The Osprey is a large black-and-white hawk with long narrow wings, long legs, and a distinctive M-shaped flight profile. It is found on every continent except Antarctica; its diet and affinity for coastlines have earned it the nicknames “sea hawk” and “fish hawk.”

The Osprey is a large black-and-white hawk with long narrow wings, long legs, and a distinctive M-shaped flight profile. It is found on every continent except Antarctica; its diet and affinity for coastlines have earned it the nicknames “sea hawk” and “fish hawk.”

One of many bird conservation successes made possible by the regulation of pesticides, the Osprey has made a heartening comeback since the 1970s. Organochlorine pesticides, particularly DDT, had depleted Osprey populations by thinning the birds' eggshells, wreaking havoc on nesting success.

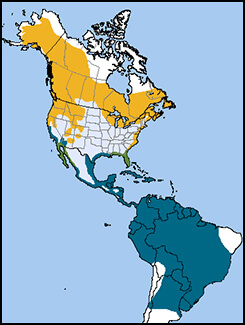

Worldwide, there are four subspecies of Osprey, differing only slightly in size and appearance. North American Osprey populations are migratory, traveling long distances to winter as far south as southern South America. Ospreys are found in Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and in the Caribbean throughout the year, since a reliable year-round food supply makes migration unnecessary.

When young Ospreys make their first migration south, they usually remain in the vicinity of their winter home until they are almost two years old. If they survive to the spring of their second year, they head north, but don't necessarily return to their birth nest.

Packing a Fish Lunch

Fish make up the majority of an Osprey's diet, and they will take almost any size and type. Their eyes are adapted to detecting fish underwater from 30 to 130 feet in the air. When prey is first sighted, the bird hovers momentarily, then plunges feet first into the water, sometimes submerging entirely. Unable to dive to more than about three feet below the water's surface, Ospreys tend to hunt in shallow waters.

In medieval times, fish were thought to be so mesmerized by the Osprey that they turned belly-up in surrender; this is referenced by Shakespeare in Act 4, Scene 5 of Coriolanus: "I think he'll be to Rome / As is the osprey to the fish, who takes it / By sovereignty of nature."

The Osprey has other adaptations that suit its fish-eating diet: reversible outer toes, long talons, and barbed pads under their toes that help the bird hold on to slippery fish. Closeable nostrils keep water out during dives, and dense, oily plumage keeps feathers from getting waterlogged.

When flying with prey, an Osprey lines up its catch head-first for less wind resistance, a behavior often referred to by birders as “packing a lunch.”

Nesting Neighbors

Ospreys reach sexual maturity and begin breeding around the age of three to four, usually mating for life. In some regions with dense Osprey populations, such as the Chesapeake Bay, young birds may not start breeding until five to seven years old. If there are no suitable nesting sites available, young Ospreys may be forced to delay breeding.

Osprey pair at nest by Tom Middleton, Shutterstock

Like the Bald Eagle, this hawk builds a big, bulky stick nest that may be re-used and added to year after year. The male selects a site, then both male and female collect sticks and other materials to build the nest. Often built on poles, channel markers, and dead trees, nests may also be built on nest platforms designed and built for them. These birds habituate easily to human activity and often nest close to busy highways, ports, and marinas.

The female lays up to three eggs, which both parents help to incubate. Osprey egg-hatching is staggered in timing, so that some of the chicks are older and more dominant. The male does all of the hunting until the chicks are six weeks old, delivering fish to the female on the nest, who tears off pieces to feed to the young. When food is scarce, stronger chicks may take it all and leave their siblings to starve–a behavior that some people find disturbing yet ensures that the genetically healthiest bird survives.

At three to four weeks of age, Osprey chicks start to exercise their wings by holding on to the edge of the nest and flapping. The female then moves to a nearby perch to guard the nest. She may leave the nest to hunt when the chicks are six weeks old and begin to feed themselves.

Osprey on the Rebound

Ospreys have rebounded significantly in recent decades, following the U.S. ban on DDT in 1972 enacted by the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency. This ban helped recover populations of other fish-eating birds as well, including Brown Pelican and Wood Stork. The provision of artificial nest platforms has also been important in allowing Osprey populations to expand.

Read more about the contributions of the EPA to bird conservation and and why we're so concerned about current Congressional threats to the agency.

Donate now to support ABC's conservation mission!