Overview

About

Most woodpecker species in the United States and Canada display a mix of black, white, and red plumage, but don’t tell the Lewis’s Woodpecker. Its unusual mix of colors includes a red face, pink belly, glossy green back, crown, and nape, and silver-gray collar. The bird is simply stunning.

Lewis’s Woodpecker also differs from other members of its family in many of its foraging styles and food choices. In the summer, the bird eats mostly insects, catching them in flight by swooping out from a perch like a flycatcher or by foraging in flight like a swallow. Wide, rounded wings give the bird a buoyant, straight-line flight, more like a jay or crow than a woodpecker. The bird seldom excavates for wood-boring insects; unlike other woodpeckers, this species lacks the strong head and neck muscles needed to drill into hard wood.

In the fall, Lewis’s Woodpeckers switch to eating nuts and fruit, chopping up acorns and other nuts and caching them in bark crevices for later consumption. During the winter, they aggressively guard these storage areas against intruders, including other woodpecker species.

Ornithologist Alexander Wilson described the species in 1811 and named it for Meriwether Lewis, who observed the bird in 1805 during the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Threats

Birds around the world are declining, and many of them, like Lewis’s Woodpecker, are facing urgent, acute threats. Moreover, all birds, from the rarest species to familiar backyard birds, are made more vulnerable by the cumulative impacts of threats like habitat loss and invasive species.

Habitat Loss

Surveys indicate that Lewis’s Woodpecker populations may have declined by about 60 percent since the 1960s, and much of the reduction is likely due to loss or alteration of suitable nesting habitat. Like all other woodpeckers, the Lewis’s Woodpecker requires cavities in snags (standing, dead, or partly dead trees) for nesting. Logging, the suppression of wildfires, and grazing have altered many of the western forests where the species is found. The changes to the landscape often result in large areas dominated by trees that are the same age, leaving few dead or decaying trees available for the birds’ nests.

Pesticides & Toxins

Pesticides take a heavy toll on birds in a variety of ways. Birds can be harmed by direct poisoning from pesticides, lose insect prey to pesticides sprayed on crops and lawns, or be slowly poisoned by ingesting small mammal prey that have themselves ingested rodenticides. Lewis’s Woodpeckers are likely exposed to pesticides in orchards and other agricultural settings.

Climate Change

A changing climate presents a suite of often unpredictable threats to birds: extreme weather events, droughts, habitat loss due to rising sea levels, and intense heat are just a few ways climate change puts birds at risk. Birders in British Columbia, for example, report dramatic declines in Lewis’s Woodpecker numbers due to large fires. In addition, the warming climate has increased the extent and severity of pine beetle outbreaks in parts of the woodpecker’s range. Infestations of the beetles kill ponderosa pines in large numbers; this leads to a short-term supply of decaying trees that the woodpeckers can nest in, but the trees fall within a few years of dying, producing dramatic losses in the availability of nest trees. Future climate change scenarios suggest more infestations will happen in other parts of the bird’s range.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

Birds need our help to overcome the threats they face. At ABC, we’re inspired by the wonder of birds and driven by our responsibility to find solutions to meet their greatest challenges. With science as our foundation, and with inclusion and partnership at the heart of all we do, we take bold action for birds across the Americas.

Restoring Habitat

For many years, ABC has worked to conserve the Lewis’s Woodpecker and other cavity-nesting birds, including Flammulated Owl and Williamson’s Sapsucker, on private ponderosa pine lands in the Pacific Northwest. We previously helped the Columbia Land Trust purchase 115 acres of a 418-acre wildlife corridor on Mill Creek Ridge in north-central Oregon. We’ve also connected landowners in the West to ABC-authored guides to maintaining their lands for cavity-nesters like the Lewis’s Woodpecker.

Scientific Research

In the U.S., ABC guides the work of the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, an international program of Birds Canada that has revolutionized scientific knowledge about animal migration. More than 470 species, including the Lewis’s Woodpecker, have been tracked with the small tags used by Motus. Researchers are using Motus to better understand the movements of the woodpeckers in western regions in hopes of improving conservation outcomes for the bird.

Bird Gallery

This woodpecker’s unique mix of colors is stunning when viewed in good light. It has a red face, pink belly, glossy green back, crown, and nape, along with a silver-gray collar. From a distance, it can look mostly dark. Juveniles are browner overall.

Sounds

Unlike other woodpeckers, the Lewis’s is relatively quiet. It primarily calls and drums only during the breeding season. Males make a churr call 3-8 times in a row, often during courtship. The birds also use a short chatter call and make a simple squeak note as an alarm call.

Andrew Spencer, XC13659. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/13659.

Ron Overholtz, XC575042. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/575042.

Mark A. Ports, XC700388. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/700388.

Habitat

The Lewis’s Woodpecker relies on open coniferous forests, mature riparian and oak forests, and burned areas.

