Saving Red Gold: The International Effort to Rescue Red Siskins

A tale of two songbirds, one wild and vanishing, the other domesticated. Will this story end happily in one of the world's most challenged countries?

On a dreary winter morning, three of us from American Bird Conservancy (ABC) escape the Nation's Capital sprawl, driving west to the Blue Ridge Mountains. Our goal: to see one of the Americas' most eye-popping and fast-vanishing birds. After two hours, we reach our target destination, pulling into the 3,200-acre Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) and up to an unassuming beige building called the Small Animal Facility. When we leave the car, we're neither wearing parkas nor carrying binoculars. This is no birding stakeout, after all, but a bird encounter of a different kind.

SCBI is a rural redoubt geared to recovering imperiled species. Black-footed Ferrets, Guam Kingfishers and Rails, and members of southeastern Canada's rare Loggerhead Shrike population all live in the building we've entered. But there's also another resident, a species ABC, the Smithsonian Institution, Venezuelan partner and nongovernmental organization Provita, and others work together to save. Looking like a goldfinch cloaked in cardinal plumage, the bird we seek is, in fact, called Cardenalito in South America.

Soon, 17 Red Siskins — half the North American zoo population — zip before us, the males breathtaking blazing-red with black heads and wings, and the females gray, patched with red. We hear rich, warbling songs and inflected, almost questioning calls that remind us of local goldfinches. Mostly hidden within a purple-flowering plant hung from the ceiling, a female sits on a tightly woven nest.

Male Red Siskin. Photo by Gerhard Hoffman/Alamy Stock Photo

Keeper Erica Royer shows us a used nest unlike any ever found in the Red Siskin's northern South American range. It consists mostly of burlap and coconut fiber and string. But the soft layer inside, where jellybean-sized, mostly white eggs once sat, includes contributions from other exotic wildlife living at the facility: “The birds here line their nests with materials we provide,” says Royer, “and that includes bison fur, Cheetah fur, and Scimitar-horned Oryx and Dama Gazelle hair.”

We learn that these pampered siskins won't remain here for long. Over the past several years, SCBI keepers and researchers have honed the most effective strategies for breeding these birds, tweaking housing and dietary arrangements, monitoring behaviors and matches — so that these husbandry “secrets” will help other zoos carry the torch. Through careful tracking and coordination, these North American institutions aim to create a Species Survival Plan yielding a genetically rich, sustainable zoo-network population. A similar effort is underway in Europe, the part of the world where the South American siskin's troubles began.

Gaudiness and Greed

Under normal circumstances, Red Siskins wouldn't be rare. Like many goldfinch and siskin species, they are habitat generalists, frequenting patchworks of semi-humid forest and edge, fields, and farms, including shade-coffee plantations. Flocks often wander nomadically depending upon the season, divining the best spots to find a bounty of seeds and berries.

The Red Siskin's eye-catching color proved to be its downfall. As the Spanish colonized Venezuela in the 1500s, returning ships brought back many “newly found” creatures, including this fiery-red finch. Imperial powers kept many secrets from each other. Apparently, Cardenalito was one: Almost three centuries passed before the species was recognized by science and began dazzling the rest of Europe.

By the late 1800s, Red Siskins were being imported in large numbers, not only as pets but also to feed the feather trade, with dead birds' plumage providing a splash of cherry-red to hats and other accessories. But the biggest wave of siskin capture was yet to come, inextricably tied to a familiar songbird hailing from windswept islands off the North African coast.

Captive-bred Red Siskin at the Smithsonian facility. Photo by Chris Crowe

Like a Canary in a…

The Island Canary was on Europeans' radar long before Red Siskins appeared. Early in the Age of Exploration, in the late 1300s and early 1400s, Spanish and Portuguese ships brought back intriguing streaky, greenish-yellow songbirds from the Canary Islands. Although pretty, these birds did not look much different from the closely related European Serin, common on the mainland. The imported birds, however, wowed people with their rich, sustained songs. By the 1500s, canaries were sold across Western Europe. And through careful matchmaking, breeders began selling more colorful individuals. All yellow canaries debuted by the mid-1600s, and many fancy breeds followed.

