskyjack. The first two names refer to this bird’s exceptionally fearless, bold behavior around humans. “Gorby” is thought to derive from the Scots-Irish word gorb, meaning “glutton.” Folklore told that a gorby was the soul of a dead woodsman, and that any harm done to a gorby rebounded upon the person who harmed the bird.

Clever, curious, and opportunistic, the Canada Jay is incredibly tame and very bold around humans. Some Canada Jays will even land on a person’s outstretched hand … if that outstretched hand is offering food! Among the many nicknames reflecting the Canada Jay’s charisma, one common nickname, “Whiskyjack,” is an anglicization of the Algonquin word Wisakedjak, the name of a benevolent trickster god and principal character in the creation myths of several First Nations cultures.

Canada Jays are as tough as they are clever. They have to be in order to survive year-round in boreal and subalpine forests, where temperatures plummet and most winter days are below freezing. Canada Jays are prepared for the cold: They cache food throughout the year, stashing it under tree bark or lichen. (Remarkably, they remember where they left it!) This challenging existence is now being exacerbated by the impacts of climate change on the Canada Jay’s habitat and range.

Threats

Birds around the world are declining, even hardy species like the Canada Jay, built to withstand tough conditions. Climate change, habitat loss, and invasive species are making the Canada Jay and other boreal forest birds more vulnerable. This curious jay also falls victim to traps set for fur-bearing mammals.

Habitat Loss

The Canada Jay’s range is expected to continue to shift northward, following the trajectory of the boreal forest, which is shrinking to the south but expanding to the north.

Climate Change

A rapidly warming climate has led to outbreaks of destructive insects such as the Mountain Pine Beetle, which destroys lodgepole pine habitat used by Canada Jays. Warmer weather also ruins this jay’s vital winter food stores.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

At ABC, we’re inspired by the wonder of birds like the intrepid Canada Jay, and we’re driven by our responsibility to help birds overcome the threats they face. Working in partnership and with science as our foundation, we take action for birds across the Western Hemisphere.

Restoring Habitat

ABC’s Great Lakes habitat conservation team works to restore and enhance forests for birds of that region, including in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The team works with federal, Tribal, state, and local partners to improve habitats on both public and private lands.

Addressing Climate Change

ABC addresses climate change in three key areas: mitigation, resilience, and adaptation. We have planted millions of trees throughout the Western Hemisphere, protected more than 1 million acres of land in Latin America and the Caribbean, and continue to improve and restore bird habitat.

Supporting Petitions & Advocacy

The kind of large-scale, science-based planning needed to conserve birds is made possible, in part, by policy decisions at the state and federal levels. We advocate for enhanced funding for bird conservation and policy initiatives that benefit birds and their habitats.

Bird Gallery

The Canada Jay is a large, long-tailed bird, almost the size of a Blue Jay, but lacking a crest. Its plumage is a muted mix of gray and white, with varying amounts of black on the head, depending on the subspecies (nine are recognized). The throat and face are white, and the black bill appears short due to feather-covered nares (nostrils), an adaptation to its cold climate. Its legs and feet are black. Juvenile Canada Jays are a distinctive dark gray, becoming lighter as they age.

Sounds

Although not as vocal as other family members, such as the Steller’s Jay or Common Raven, the Canada Jay still produces a variety of calls ranging from chatters to whistles. They often mimic predators like Broad-winged and Red-tailed Hawks, Merlins, and American Goshawks, perhaps to confuse them or communicate the threat to other Canada Jays.

Yoann Blanchon, XC826904. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/826904.

Andrew Spencer, XC149242. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/149242.

Andrew Spencer, XC22396. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/22396.

Habitat

The Canada Jay is found in coniferous and mixed coniferous-deciduous boreal forests from tundra to treeline.

- Preferred coniferous habitats contain spruce (black, white, red, Engelmann, Sitka), fir (balsam, alpine, silver), and jack and lodgepole pine

- Mixed forests used include deciduous trees such as quaking aspen, white birch, sugar maple, and eastern white-cedar

