About the Northern Waterthrush

Along with its cousin the Louisiana Waterthrush and the forest-living Ovenbird, the Northern Waterthrush is one of the only warblers colored like a sparrow or thrush, with a plain brown back and dark-streaked white underparts. It is also one of the few warblers to forage on the ground, patrolling the water's edge. As it strolls the mud, its backside constantly pumping up and down, it's easy to see why people might have a hard time believing this bird is related to the gaudy Yellow Warbler or Prothonotary Warbler.

Northern and Louisiana Waterthrushes challenge birders' identification skills whenever both of these look-alike species occur in the same area. They certainly confused early naturalists. Apparently, though, the birds clearly recognize their differences: Even when they breed in the same areas, the two species do not compete with each other, nor do they hybridize.

Similar Yet Separate

When they do breed in the same area, territorial Northern Waterthrushes do not chase Louisiana Waterthrushes, as they do others of their own species. Studies of these birds seem to indicate that they may not compete with each other in part because they've evolved to forage differently and seek out somewhat different prey. They also choose different nesting sites: For example, Northern Waterthrushes tend to favor areas with more ferns, conifers, alders, mosses, and different shrub cover than selected by Louisiana Waterthrushes.

Songs and Sounds

The Northern Waterthrush belts out a distinctive and far-carrying series of gravelly, repeated notes at three different pitches, like: "CHIT CHIT Durr Durr Weer." In contrast, the Louisiana Waterthrush has a sweeter, down-sliding then rising song.

Listen to both songs here:

Northern Waterthrush song:

Louisiana Waterthrush song:

Breeding and Feeding

Clumps, Stumps, and Root Jumbles

Northern Waterthrushes usually nest low in locales where lush and jumbled elements provide camouflage near the water's edge. For example, nests are often placed among roots of fallen trees or among fern clumps, beneath stream- or riverbanks, or in holes in rotting stumps. The nest is usually hidden from view by overhanging vegetation.

The female builds her open-cup nest out of materials including leaf fragments, small twigs, pine needles, thin bark strips, and moss. The cup is lined with finer materials such as grass bits, pine needles, rootlets, and soft animal hair.

The female Northern Waterthrush lays four to five eggs, which she alone incubates for almost two weeks. Both parents feed the growing young, which usually leave the nest about ten days after hatching.

The Northern Waterthrush diligently patrols the water's edge, often flinging aside wet leaves as it forages. It will also wade into the shallows in pursuit of prey, which includes aquatic beetles, damselflies and dragonflies, flies, stoneflies, mayflies, and mosquitoes. Caterpillars are also important food. Other invertebrate prey includes spiders, snails, small slugs, and tiny clams and crustaceans (on migration stopover and wintering grounds). Occasionally, small vertebrates wind up on the menu as well, including minnows and a tiny salamander or two.

