In Virginia's Piedmont Grasslands: a Firmer Foothold for Declining Birds

The Mid-Atlantic region is known for its symbolic Blue Ridge Mountains, bays and marshes, and flourishing deciduous forests. While these important habitats harbor some of North America's most admired bird species, there's one important ecosystem that's often overlooked for bird conservation in these human-dominated landscapes — eastern grasslands.

The majority of eastern grasslands are on privately owned land under some form of agricultural management. They provide critical habitat for some of our nation's most sharply declining species: For example, the Eastern Meadowlark, which has declined by more than 70 percent since the 1970s, relies upon private lands for 97 percent of its remaining habitat in the U.S. To conserve this iconic bird, it is essential for landowners, scientists, and conservation managers to collaborate on effective management of these landscapes. What's happening in Virginia's Piedmont grasslands provides a hopeful example for how this can work elsewhere.

Northern Virginia farmers are helping to bring back grassland birds by maintaining meadows and timing hay harvests to accommodate nesting. Photo by Amy Johnson

Rolling Out a Green Carpet for Grassland Birds

Nestled among the bucolic rolling hills just west of Washington, D.C., and coincidentally surrounding the home office of ABC in The Plains, Virginia, there exists a community of farmers, land managers, and homeowners who are collaborating with a team of Smithsonian scientists to help bring back the birds of Piedmont grasslands.

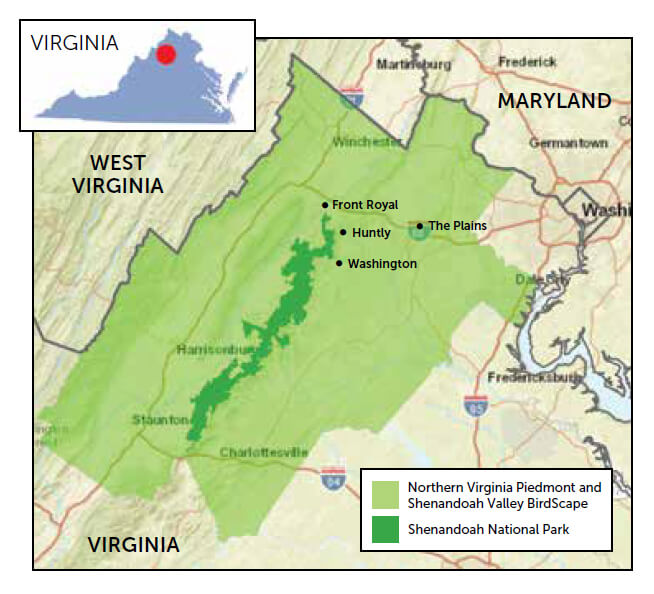

The new Northern Virginia Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley BirdScape is located just outside of Washington, D.C., and encompasses areas surrounding Shenandoah National Park (shown in dark green).

Virginia Working Landscapes (VWL), a program of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute in Front Royal, collaborates with landowners, community scientists, universities, and other local partners to study the region's biodiversity on private lands. Since 2010, the VWL team has surveyed more than 150 properties across 16 counties in Northern Virginia's Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley. Together, these properties cover more than 80,000 acres, from hilly Loudoun County to the mountains bordering Augusta County.

With much of this region under private ownership, it is an ideal landscape to gain a better understanding of how the actions of landowners influence the wildlife with which we share our grasslands. These properties now also form an integral part of a newly declared conservation zone, or BirdScape, established this year by ABC, VWL, and partners at the Piedmont Environmental Council (PEC). It's called the Northern Virginia Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley BirdScape.

A BirdScape defines a focal area for conservation efforts, where partners can work together to address the issues affecting declining bird populations. Throughout the year, Virginia's Piedmont grasslands are frequented by more than 100 bird species, including breeding and wintering grassland specialists that are in steep decline. Efforts are now underway to help study, protect, and restore some of the grasslands within the new BirdScape, which is only the second one east of the Appalachians and the first to focus on the Virginia Piedmont's working grasslands.

Grass of the Past

From pre-European times up to the mid-1700s, lands between the Atlantic Ocean and Appalachian Mountains included some extensive and important grasslands and savannas. Many of these were maintained by frequent burning, either by Native Americans or natural, lightning-started fires, but they also occurred on shallow soils, balds, and barrens. The Virginia Piedmont grasslands, like other prairies, were home to a great many native plants, including endemic species, and even to large animals such as Elk and American Bison. But they were also breeding and wintering areas for many bird species, including some now mostly gone from the area.