Range & Region

Range & Region

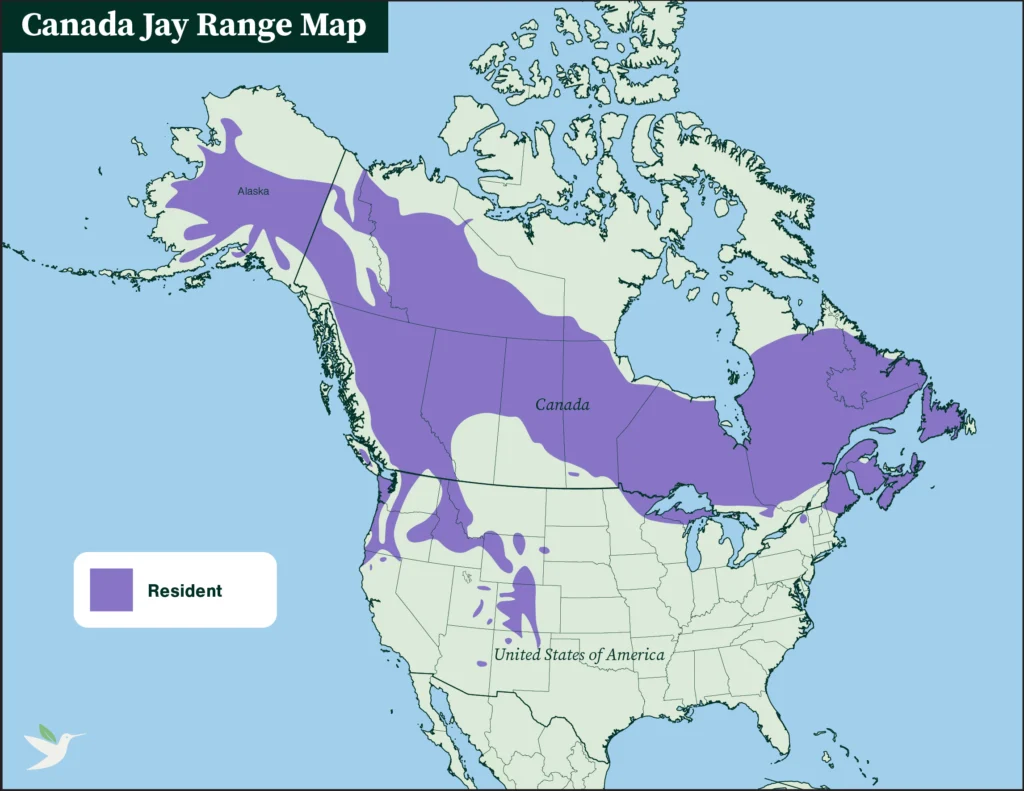

Specific Area

Canada, western mountains and northern areas of the United States

Range Detail

The Canada Jay is a resident of boreal and subalpine forests from Alaska across Canada and in mountain forests of the western U.S. from Washington and Utah to New Mexico and California. It is also found in northern New England (Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont) and the upper Midwest (Michigan and Wisconsin). Isolated populations exist in the Black Hills of South Dakota, the White Mountains of Arizona, and the Adirondack Mountains of New York.

Did You Know?

Though the Canada Jay is mostly nonmigratory, the species experiences “irruptions,” moving in large numbers to the south, outside of its normal range. These movements are usually in response to low food supplies.

Life History

Canada Jays are fearless, especially when it comes to food. Their tendency to raid campsites has earned them the nickname “Camp Robber.” They’re generally curious birds, known to follow along as people hike through the woods, taking short flights from one tree to the next and watching their fellow travelers with interest. They’re often spotted in pairs and are monogamous. Built for winter, the Canada Jay has many adaptations that allow it to withstand brutal winters in the boreal forest: extra fluffy feathers for insulation, feathers even on the nostrils, and a food caching strategy to stay fed all winter. They even use winter to their advantage by breeding in the frigid temperatures to get a head start on food caching.

Diet

Their food caching strategy (known as “scatter-hoarding”) helps Canada Jays survive the winter. They coat bits of food with sticky saliva produced by extra-large salivary glands, then fasten them under tree bark or lichen, or in the forks of trees or amid conifer needles. Unlike most songbirds, Canada Jays sometimes carry food with their feet, allowing them to quickly remove food before competitors arrive. Canada Jays take insects, spiders, ticks, berries, carrion, nestlings and eggs, small mammals, salamanders, fungi, and birdseed and suet.

Courtship

The Canada Jay is monogamous, with pairs remaining together for life. If one bird disappears, the other will seek a new partner. Pairs stay together year-round in their territory, even maintaining contact using calls as they forage or retrieve cached food. Courtship behaviors include tail-wagging displays performed by both males and females, touching bills, and mutual feeding.

Nesting

The male Canada Jay chooses a nest site, usually in a conifer, and begins the building process, with the female soon joining in. The nest is a bulky platform of spruce and tamarack twigs. The jays fill spaces in the outer nest layer with cocoons. The female jay finishes the nest with a soft, insulating layer of hair from deer and snowshoe hares. They tend to select nesting spots in the southern edges of their patch of forest, allowing them to take advantage of the sunlight.

Eggs & Young

For roughly two and a half weeks, the female Canada Jay incubates a clutch of two to four pale greenish-gray eggs. Once they’ve hatched, the female initially broods the young while her mate brings food. Eventually, she begins to leave the nest to acquire food. Hatchlings quickly grow a layer down, then their juvenile feathers, leaving the nest around 23 days after hatching.

Young Canada Jays stay in their parents’ territory until early summer. At that time, the most dominant fledgling drives its siblings out of the territory, a phenomenon known as “true brood reduction.” This tactic gives the strongest fledgling exclusive access to its parents’ food caches. The ejected siblings often try to join with unrelated pairs that did not nest successfully. Juvenile Canada Jays stay in their birth or adopted territories until they are old enough to breed.