Overview

About

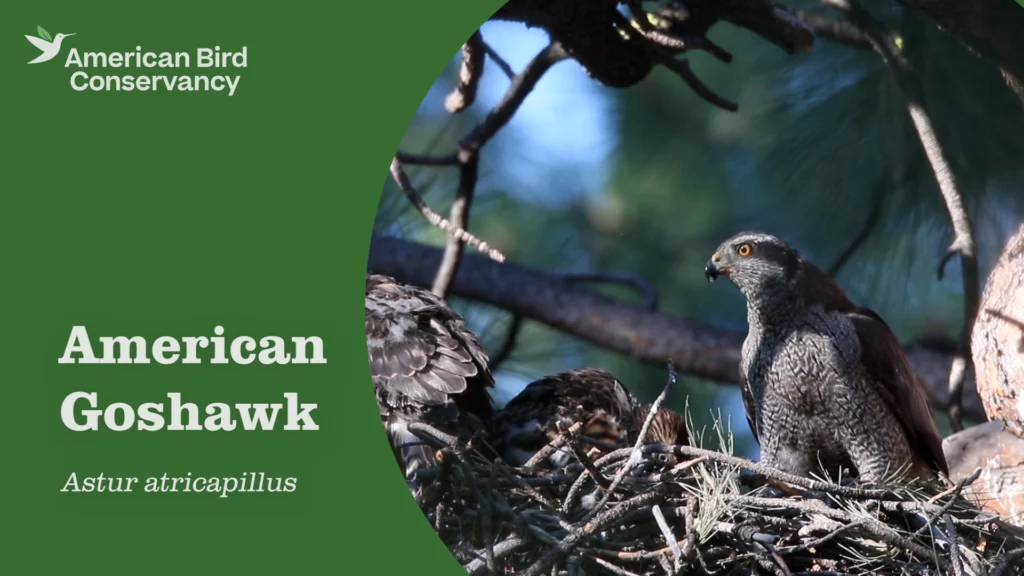

The formidable American Goshawk is the largest of North America’s “forest hawks,” a subset of raptors which includes the closely related, but smaller, Cooper’s and Sharp-shinned Hawks. It was split from the Northern Goshawk in 2024, along with its counterpart, the Eurasian Goshawk. Long-tailed with short, broad wings, this hawk is built for agile maneuvering while flying through dense undergrowth. As with other birds of prey, the female American Goshawk is larger than the male. An adult female “Gos” is almost as large and heavy as a Red-tailed Hawk!

This striking raptor has captured humans’ imaginations throughout the ages. Much like the Golden Eagle, the goshawk is revered across the world as a symbol of strength and power. Its hunting prowess made it a sought-after falconry bird throughout Europe and Asia. Japanese shoguns carried goshawks on their fists as status symbols, and the image of a goshawk once adorned the helmet of the mighty Attila the Hun!

In Europe, the closely related Eurasian Goshawk was once known as “the cook’s hawk” because it feeds on much of the same wild game that people prefer — grouse, ducks, rabbits, and hares — and was considered a valuable hunting partner. Unfortunately, many gamekeepers also saw goshawks as competition, which led to relentless (and illegal) persecution.

Threats

Birds around the world are declining, and many face urgent, acute threats. Even relatively stable species like the American Goshawk are vulnerable to the cumulative impacts of threats like habitat loss. The American Goshawk is considered a “management indicator” in many national forests because the species is quite sensitive to habitat loss and mismanagement, particularly during its nesting season. Goshawk pairs will abandon their territory and nests due to logging and other human activities, even those as low-impact as camping.

Habitat Loss

American Goshawks rely on mature forest to breed and favor larger trees for nesting. These forests and trees are also valuable for timber harvest, and unsustainable logging operations can degrade and fragment important nesting habitat.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

At ABC, we’re inspired by the wonder of birds like the fearsome American Goshawk, and we’re driven by our responsibility to find solutions to meet their greatest challenges. With science as our foundation, and with inclusion and partnership at the heart of all we do, we take bold action for birds and their habitats across the Americas.

Restoring HAbitat

Thoughtful forestry practices can help prevent American Goshawks from abandoning their nests and even improve nesting habitat. This more mindful approach can work in a variety of circumstances for other species, as seen in ABC’s work in the Northwoods region around the Great Lakes, which benefits the Golden-winged and Kirtland’s Warblers, Wood Thrush, American Woodcock, and many other local birds.

Bird Gallery

In adult plumage, an American Goshawk is unmistakable: blue-gray above and whitish-gray with faint, fine black barring below. It has fluffy white undertail coverts (contour feathers on the wings that cover other longer feathers) and a long, banded, dark gray tail. Its head has a dark gray to black cap with a contrasting white eyebrow, set off by blazing orange-red eyes. Juveniles are more of an identification challenge. Brown above and whitish with dark streaking below, they are often confused with juvenile Cooper’s Hawks. An immature goshawk has yellow eyes, which slowly darken to red as the bird ages.

Sounds

The American Goshawk is vocal during its breeding season, giving a loud, screaming kak-kak-kak call when defending its nest, communicating with its mate, and even while pursuing prey. Mated pairs stay in contact through calling, as visibility is usually limited within their forest territory. Fledgling goshawks make a persistent version of this call when begging for food.

Tayler Brooks, XC59174. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/59174.

Habitat

The American Goshawk is a bird of old forests, and can be found from sea level to subalpine woodlands up to 9,000 feet.

