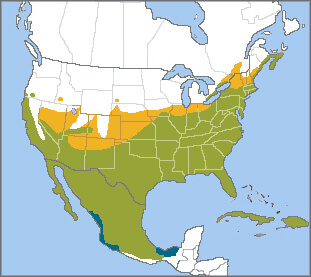

Northern Mockingbird range map by American Bird Conservancy

The Northern Mockingbird is well-known for its powers of mimicry. Nicknamed the "American Nightingale," this remarkable species has been recorded as learning the songs and calls of hundreds of other birds, as well as musical instruments, car alarms, and many other sounds. Its scientific name, which means "many-tongued mimic," reflects this vocal prowess.

John James Audubon paid tribute to the Northern Mockingbird's talents, remarking: “There is probably no bird in the world that possesses all the musical qualifications of this king of song, who has derived all from Nature's self."

Cultural Icon

The Northern Mockingbird is the state bird of five states — Arkansas, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas — reflecting its original, mainly southeastern distribution plus its tendency to nest close to houses. It's featured in literature, most famously in To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee's novel on race and the loss of innocence. Other southern writers such as Eudora Welty used the mockingbird as a motif in their works.

Native American culture casts the mockingbird in various myths as an intelligent teacher, diplomat, and peace-maker. The mockingbird is also popular in music, appearing in songs ranging from a traditional children's lullaby to a popular hit from the 1970s sung by James Taylor and Carly Simon, originally written and sung by Inez and Charlie Foxx in 1963. Recordings of the bird's song also feature on movie soundtracks and even pop up on occasion in the background of some songs.

Many Birds Should Be Flattered

They say mimicry is the greatest form of flattery. If so, no doubt the mockingbird would make many birds blush (if bird flattery and blushing were only possible). Sit nearby and listen to a singing “mocker” and you'll likely decipher many uncanny snippets emanating from the bird's bill — sounds of kingfishers, flickers, wrens, cardinals, and so on. Scientists speculate that this ability may make male mockingbirds more attractive to prospective mates. One study in Texas showed that male mockingbirds with the largest repertoires had the most resource-rich territories.

Despite its mania for mimicry, the Northern Mockingbird can usually be identified by voice, since each phrase of its complex song is usually clearly repeated three to five times before the bird goes on to the next. The complexity and variety of an individual bird's repertoire show its maturity and experience.

The Northern Mockingbird does have its own calls, including warbles, buzzes, chirps, and a distinctive “chewp” note (see “call” sound link below). These may be given alone or incorporated into its mimicked songs. Both males and females sing, but the male is a more active and persistent singer. During the breeding season, a male mockingbird will often continue singing through the night, occasionally leaping into the air with exuberance, and unpaired males even sing 24 hours a day.

Listen to the Northern Mockingbird's songs and calls here:

(Audio: Northern Mockingbird song by Mike Nelson, XC57040. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/57040. Northern Mockingbird call by Paul Marvin, XC161347. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/161347 )

Song from the South

Originally a species strongly identified with the South, during the 20th century, the Northern Mockingbird expanded its range to the Canadian border, helped along by the introduction of invasive exotic shrubs such as the Multiflora Rose, which provides food and shelter favored by this species. Today, the Northern Mockingbird is found in more than half of the continental United States and in far-eastern Canada, in much of Mexico, and also in the Bahamas and on many Caribbean islands. It is also now found in Hawai'i, where it was introduced in the 1920s. Although it's mainly a permanent resident, northernmost North American populations may move south during harsh winters.

The Northern Mockingbird belongs to the family Mimidae, which also includes thrashers, such as the Sage and Bendire's Thrashers, and catbirds. From southern Mexico into South America, the species is replaced by the closely related Tropical Mockingbird, with which it occasionally hybridizes.

Flashy Feeder

An omnivore, the Northern Mockingbird splits its diet between invertebrates and fruits. Like many other birds, including the American Robin and Eastern Bluebird, it changes its menu with the seasons, feeding mainly on insects such as beetles, grasshoppers, caterpillars, ants, and wasps during the spring and summer, switching to fruits and berries in the fall and winter. It readily visits backyard bird feeders for fruit, suet, and sometimes seed.

The mockingbird can be seen foraging on lawns, fields, or other open ground, where it hops and runs along the ground after prey. It also adroitly pursues insects in mid-air, with quick twists and turns. While foraging, the Northern Mockingbird sometimes quickly snaps its wings, flashing their white patches, a move that may startle potential prey into movement. This "wing flash" may also be related to territorial and/or defensive behaviors.

Northern Mockingbird with holly berry. Photo by David Byron Keener/Shutterstock

Fearless Nest Defender

When it comes to courtship and nesting, the Northern Mockingbird is just as conspicuous as in other aspects of its life. A male first establishes a territory through incessant song, then woos a female with displays that include chases, showing off potential nest sites, and flight displays. The male may even begin multiple nests to entice a female. During its flight display, the male mockingbird launches from a high perch while singing, then parachutes slowly back down, flashing its white wing patches.

This is generally a monogamous species, and pairs form long-term bonds, sometimes mating for life. Once the female selects her nest site (or a male's partially built nest), she finishes the cup-shaped collection of twigs and other vegetation, lining it with finer grasses and human artifacts such as paper, foil, cotton, twine, and plastic. Pairs will raise two to four broods a year, each starting with an average of four eggs. A new nest is built each time, and the male often begins building a new nest as the female raises the prior nest's brood.

The mockingbird is fiercely territorial, attacking and driving off intruders many times its size, including hawks, house pets, and even people.

Keeping the Northern Mockingbird Singing

Due to its singing skills, the Northern Mockingbird was once a popular cagebird. During the 19th century, its populations reached an all-time low along the East Coast, as many were captured as pets. It also suffered depredations from egg collecting, another once-popular hobby. Thanks to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, these factors are no longer threats.

This widespread species of suburbs and cities still faces a number of human-caused threats, including collisions with buildings, poisoning by pesticides, and predation by outdoor cats. Partners in Flight has documented a 19-percent drop in mockingbird populations in the U.S. and Canada between 1970 and 2014.

ABC has a number of programs in place to reduce threats to the Northern Mockingbird and other birds, including our Cats Indoors program, which encourages pet owners to keep cats and birds safe, and our Glass Collisions program. Explore solutions to keep birds from hitting windows.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!