“By the 1870s,” wrote Tim Birkhead in his 2003 book The Red Canary, “songbirds could be heard and seen in virtually every home in Europe.” Canaries were especially prized in these years before radio and television, their trilling and deep warbling providing comforting background music.

Of course, canaries had another important use. Calling an environmentally sensitive species a “canary in a coal mine” is now a tired metaphor, but these songbirds really did join miners as they were lowered down impossibly long, pitch-black mine shafts. There, canaries provided an air-quality alert system, the sensitive birds dropping dead when toxic fumes crept into a shaft.

When Canary Met Siskin

These days, consumers crave the groundbreaking and exciting, in cars, cellphones, fashion, and running shoes. The same spirit prevailed in the centuries-old cagebird trade around the time of World War One, when a hot new idea surfaced: the creation of a red canary. This endeavor proved to be quite a challenge, but like hard-core birders, aviculturists are a highly competitive and persistent lot. Starting in the 1920s, orange breeds appeared. But eye-popping red canaries remained elusive.

In his book, Birkhead describes how in 1924, after seeing a Red Siskin in an aviary and hearing that a few aviculturists had dabbled in matching the siskin and canary, German geneticist Hans Duncker hatched a plan that went a concerted step beyond. He had spent years tinkering with canary genetics and now wanted to experiment with two species, producing a canary that inherited the siskin's striking scarlet plumage color. “His idea was to combine the genetic material of two distinct species to create a new one — a transgenic canary,” wrote Birkhead. “This was the first attempt to create a genetically modified animal, the first bit of animal gene technology.”

Given no other alternatives, birds of the two species can interbreed and produce viable young. Within two years, persistent Duncker and his colleague Karl Reich had tried their first Red Siskin x yellow canary crosses. The birds they produced, though, were at best orange. Competitive aviculturists kept reaching for red. “The popularity of coloured canary projects in North America and Europe meant that from the 1940s, huge numbers of Red Siskins were taken from their native Venezuela to fuel the bird breeders' fantasies,” wrote Birkhead.

Yellow canary by Eric Isselee, Shutterstock; Red Siskin pair by yantzepg; red-factor canary by Eric Isselee, Shutterstock

“Many of the siskins didn't survive the transatlantic journey, and in a few decades the population plummeted,” says Brian Coyle, the Smithsonian's Conservation Commons Program Manager. Coyle began working on Red Siskin conservation at the Smithsonian in 2013 and was main coordinator for the international partnership called the Red Siskin Initiative (RSI), of which ABC is part. He remains a lead member. “By the early 1950s, the Red Siskin was the first species in Venezuela to receive endangered species status.”

Around this time, aviculturists realized that the only way to attain a reddish canary was to feed orange, or “red-factor,” canaries — the result of crossing then back-crossing Red Siskins and canaries — a diet including carotenoid supplements. Birds do not produce carotenoids themselves, but acquire them through diet. Such diet-induced color enhancement occurs in many wild birds, including flamingos, House Finches, and Northern Cardinals.

Red canaries finally appeared in 1964, when orange canaries were fed a supplement called Carophyll that is used to pigment factory-raised chickens' egg yolks. So, in the end, the red canary was a product both of genetics and diet.

A Tattered Range

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) now lists the Red Siskin as Endangered, with an estimated remaining wild population ranging from 1,500 to 7,000 adults.

