How to Make Park Buildings Safer for Birds, One Window at a Time

National Park Service scientists looked at ways to reduce bird collisions with glass in national parks. They show how small actions can have big outcomes.

Wild birds are beloved by many people, and they contribute far-reaching economic, ecological, and human health benefits. Yet researchers estimate that North American bird populations have declined by about 30 percent over the last 50 years. There are three billion fewer birds in the air today than in the 1970s. One of the many reasons for this decline is windows and other reflective surfaces, which kill about one billion birds every year in the U.S. alone. Although glass-covered city skyscrapers certainly play a role, almost half of bird-building collisions occur on buildings shorter than four stories, which applies to most national park buildings. Some of these, like visitor centers, have large glass windows for viewing the landscape and are located in excellent bird habitat — a deadly combination.

The good news is that there are inexpensive, scientifically sound, effective methods to dramatically reduce bird-building collisions. These techniques were often tested in a controlled environment like a shipping container, so they couldn't account for all the things that could happen in an outdoor park setting with buildings. But by exploring these methods, scientists from the National Park Service developed a way to address bird-building mortalities across the agency. Parks that institute these measures can inspire visitors to do the same.

An Iconic Role Model

In 2001, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 13186, Responsibilities of Federal Agencies To Protect Migratory Birds. This order directs agencies to identify and address actions that unintentionally kill these birds. “The iconic buildings and structures of the National Park Service are institutionalized into the very fabric of our country's natural heritage,” said Eric Kershner, U.S. Fish and Wildlife's Division Chief for Bird Conservation, Permits, and Regulations.

Kershner said parks are the most visited public places in the nation. “By reducing lighting and addressing reflective glass issues on their lands,” he added, “not only is the Park Service creating a safer environment for birds, they're also increasing awareness about this issue with hundreds of millions of people, empowering visitors to make change in their own way.”

Searching for Suitable Solutions

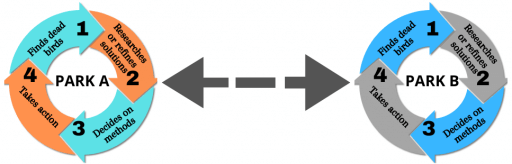

Until recently, the National Park Service lacked an agency-wide strategy to mitigate bird-building collisions. Without such a strategy, each park had to address the issue on its own. The process might look something like this:

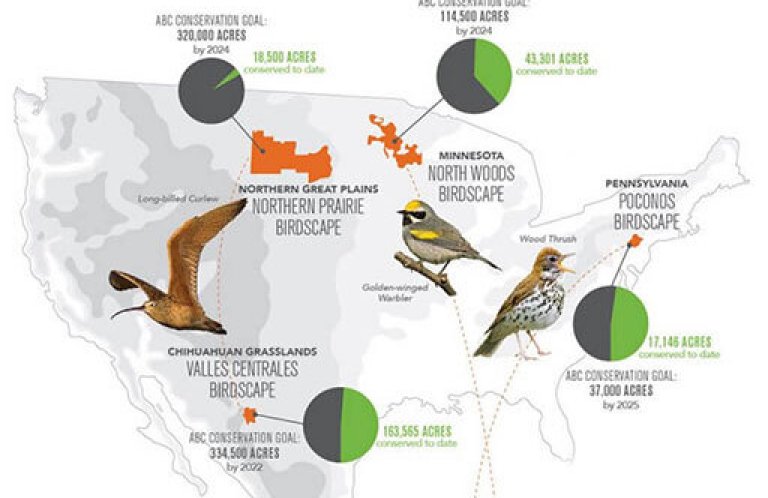

Obviously, this kind of duplication isn't the most cost-effective approach. In 2020, the agency's Intermountain Region partnered with American Bird Conservancy (ABC) to help parks design and plan bird-friendly retrofits to windows. Christine Sheppard, Glass Collisions Program Director at ABC, reached out to 11 interested parks, explaining the issue and helping them choose effective retrofit options. She said the conservancy and the National Park Service are “natural partners," because "the parks are enthusiastic about making their glass safe for birds, and we have a range of options that they can use.”

