About the Nēnē (Hawaiian Goose)

The Nēnē is one of at least five species of geese that evolved on Hawaiʻi, including the Nēnē Nui (wood-walking goose) and the flightless Giant Hawaiʻi Goose. Today, the Nēnē is the only survivor, and one of the rarest goose species in the world. Based on fossil DNA, these Hawaiian geese are closely related to the Canada Goose, which was thought to have emigrated to the islands more than 500,000 years ago.

Another interesting group of waterfowl, the moa-nalos (lost fowl), once inhabited most of the Hawaiian Islands, but were quickly driven to extinction when humans arrived on the archipelago. These large, flightless, goose-like birds were actually more closely related to ducks such as the Mallard, had serrated bills with “teeth” like a Red-breasted Merganser, and were herbivores, grazing on ferns and other native vegetation.

The Nēnē is the official state bird of Hawaiʻi, and is mentioned in the Kumulipo (the Hawaiian creation chant) as being a guardian spirit of the land, symbolizing a link between the mountains and the coast because of their seasonal movements.

The Nēnē's genus name, Branta, is the Latin form of the Old Norse word brandgás, meaning “burnt goose” due to the dark feather coloring. Its species name sandvicensis refers to the Sandwich Islands, the name previously used by Europeans for what is known today as the Hawaiian Islands. This bird's Hawaiian name, Nēnē, refers to the sound of its soft honks.

An adult Nēnē is sepia to light brown, with darker feather edging giving it a barred appearance. It has a black face and crown, cream-colored cheeks, and a buff-colored neck with dark streaks. The strikingly furrowed-looking neck plumage is unique among waterfowl. The eyes, stubby beak, and feet are black.

Males and female Nēnē look alike, with males slightly larger. Nēnē have longer legs and less toe webbing than other geese, adaptations which help them walk on rough ground and over jagged lava flows.

Nēnē goslings are well-camouflaged by brownish-gray feathers and gain their adult plumage by five months of age.

Songs and Sounds

Nēnē calls resemble a Canada Goose's but are softer. Adult pairs and feeding flocks give low, murmuring nay-nay calls, the source of the species' Hawaiian name. These calls probably help maintain contact between mates and family members. Nēnē also give louder, shriller calls in alarm, aggression, during courtship, and when defending territory. Goslings give a variety of peeping calls.

Call:

Pair Calling:

Breeding and Feeding

The Nēnē is more terrestrial than other geese, and has developed adaptations to life on land that include long, strong legs, reduced webbing on its feet, and padded toes, all of which allow for more efficient walking and running over its sometimes-rugged terrain. Its upright stance allows it to reach high into the foliage as it browses.

Like Snow Geese and other waterfowl, Nēnē are herbivores. They forage mainly on land, grazing on a variety of grasses, grains, seeds, and leaves. On Hawaiʻi Island, Nēnē particularly favor the native ʻōhelo berry. This species also feeds on fruit and flowers.

Nēnē are monogamous and form lifelong pair bonds. The male courts a mate by walking ahead of her to show off his white undertail. After a female accepts him, the two engage in a “triumph ceremony” where the male aggressively repels potential rivals, then returns to his mate. They both call loudly while bobbing their heads.

This species has a long breeding season that runs from August to April.

The female Nēnē selects a nesting site under a bush or tree, where she digs a shallow scrape with her feet and lines it with vegetation. If the ground is too hard to dig, the female first builds a platform of vegetation, then hollows out her nest scrape atop that. She adds a finishing touch of soft down feathers plucked from her belly and breast as she begins to lay her eggs. Nēnē sometimes lay a second clutch if the first clutch or brood fails.

A female Nēnē lays a clutch of two to five large, relatively heavy eggs that she incubates for about a month. Nēnē have the longest incubation period of any goose, a trait shared by other waterfowl endemic to remote islands, where, in the absence of predators, birds were able to dedicate more resources to raising fewer, more precocial and well-developed young.

Her mate remains near the nest while she incubates, protecting her from potential predators. The downy goslings can follow their parents and feed themselves shortly after hatching, but they remain close to their parents until they are roughly one year old.