- Breeds in mature and old-growth forests, particularly coniferous or mixed hardwood-coniferous forests

- Prefers darker forest with a closed canopy

- Hunts in a range of habitats, from dense forest to open sagebrush steppe

Range & Region

Specific Area

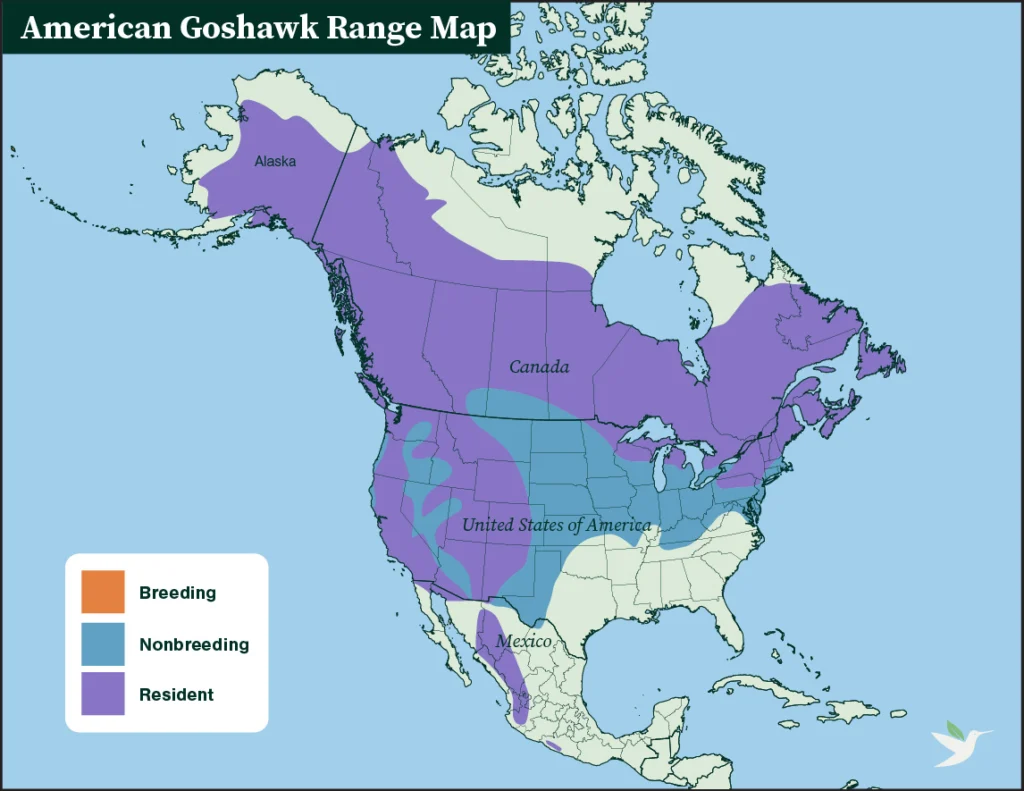

Canada, United States, and Mexico

Range Detail

The American Goshawk breeds across Canada and Alaska, and south through the Pacific Coast Ranges, Cascades, and Rocky Mountains as far as California, Arizona, and New Mexico. In the eastern United States, the goshawk breeds throughout Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, much of New York, and parts of Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. Some birds also breed in the Appalachian Mountains of Maryland and West Virginia. In Mexico, the American Goshawk breeds across the Sierra Madre. Outside of the breeding season, some birds will leave the breeding range and may be found across the northern and western United States.

Did you know?

Similar to Snowy Owls and many seed-eating birds, American Goshawks are known to have “irruption years” in which large numbers will leave the breeding range in search of food. This behavior is understood to be a result of food shortages in the species’ typical range, and occurs approximately every ten years. However, even during irruption years, American Goshawks typically avoid the southeast United States.

Life History

A stealthy hunter of undisturbed forest, the American Goshawk can be a challenge to see. They hunt by making short flights in dense cover and perching to scan for prey. They can be quite vocal at their nests, but have been known to attack humans who come too close! American Goshawks may also abandon nests if repeatedly disturbed, so if you hear a calling bird, it’s best not to approach it.

Diet

A top carnivore, American Goshawks take a variety of larger prey, including squirrels, hares, gamebirds, woodpeckers, corvids such as ravens and crows, and other large songbirds like the American Robin. Larger prey such as hares and jackrabbits may be up to twice the goshawk’s own weight!

Courtship

American Goshawk pairs are monogamous, but only come together during the breeding season. Breeding pairs perform a “sky dance,” in which males may first dive at or chase females through the canopy. Next, the pair will fly together low over the treetops in an undulating flight. Pairs will also copulate frequently — up to 500 times for a single clutch! This, as well as the sky dance, may help birds solidify their pair bond. The length of the pair bond is probably variable, but the data that do exist suggest that in some populations, pairs lasting at least 6 years are common.

Nesting

Nesting activity begins early, with the female beginning to build or repair her nest between February and April. A pair of goshawks will maintain up to eight alternate nests within their territory. Although they may reuse the same nest over successive years, the pair often selects an alternate nest each year. This “nest switching” may reduce exposure of their young to disease or harmful parasites. American Goshawks are also infamously aggressive nest defenders, killing nearby hawks and owls if deemed to be a threat.

Eggs & Young

Peak nesting activity occurs from April through June, when the female lays her clutch of two to four eggs. The female does most of the incubating, with the male occasionally taking a shift. The young hatch after approximately a month and a half, and the female tends them closely, with the male supplying food. The chicks fledge after another month, but remain close to the nest, depending on their parents for food for several months afterwards.