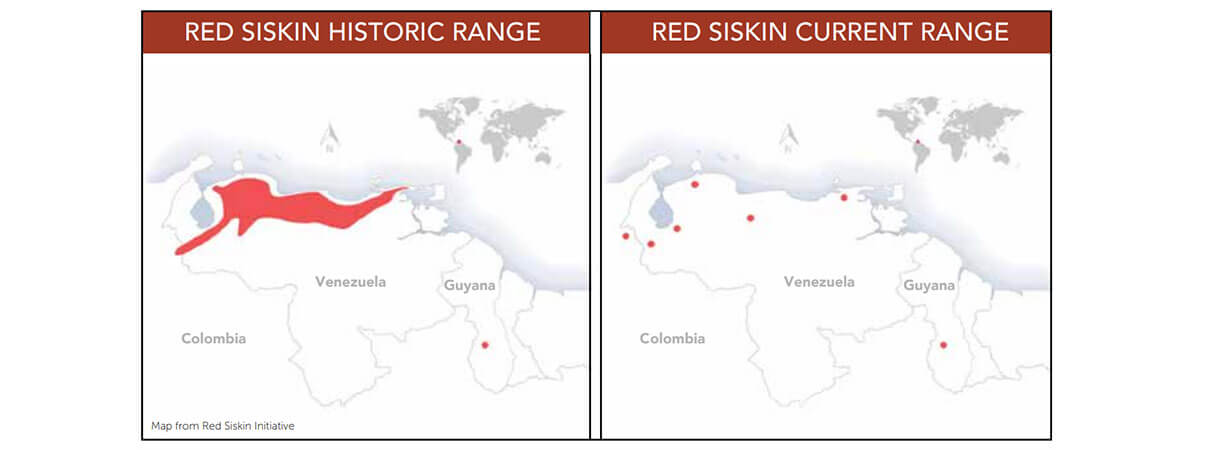

Red Siskins now occur in just seven known pockets of habitat, after once being a common bird across northern Venezuela, west to the Colombian border. The species is known from the Caribbean as well, with likely recent reports from Puerto Rico. And in Guyana, a population is located far from other known sites, near the Brazilian border.

Since the species was found in Guyana in 2000, ABC and other groups have supported its conservation and petitioned the government to have it protected. As in Venezuela, it is now illegal to capture or otherwise harm siskins in Guyana. (In the U.S., Red Siskins receive protection under the Endangered Species Act and cannot be legally bought or sold without a special “captive-bred wildlife” permit issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.)

Everywhere they remain, however, wild Red Siskins are sought by poachers, not so much for the canary trade anymore, but because these birds are pretty and rare and thus valuable, in the U.S. fetching up to $600 on the black market. Ending the global trade in wild birds would help the siskin.

Red Siskin range map. Map from Red Siskin Initiative

Red Dawn

Although they are now rare, there's hope for a Red Siskin revival. Partnerships, ongoing conservation work, and community involvement now play vital roles in the species' future. And much of the work, including a new breeding facility (see "Venezuela's Red Bird Renaissance" below), is now being carried out in Venezuela, always the core of this species' range.

Despite day-to-day challenges, Provita is making headway to save some of Venezuela's rare wildlife, and the Red Siskin tops the list, in part because it features prominently in the country's culture. The Cardenalito graces the country's currency and pops up in songs, poetry, and art. Yet few young Venezuelans have ever seen one in the wild. Hopefully that soon will change.

Once the captive-bred population builds, the plan is to release birds on farms and in natural areas in northern Venezuela, including in two areas where the Red Siskin Initiative is working with farmers: the Piedra de Cachimbo and La Florida.

These agricultural communities sit nestled between Henri Pittier and Macarao National Parks in north-central Venezuela. Bird-friendly agriculture there would help build a wildlife habitat corridor between these protected areas, benefiting not only siskins but more than 70 migratory bird species, including Cerulean Warblers, Northern Waterthrushes, and Olive-sided Flycatchers.

The targeted farms now cover 400 acres, but the area will be expanded in coming years.