Region and Range

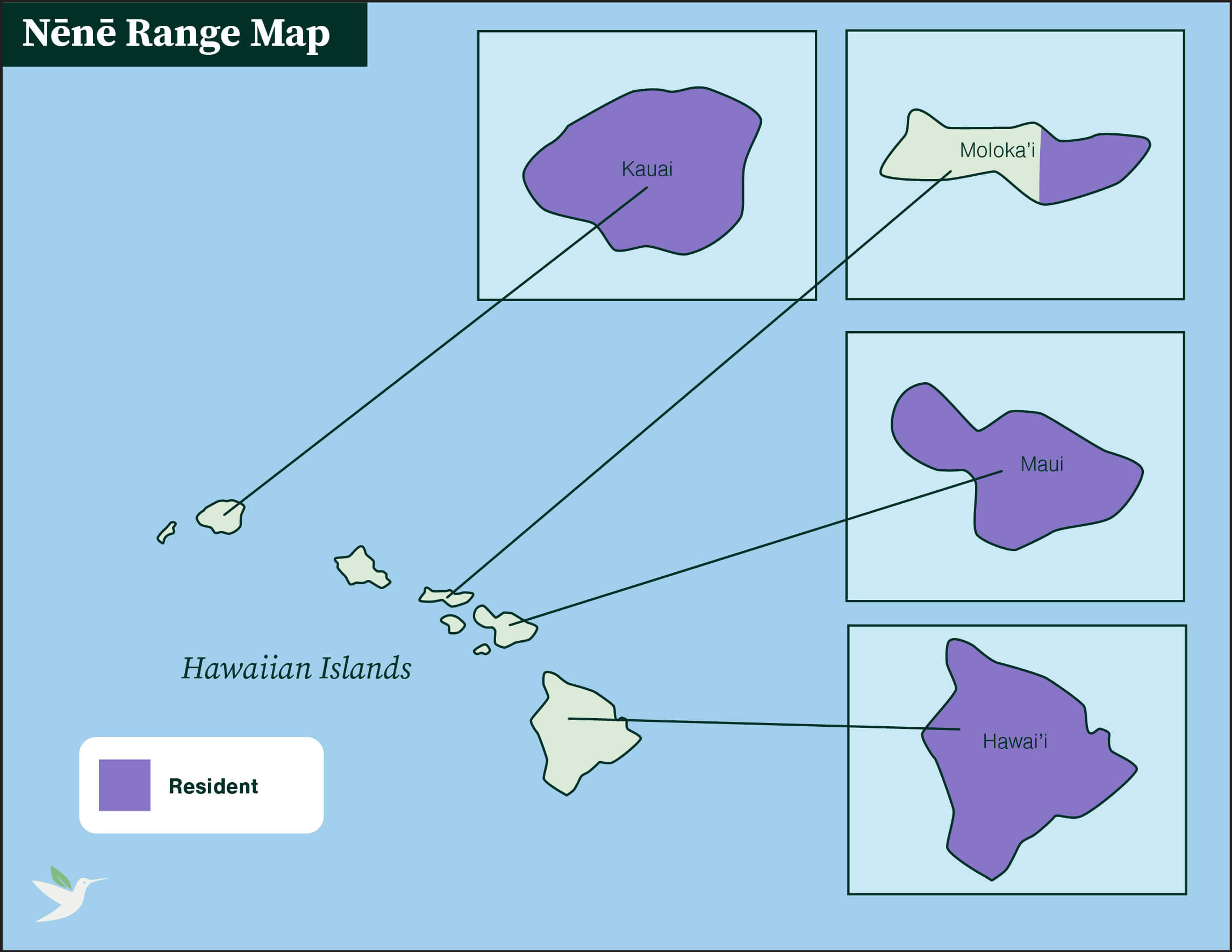

Nēnē once occurred in lowland habitats throughout the Hawaiian archipelago, but disappeared due to habitat alteration and predation. By the 1950s, only 30 Nēnē remained in the wild. Captive breeding and reintroduction efforts began in earnest in the 1950s, and populations of Nēnē can now be found on the islands of Oʻahu, Maui, Kauaʻi, Molokaʻi, and Hawaiʻi. Their distribution depends upon the locations of release sites for captive-bred birds, but tends to be concentrated at lower elevations. Populations on Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi Island, and Maui are now considered to be self-sustaining, although they continue to rely on predator control and habitat management.

