In 2024, ABC and Re:wild announced a new initiative called the Afrofuturism Collective. While different people define Afrofuturism in different ways, one succinct explanation (via UCLA Magazine) is that it’s “a wide-ranging social, political, and artistic movement that dares to imagine a world where African-descended peoples and their cultures play a central role” in creating a better future for Black people — and everyone.

Well-known examples of Afrofuturistic work include the music of artists such as Sun Ra and Earth, Wind, and Fire, the sci-fi novels of Octavia Butler, the Marvel superhero Black Panther, and many others. Our Afrofuturism Collective, which has nine members, aims to contribute to the genre by focusing on environmental issues — and birds especially.

We recently spoke with Naamal De Silva, ABC’s Vice President of Together for Birds, and Binta Dixon, a facilitator for the Collective, about the project.

What was your inspiration for the Afrofuturism Collective?

Naamal: Growing up in Washington, D.C., I was surrounded by art and culture connected to Africa. Later, I worked on identifying priority habitats for threatened species in east and southern Africa. In 2023, I attended a remarkable Afrofuturist exhibition by artist Ayana V. Jackson and wondered how such creativity could enrich conservation. I soon proposed the Collective to Nina Paige Hadley and Penny Langhammer of Re:wild, who became wonderfully supportive funders of the initiative.

While ABC and Re:wild both depend on the natural sciences to guide much of our work, the arts and storytelling can help us better understand and articulate why we care for birds, ultimately creating a deeper sense of compassion and care for birds, human communities, and ourselves.

How did you become involved?

Binta: Naamal invited me to participate in a Together for Birds project to share my experience of life transitions and connecting to birds. I’m a student of nature and Afrofuturism and currently an Advocacy Coordinator for ABC.

When the opportunity to support the Collective as its coordinator came up, I was thrilled to be a part of this work that felt so aligned with the projects and artistic practice I’ve participated in for years.

What is the Collective doing?

Naamal: Each member of the Collective received a small stipend to carry out an independent project related to how some aspect of Afrofuturism might enable work for biodiversity and the environment to become more effective, inclusive, and ethical. Members of the Collective have different lived experiences, areas of expertise, and modes of creative expression.

The projects themselves are varied, ranging from creative works such as essays, poems, videos, or visual art to more technical products that foster and document community engagement and collective learning. In my mind, the Collective is seeking answers to a question by the late author and social critic bell hooks: “Can we embrace an ethos of sustainability that is not solely about the appropriate care of the world’s resources, but is also about the creation of meaning — the making of lives that we feel are worth living?”

What are the Collective’s gatherings like? What are some key insights you have gained so far?

Binta: The Collective holds regular virtual meetings. The gatherings are a space to slow down and dream of new possibilities we can put into motion. These gatherings illuminate how important it is for us to include ourselves and our well-being as we work to regenerate and protect healthy ecosystems. Afrofuturism is a supportive lens to consider how culture and identity impact the ways we think of our positionality within the natural world.

We are learning as a collective that the best way to understand Afrofuturism is to reflect on its current uses and ask questions. Through this process of inquiry, we can add to its intricate web by examining Earth stewardship practices found across the Diaspora, considering what aspects of those practices are useful now, and imagining how we can build upon them for future stability, harmony, and community health.

Afrofuturism asks us to pull forward practices from the past and consider how they can be adapted for present-day and future use. I hope that having technical and artistic projects created in the same space can give life to new visions that future cohorts of the Collective, communities engaged in conservation work, and generations of environmentalists use to propel their initiatives forward with greater support and resources.

A Symbolic Logo

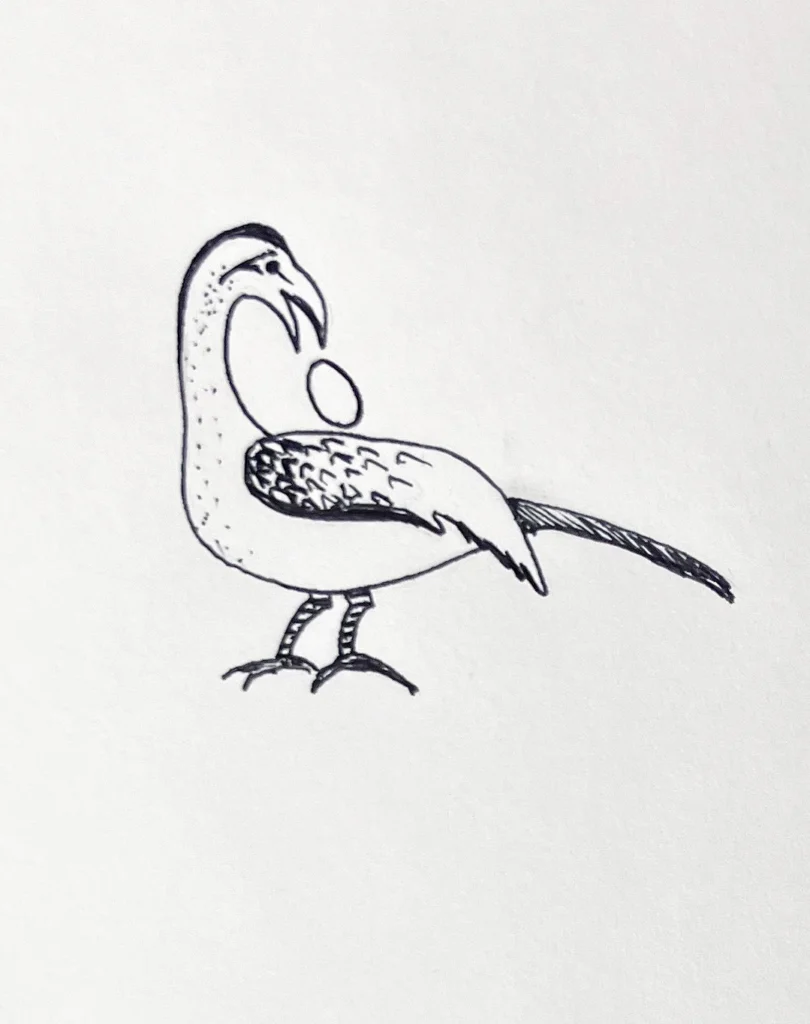

Sankofa is the English adaptation of two Twi words from the Akan people of Ghana. They are derived from a proverb: “Se wo were fi na wosan kofa a yenkyiri.” Translation: “It is not taboo to go back for what you left behind.”

Sankofa is often recognized through its Adinkra, a symbol that signifies a core piece of wisdom within Akan culture and across Ghana. Although there are hundreds of Adinkra, Sankofa is the most widely known across the African Diaspora. For those in the Diaspora who were forcibly removed from their homelands, it often signifies the journey to reconnect with their African heritage.

The Sankofa Adinkra’s most recognizable symbol is a bird reaching back for an egg. Given the significance of birds in African Indigenous cultures and worldwide, is it possible that the symbol represents the Western Long-tailed Hornbill, a bird found in Ghana and across the Western Coast of Africa? Whether the Sankofa represents an actual species or not, we’re proud to adapt it into the Afrofuturism Collective’s logo.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Bird Conservation, the Member magazine of American Bird Conservancy. Learn more about the benefits of becoming an ABC Member and join today.