CLICK TO READ MORE: Venezuela's Red Bird Renaissance

“We've been really pleased at the level of interest that other AZA facilities and national and international partners have expressed in this species,” says Dr. Kathryn Rodriguez Clark, a population ecologist for the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Red Siskin Initiative co-founder.

In Venezuela, the Red Siskin Initiative (RSI) team, led by Miguel Arvelo as coordinator, recently inaugurated an offsite breeding facility. At the Red Siskin Conservation Center (RSSC), housed within the private Leslie Pantin Zoo in Turmero, a founder population is being built that hopefully will yield birds for reintroduction into the wild. “We have created essential infrastructure to rescue, rehabilitate, raise, and one day reintroduce this species in a sustainable way,” says Arvelo. “This center will house a Red Siskin population that helps to ensure against extinction.”

Built using an AZA grant, the center received confiscated Red Siskins and also some donated by Venezuelan cagebird breeders. “Working with breeders in Venezuela is another part of RSI's educational and outreach efforts, and is creating a conservation mindset,” says the Smithsonian's Brian Coyle. “We're working with breeders in Venezuela. Provita is reaching out and creating an alliance between conservationists and aviculturists. Breeders have responded very positively. They feel a strong sense of responsibility to help recover this beloved species in the wild.”

— Howard Youth

Linking Siskins with Better Farm Yields

“We know that reserves are important for conservation, but it's not enough,” says Andrés Anchondo, Conservation Specialist with ABC's Migratory Bird Program. Anchondo works with Provita on projects that build capacity in shade-grown coffee and other agricultural communities in Venezuela. “We work on a variety of habitats, and collaborating with communities is key, especially for

Red Siskins and migratory birds, particularly those that use a wide range of landscapes.”

ABC and partners also work with farmers to help them get their harvests certified. When rollercoastering coffee prices plunged, many Venezuelan shade-coffee farms were cleared for other crops. RSI partners have been working with remaining shade-coffee growers to get USDA Organic, the Organic Standard of the European Economic Community, and Smithsonian Bird-Friendly® certifications, which yield a higher price for their crop and enable them to export it to interested overseas buyers.

So far, 39 farms are certified USDA Organic, including 13 that also have Smithsonian Bird-Friendly® certification, which requires, among other things, the use of ten or more native shade tree and shrub species; more than 40-percent foliage cover; preservation of leaf litter and groundcover plants; and, when possible, living fences.

The partners also help farmers excel. “We have been providing them with technical assistance with farming practices, including how to produce organic fertilizers, and helping to build strong relationships with farmers while building capacity,” says Anchondo. “Provita helped create a cooperative and helped farms get certified organic and Smithsonian coffee certification.”

A field technician checking shade-grown coffee at a Venezuelan plantation. Photo by Gerhard Hoffman/Alamy Stock Photo

Smithsonian's Brian Coyle points out how involving farmers in conservation work makes a huge difference to the birds. “Wild siskins forage and nest in shade-coffee farms in Venezuela. This gives us the opportunity to release birds in a controlled location that keeps them safe from trappers, and where farmers can help with monitoring.

“Not only are we helping farmers with their livelihoods, we are showing how conservation can benefit them economically, and how they can be ambassadors for protection of endangered species in the country and the world,” Coyle adds.

Shortly after bidding the siskins adieu and stepping out of SCBI's Small Animal Facility, we hear American Goldfinches overhead. It's hard to imagine a bird as ubiquitous as a goldfinch being absent from this landscape. But that's exactly what's happened to Red Siskins in Venezuela. With so many encouraging conservation efforts underway, Red Siskin fans have some strong reasons for hope. With determination, partnership, and focus, it's quite possible that in the years ahead, we'll all be able to rejoice in the return of Cardenalito.

ABC thanks Environment and Climate Change Canada for its support of our work with Provita and the Northern Venezuela BirdScape.

| Howard Youth is ABC's Senior Writer/Editor, and is the author of Field Guide to the Natural World of Washington, D.C. |