Region and Range

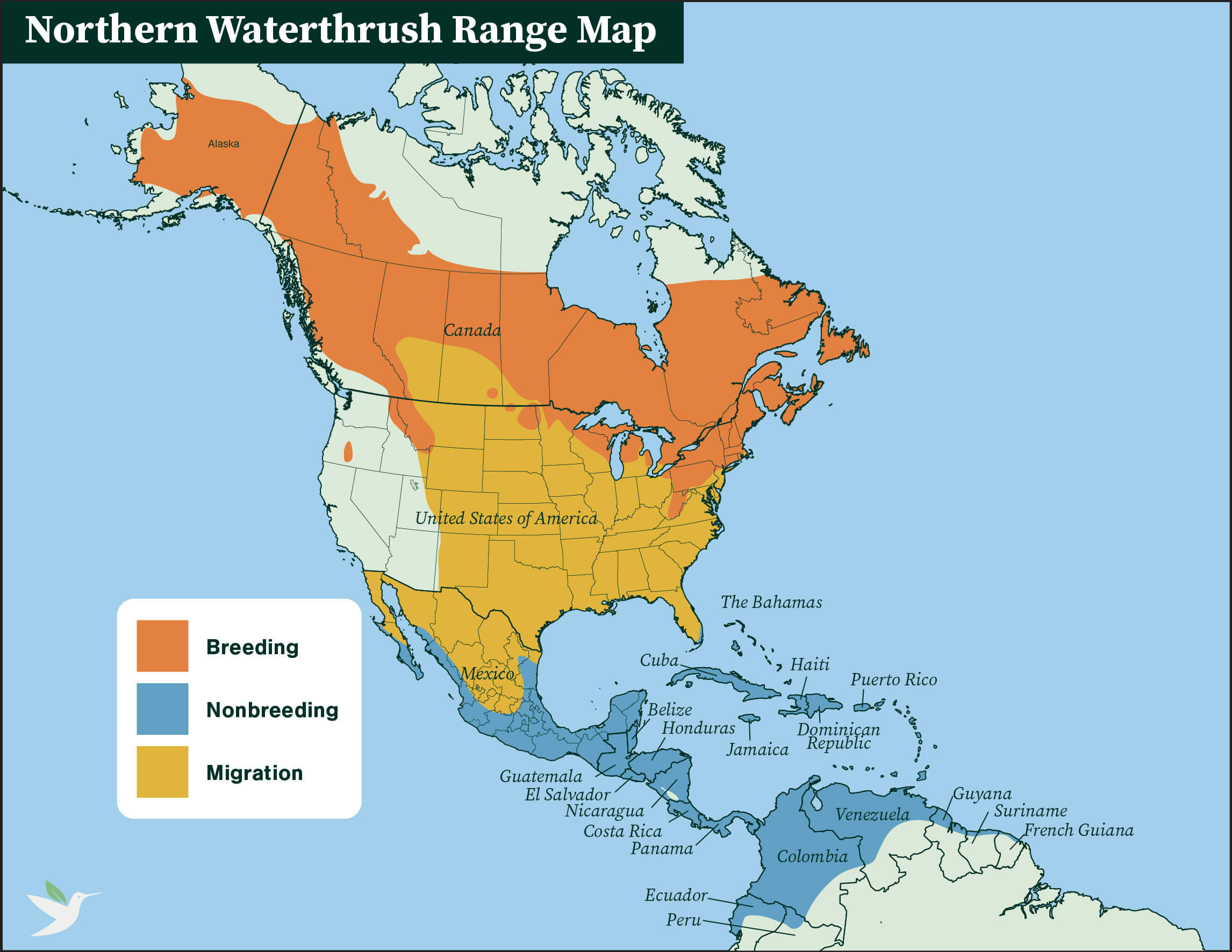

The Northern Waterthrush nests in northern bogs and swamps, habitat shared by bird species such as the Wilson's Snipe, Ruffed Grouse, Black-backed Woodpecker, and Purple Finch. It may also nest along thickly vegetated streambanks and shorelines flanking rivers and lakes. It breeds across the lower two-thirds of Canada and Alaska, south into many of the northernmost lower 48 U.S. states. A few isolated populations occur in Oregon and elsewhere. This species' breeding range also dips south in the Appalachian Mountains, reaching into parts of West Virginia and Virginia.

During migration, the Northern Waterthrush sometimes turns up in backyards or urban parks with water features or standing puddles. The species winters across a broad range, from South Florida, southern Louisiana, and South Texas to northern South America (to northern Ecuador, with some even reaching Peru). The Northern Waterthrush is also a common winter visitor in Bermuda and across the West Indies. Habitats used during migration and winter include mangrove forests and shaded farms, gardens, and tropical forest in lowlands and lower foothills, usually near streams or other water sources.

Conservation

Despite Dangers, Doing Well

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

Like many Neotropical migrants, the Northern Waterthrush faces a mix of threats. These include habitat loss (especially in wintering and migratory stopover areas), pollution of wetlands, collisions with glass and tall structures, and free-ranging cats.

With a large range and ability to nest and feed in a variety of damp habitats, the Northern Waterthrush seems to be doing much better than many of its declining brethren. According to Partners in Flight, the species has been undergoing a large increase in population. One 2018 study estimated an 18-percent increase during the prior decade. The reasons for this jump are not well understood, nor is it easy to predict how long the increase will continue, especially given pressures on wintering habitats including mangrove forests.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on migratory birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Living a bird-friendly life can have an immediate impact on migratory birds in the United States. Doing so can be as easy as adding native plants to your garden, avoiding pesticides, and keeping cats indoors. To learn more, visit our Bird-Friendly Life page.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on more than 8.5 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. That's not all: With the help of international partners, we've established a network of more than 100 areas of priority bird habitat across the Americas, helping to ensure that birds' needs are met during all stages of their lifecycles. These are monumental undertakings, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.