The sooty-gray Chimney Swift is best identified by its sleek silhouette, often compared to a "flying cigar." Twittering, gliding, and diving, often high in skies above cities and towns, Chimney Swifts are among the most aerial of all birds. Like another famous group of fliers — the hummingbirds — swifts have long wingtip bones that give them added maneuverability in flight.

The sooty-gray Chimney Swift is best identified by its sleek silhouette, often compared to a "flying cigar." Twittering, gliding, and diving, often high in skies above cities and towns, Chimney Swifts are among the most aerial of all birds. Like another famous group of fliers — the hummingbirds — swifts have long wingtip bones that give them added maneuverability in flight.

The family name, Apodidae, means "footless" in Greek. While Chimney Swifts (and the world's 100 or so other swift species) do in fact have feet, they're useful only for clinging to vertical surfaces. These birds eat, drink, mate, and even sleep on the wing.

A symbol of summertime across the eastern United States and into southeastern Canada, Chimney Swifts are most common in areas with an abundance of suitable chimneys for nesting and roosting. But even in those areas, swifts are becoming more scarce. Widespread pesticide use is a major culprit, since swifts and other aerial-insect-eating birds — including Purple Martin and Common Nighthawk — require healthy populations of flying insects to survive.

Chimney Swift in Free Fall

Habitat loss is also contributing to these declines. The sky itself is increasingly understood as habitat that needs conservation to minimize impacts on wildlife. What may appear to us as an empty sky is actually an ecosystem full of “aerial plankton” comprising airborne insects, spiders, and other minute lifeforms.

Pesticide use and agricultural intensification appear to may be reducing the amount of aerial food available for swifts, while tall buildings, wind turbines, and other structures increasingly occupy the airspace.

Chimney Swifts do most of their living in the air, but they must come to earth to breed. Historically, they nested in tree cavities, but lacking old trees with suitable holes for nesting, swifts long ago turned to chimneys. Today, deterioration of brick chimneys and homeowners' increasing use of chimney caps are limiting available nest sites.

Riddle of Bird Migration

Chimney Swifts are long-distance migrants and form large flocks as they prepare for their fall migration. At dusk, groups of up to 10,000 swifts may circle in a spectacular tornado-like display before finally funneling inside a large chimney to rest for the night.

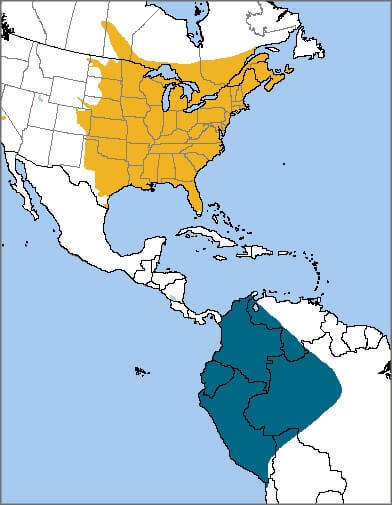

Researchers didn't know where Chimney Swifts spent the winter until 1944. In that year, banded birds were reported in Peru, solving “a centuries-old riddle of bird migration,” according to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service report. It's now known that Chimney Swifts also winter in Ecuador, Chile, and Brazil; very recently, a study found the species as a winter resident in Colombia.

Sign up for ABC's eNews to learn how you can help protect birds

The birds return to North America in flocks but divide into pairs soon after arriving on the breeding grounds. In a flight display signaling their pair-bond, male and female fly together, calling and gliding together in a downward curve.

Mated birds weave a loose nest of twigs inside a chimney or other vertical surface, using their sticky saliva to hold the nest in place. Male and female share in the work of caring for eggs and nestlings, sometimes with the help of an unmated bird.

Chimney Swift at nest by Bruno Kern

Help for Chimney Swifts

In spite of their aerial prowess, swifts are known victims of collisions with man-made structures. As our partner Nature Canada has found, Chimney Swifts fall victim to turbine blades. They are also found as victims of glass collisions; like other birds, they mistake reflections for open air.

ABC staff are working to minimize the impacts of turbines and glass collisions on birds. We're also undertaking research to better understand the roles of pesticides and agricultural intensification in population losses.

While there is much to learn, you can help Chimney Swifts by avoiding pesticides in your yard and garden, including neonicotinoids. “Neonics” are now are found in products from pet flea collars to lawn care products, and as our 2013 report revealed, they are toxic to birds and invertebrates even in small quantities. A single seed treated with neonics is enough to kill a songbird. Lesser amounts can emaciate the birds, impair reproduction, and disrupt migratory pathways.

You can also help this species by preserving existing chimneys or creating structures specifically for swift nesting. (See the Chimney Swift Nest Site Research Project for more information.) Check with local bird groups in your area to find out about opportunities to get involved in Chimney Swift monitoring, and report your sightings to eBird.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!