- Main breeding habitats include open ponderosa pine forests, open riparian areas with cottonwoods, and areas that have been burned or logged

- Oak woodlands, nut and fruit orchards, piñon pine–juniper woodlands, and agricultural areas also attract breeding birds

- Nonbreeding habitats include oak woodlands, orchards, areas with cottonwoods, and power poles that the bird uses to cache mast or grains

Range & Region

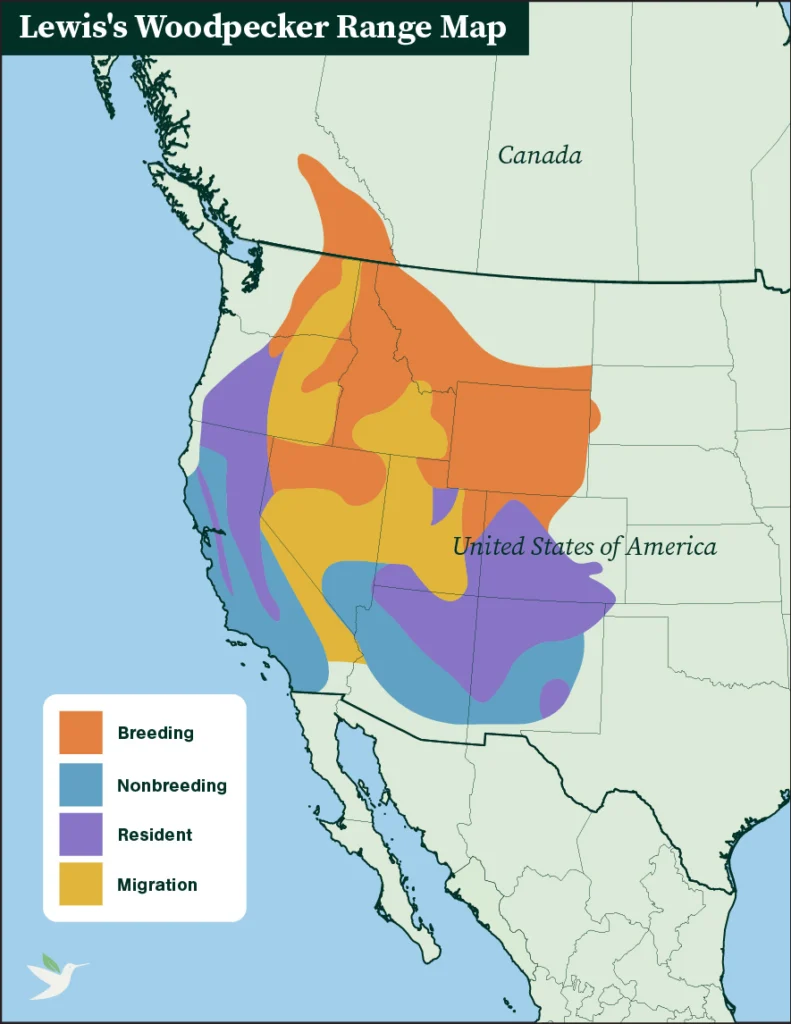

Specific Area:

Central British Columbia, western Alberta, central Washington, western Oregon to western Montana, central California to eastern Colorado and central New Mexico.

Range Detail:

The Lewis’s Woodpecker is sparsely distributed across a wide range of western North America — from southern British Columbia and western Alberta to areas along the U.S./Mexico border. The range, which is similar to that of the ponderosa pine, extends from near the Pacific coast to western South Dakota, eastern Colorado, and south-central New Mexico. Vagrants sometimes wander east into the Great Plains and Midwest and rarely as far as New England and eastern Canada.

Did you know?

Outside of the breeding season of late April to mid-August, the Lewis’s Woodpecker’s movements are somewhat unpredictable. Birds in northern breeding areas migrate south in late August or early September and arrive in wintering areas by mid-October. In the nonbreeding season, the birds are nomadic and make opportunistic movements in search of food. In some areas, after young leave the nest, the birds move from valleys to higher elevations in early fall, then head to lower elevations before winter.

Life History

The lives of Lewis’s Woodpeckers appear to be anything but routine. Their diet varies by season, they can nest in live and dead coniferous and deciduous trees (and utility poles), and they aren’t strongly territorial about nest sites. And as mentioned above, they’re nomadic in the nonbreeding season.

Diet

In the summer, Lewis’s Woodpeckers feed on insects that they catch in flight. In the fall, they seek out nuts and fruit, chopping up acorns and other nuts and caching them in bark crevices for later consumption. During the winter, they aggressively guard these storage areas against intruders, including other woodpecker species.

Courtship

During courtship, males call and drum, lift their wings, and fly around their chosen nest trees, finishing by landing at the entrance to their nest holes, to attract females. The birds begin to court as soon as they arrive at their breeding areas, usually in May.

Nesting

Like all other woodpeckers, Lewis’s requires cavities in snags (standing, dead, or partly dead trees) for nesting. Since they lack the ability to excavate, the birds tend to choose trees that are already well-decayed. Even so, they rarely, if ever, excavate the holes themselves, instead re-using a cavity made by another bird or animal.

Eggs & Young

After lining the hole with wood chips, the female lays a clutch of 5 to 9 eggs. The male incubates at night, while both adults alternate egg-sitting during the day. After 12 to 16 days, the eggs hatch, and then about a month later, the young leave the nest. They remain nearby for at least 10 days, continuing to be fed by the adults during this time.