Zion National Park, one of the 11 parks, began tracking bird-window collisions reported by staff in 2018. Before December 2021, the park didn't conduct regular surveys to search around buildings for birds that were injured or killed in window collisions. All the reports were incidental, coming from concerned park staff who either heard a window collision or found a dead or injured bird. Even then, not all staff were reporting window collisions. Some park staff removed bird carcasses and placed them in the trash or vegetation away from the building without reporting them. When birds flew away after the collision, the incident was sometimes quickly forgotten. By 2024, Zion recorded 38 birds that died as a direct result of colliding with a window. This number may seem small, but it is deceiving.

To put that “small” number in perspective, nearly 70 percent of all reports were from just four buildings. Those buildings had less than 20 percent of the total area of glass surfaces in Zion National Park. This told park biologists that the number of window strikes was likely much higher. In 2020, after reviewing the scientific literature and consulting with Sheppard, volunteers and staff at Zion took action. They began installing adhesive stickers and finger paints to park residences and to the Emergency Operations Center, treating about 15 percent of the park's windows.

Beyond Tunnel Tests

In 2021, Sheppard connected Zion staff with the developer of an adhesive sticker that reflects ultraviolet light. Although these stickers are barely visible to people, most songbirds can see ultraviolet light. The stickers help birds recognize the windows as solid objects while allowing people to have an unimpaired view of the surrounding landscape. Because the stickers are optically clear, they're suitable for historic structures and visitor centers.

Tunnel tests inside a shipping container at the Bronx Zoo in New York City showed that the stickers were effective at reducing bird-window collisions, but the company that made the stickers was searching for a field test. It donated the cost of labor and materials to the park's nonprofit partner, Zion National Park Forever Project, enabling the park to install this product at the historic Nature Center and the Emergency Operations Center. Prior to these treatments, park staff had incidentally reported six total bird-strike deaths on these buildings over nine months. After the treatments, even with bi-weekly carcass surveys, the park recorded only one window strike on these buildings from 2021 to 2024. The park continues to track bird-window collisions and encourages park staff to report all window strikes and dead or injured birds found around park buildings.

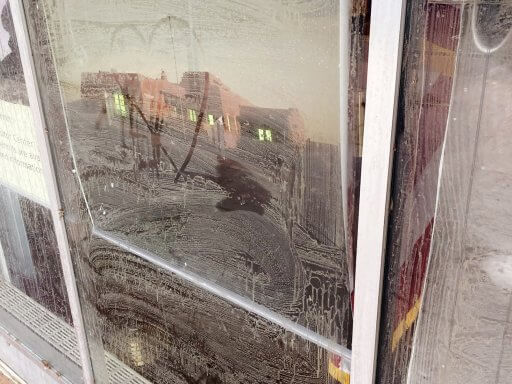

Petrified Forest National Park Superintendent Jeannine McElveen came up with her own innovative solution. She suggested making windows “dirty” by using soapy water until they figured out a more permanent strategy. The dirty windows have worked very well to deter bird strikes. According to internal park records, the park had 51 bird strikes per year for the three years preceding the soap application. After the soap was applied, that dropped to 11 birds per year for the next three years. Though encouraging, these numbers likely aren't exact, as different methods were used to collect them, and the Covid-19 pandemic affected park staff's ability to collect data. The park eventually bought UV-reflective materials. It's installing them on windows of buildings with limited retrofit options, like the modernist style Painted Desert Community Complex, a designated National Historic Landmark.