Nēnē have somewhat small wings, another adaptation to their largely terrestrial lifestyle. While they are capable of flying between islands of the archipelago, they do not migrate longer distances away from the islands.

This native goose is not as closely tied to water sources as other waterfowl, and instead uses a variety of open habitats at differing altitudes in the breeding and nonbreeding seasons. Nēnē are very adaptable and can eat many introduced species of plants as well as native grasses and vegetation. They readily use human-altered habitats such as pastures and golf courses, and are attracted to vegetation resprouting in recently burned, grazed, or mowed areas.

Conservation

The alteration of the lowland habitats favored by the Nēnē accelerated in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the species was on the verge of extinction by the 1950s, with only about 30 birds remaining. Nēnē were once found on nearly all the main Hawaiian Islands, but habitat loss, predation by non-native animals, disease, and human disturbance decimated their populations.

Successful captive breeding and reintroduction programs have helped rescue the Nēnē from extinction. There are now approximately 3,800 individuals in the wild, and fewer than 100 in captivity worldwide. The Nēnē was reclassified from Endangered to Threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2019, and is considered Near Threatened by the IUCN Red List due to its small population size and the limited areas it inhabits. Conservation efforts are still needed to help Hawaiʻi's state bird get a stronger foothold.

Habitat loss through urban development, land conversion to agriculture, and the introduction of invasive plants poses an ongoing threat to Non populations. ABC collaborated with partners on the installation of predator-exclusion fencing at Kīlauea Point National Wildlife Refuge in Kauaʻi. Nēnē, along with other Hawaiian species such as Laysan Albatross (Mōlī), Newell's Shearwater (ʻAʻo), and Hawaiian Petrel (ʻUaʻu), are benefiting. ABC has also worked with partners to install predator-proof fencing elsewhere in Hawaiʻi, including on Molokaʻi.

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

Introduced predators such as rats, cats, dogs, mongooses, and pigs prey upon Nēnē adults, goslings, and eggs. Free-roaming cats can also transmit diseases such as toxoplasmosis. ABC encourages millions of people to keep their cats indoors or safely contained when outside — for their well-being, and for the birds'. We advocate for policies that promote responsible pet ownership and reduce the risks of free-roaming cats for wildlife and communities.

As Nēnē numbers have rebounded, the species has adapted to human landscapes. They can often be found in suburban areas crisscrossed by roads and fencing. Many are killed in collisions with vehicles, fences, and other human-made structures. Along with our partners, ABC supports efforts to reduce the risk of collisions with powerlines, streetlights, windows, and other human-made structures. We advocate for change, support policies that lead to lower collision fatalities, and take action in the courts to protect Hawaiʻi's endangered birds.

Nēnē suffer from lead poisoning and avian botulism. Herbicides and other pesticides applied to grassy areas such as lawns and golf courses also pose risks to Nēnē as they feed. ABC works with partners at the state and federal levels in the U.S. to call for the regulation or cancellation of the pesticides and toxins most harmful to birds. We develop innovative programs, like working directly with farmers to use neonicotinoid coating-free seeds. We are advancing research into pesticides' toll on birds and encouraging millions to pass on using harmful pesticides.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies have a huge impact on Hawai'i's birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Our Hawaiian partners frequently need help with habitat restoration and other projects benefiting birds. If you live in or will be visiting Hawai'i and would like to volunteer, check the following Facebook accounts for opportunities: Kaua'i Forest Bird Recovery Project, Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, and Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Project.

American Bird Conservancy and local partners are restoring forests, protecting critical habitat, and much more to save native Hawaiian birds. This is a monumental undertaking, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.