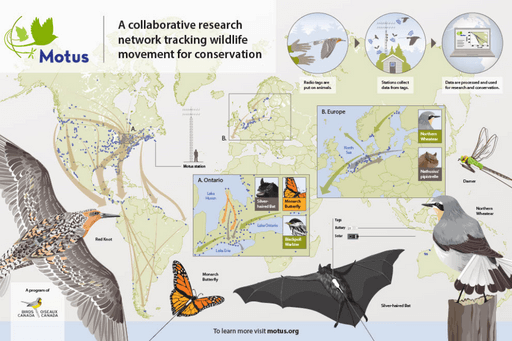

Motus (Latin for “movement”) is a wildlife tracking network using automated radio telemetry. It was launched in 2014, soon became a program of Birds Canada, and has rapidly spread with the help of hundreds of collaborators. To date, more than 1,500 Motus receiver stations have been installed across 34 countries, though most towers are still concentrated in the U.S. and Canada, where the network began.

The Motus network has spread so quickly because it bundles a few key elements that make it broadly useful for researchers and conservationists. One of these benefits is the miniscule size of the radio tags used. They can weigh as little as one-tenth of a gram, the weight of a single pine nut. There aren’t many other tagging options that are lightweight enough to fit on a warbler — or even a dragonfly — while transmitting data to enable real-time tracking.

Geolocators and GPS loggers, for instance, are lightweight but only store data. They can’t transmit it. That means scientists have to recapture tagged birds to get information, which only happens in a small fraction of cases. Satellite tags, conversely, can transmit data but are too large to put on anything smaller than a meadowlark. While satellite tags continue to get lighter as technologies improve, the smallest varieties are still at least 30 times heavier than the smallest Motus tags.

“Motus’s sweet spot is tracking small animals — especially migratory birds — over large distances,” said Adam Smith, ABC’s Motus U.S. Director.

Another major benefit of Motus is that the barrier to entry is low. Once an individual or organization acquires the appropriate state and federal permits, they simply need to purchase the radio transmitters that emit the right frequency and affix them on their study subjects. Then, biologists can just sit back and wait for existing towers to “hear” the pings sent out from their bird’s transmitter, which the receivers can pick up from up to 10 miles away. The data collected is then not only available to the researchers, but shared on motus.org for anyone to use.

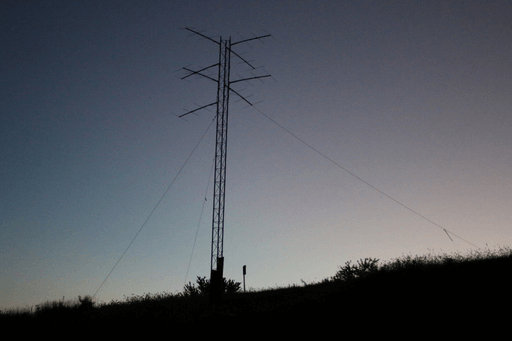

Finally, placing new receiving stations is also relatively straightforward. Pretty much anyone can put up a receiver station if they have suitable funding and a site with good, clear line of sight for the radio antennas. There are Motus stations on wildlife refuges, zoo grounds, and even private ranches, to name a few locations.

However, because the network is still expanding, there are many gaps in Motus receiver coverage. In order to best use Motus’s capabilities to understand when and how birds use certain habitats, key gaps in the network must be filled. That’s why there are plans in the works to strategically build out the network along key bird migration paths.