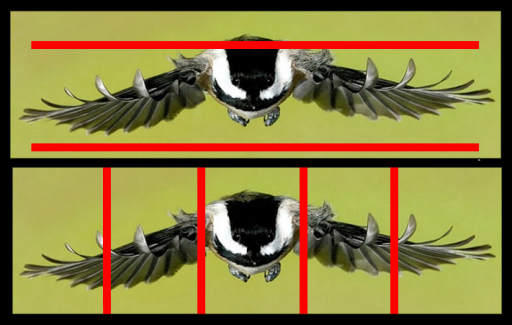

In 2024, American Bird Conservancy wrote Preventing Bird Collisions with Glass: A Solutions Handbook for the National Park Service. This handbook describes bird-friendly glass and 15 different retrofit solutions. The solutions come from tunnel tests that American Bird Conservancy did in a controlled environment. Parks can use this handbook to understand the issue and figure out which retrofit options meet their needs. Solutions range from cheap to expensive; easy to apply to those needing professional installation; and short-term to long-term. There are five main categories of retrofit solutions: dots (non-UV or UV-reflective), stripes (made of cord or tape), film that covers the entire window, paint (free-hand or stencil), and decals. Spacing and placement are critical. Birds are really good at flying through very small openings, so the guidelines say to place the pattern elements no more than two inches apart on the outside of the window to prevent birds from attempting to fly between them.

Long-Term Strategies

The most permanent solution for avoiding bird-building collisions is to design new buildings to be bird friendly. This can be done, for example, by adding awnings or overhangs that limit the reflection of the glass, by angling the glass downward, or by using specially designed glass with built-in patterns that are visible to birds. Although this latter option is initially more costly, it will last for the lifetime of the glass. Solutions applied to the outside of the glass can only be expected to last 7 to 15 years. The Statue of Liberty National Monument's new museum was designed as an extension of the island's landscape in Liberty Park but has bird-friendly glass to avoid confusing the island's winged visitors.

The National Park Service's Biological Resources Division is developing information to help parks protect their wild birds: a document that outlines beneficial practices for bird-window collision mitigation, an internal communications plan, and a strategy for public outreach. Public outreach is especially important, because reflective surfaces in national parks are only one part of a huge national and global problem for our disappearing songbirds. Like Zion, Petrified Forest, and Statue of Liberty, parks that address this problem can inspire visitors to mitigate windows in their own homes, businesses, towns, and countries.

Scientific, park-specific studies of methods to reduce bird strikes could supply additional, valuable data. But parks don't have to wait for the results of such studies to mitigate against bird-window collisions, especially as many don't have the resources to conduct them. There's enough evidence from the science that is out there to show that something (even soap!) is better than nothing to start protecting our disappearing songbirds from reflective surfaces.

Conservation Begins at Home

Of all the threats that birds face, bird-window collisions are one of the easiest for homeowners to help reduce. There are many effective homemade or commercial applications that people can place on windows to avoid bird collisions. But there are even more steps we can all take to save birds:

- Keep cats indoors, confine them in an outdoor space (“catio”), or train them to walk on a leash; scientists estimate that domestic cats kill up to four billion wild birds each year in the U.S. alone.

- Reduce lawns and plant native plants; native-plant landscaping can offer better food and shelter for many birds.

- Avoid pesticides; they can harm birds from contact or contaminated food (seeds and insects).

- Drink coffee that's good for birds; shade-grown coffee protects trees and forests in Central and South America, where migratory birds spend the winter.

- Reduce use of plastics; seabirds can mistake plastic objects as food.

- Watch birds and share what you see; help scientists keep track of how birds are doing through citizen science (sometimes called “community science,” though the terms aren't synonymous), organized bird counts, or apps like eBird.

The problem of disappearing wild birds is global and complex, and the repercussions for people, wildlife, agriculture, and ecosystems are still playing out. Small, local actions like covering windows with stickers or revising landscaping practices may thus seem trivial. But studies of multiple structures, like one of graffiti-covered bus stops in Poland, tell us otherwise. When amplified by the thousands of buildings in the 400 plus parks in the U.S. National Park System, or by the more than 300 million people who visit these parks annually, even small actions become transformational.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chris Sheppard of the American Bird Conservancy for her guidance and expertise and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Bird Collision Team for their inspiration and for helping us tackle this important issue.

This article was originally published in the "Perspectives" section of Park Science magazine, Volume 38, Number 1, Summer 2024 (August 30, 2024) and on the National Park Service website.

The Authors:

Biological science technician Adam Reimer works at Zion National Park.

Dave Treviño is a wildlife biologist for the Washington Support Office of the National Park Service.

Sallie Hejl is a science advisor with the National Park Service's Intermountain Region.