European settlers in the 1600s and early 1700s plowed the grasslands and suppressed fires that had maintained the region's prairies. By the early 1900s, only small patches of this habitat remained. Then, when agriculture began to shift to the Great Plains in the late 1800s and early 1900s, many farms were abandoned in the Piedmont.

But the prairies did not return. Today, few people living where they once stood have any idea they existed. Over the decades, properties not maintained in agriculture grew to tall, dark woodlands. Meanwhile, those utilized for grazing were mostly converted to nonnative grasses, robust introduced plants that provided forage for cattle, sheep, and horses. While some grassland bird species have adapted to these nonnative grasslands, the intensity with which they have been managed, combined with the loss of important native grasses and forbs, have contributed to the significant bird population declines we see today.

For example, Northern Bobwhites, Eastern Meadowlarks, and Grasshopper Sparrows have greatly declined in the northern Piedmont; Bobolinks and Savannah Sparrows have become rare breeders south of Pennsylvania; and some, like the Henslow's Sparrow and the Loggerhead Shrike, a predatory songbird, are now only rare visitors. The ecological impacts of these losses could be devastating. As we lose diversity of species, we lose resiliency — making our ecosystems less adaptable to change.

Bobolink nesting, from egg to fledgling. Photos by Bernadette Rigley

Returning What Was Lost

In recent years, there has been growing interest in recovering some of what was lost in the Piedmont, with landowners trying both to rebuild native grasslands and regenerate existing working grasslands, while ensuring indefinite land protection through conservation easement programs. The new BirdScape will help to focus these efforts and provide a framework for bird conservation efforts.

Conservation is already at the forefront of many land management decisions in the region. For example, land protected by conservation easements in PEC's nine-county service area accounts for nearly 20 percent of the total land area, making this particular region “one of the best examples of private land conservation in the nation,” according to Michael Kane, PEC's Director of Conservation and a key partner on the new BirdScape. This achievement reflects “a decades-long partnership between landowners and conservation organizations to preserve — for the benefit of the public at large — the natural resources, rural economy, history, and beauty of the Virginia Piedmont,” he adds.

Conservation easements will play an important role in establishing the new BirdScape, as permanent protection of farmland will help connect and preserve critical grassland habitat in perpetuity. In addition, the BirdScape partners will work together to study, document, and promote grassland management practices that benefit bird conservation, including rotational grazing, bird-friendly mowing, riparian buffers, and native grass and wildflower restorations.

Common Yellowthroat in a native wildflower meadow at The Farm at Sunnyside in Washington, VA. Photo by Amy Johnson

Sowing the Seeds of Crops and Conservation

A prime example of how farms can make a huge difference for the region's grassland birds sits in the heart of Washington, Virginia, where rich wildlife habitat is nurtured alongside rows of highly sought-after organic produce. The Farm at Sunnyside, owned by Nick and Gardiner Lapham, has converted nearly 40 acres of farmland into diverse native meadows supporting populations of Northern Bobwhites, Indigo Buntings, and Field Sparrows, to name a few. “Agriculturally driven land use change and management is the single greatest cause of biodiversity loss globally,” says Nick, a former member of ABC's Board of Directors. “We want to be part of the effort to change that.”

Research conducted by VWL and their team of community scientists has shown that meadows like these support significantly higher densities of declining shrubland bird species such as Prairie Warblers, Yellow-breasted Chats, and Common Yellowthroats, compared with traditional hay fields and pastures.

“It's been tremendously gratifying to see how habitat enhancements such as planting native meadows have, over a relatively short time period, resulted in expanded bird populations,” says Nick. By converting old fields into native meadows, farmlands like this contribute to biodiversity conservation by diversifying insect communities, boosting pollinator populations, and providing critical habitat for birds year-round. “It's rewarding to see birds taking advantage of habitat in the agroscape,” Nick adds, “whether a flock of migrating Bobolinks using a field of spring cover crop or a family of rodent-devouring Barn Owls nesting in our silo.”

Of Birds and Beef

Just down the road in Huntly, farmers at Bean Hollow Grassfed are collaborating with American Farmland Trust and VWL to study how regenerative grazing practices influence grassland birds. Now in its pilot year, this project is engaging producers in several Virginia counties in an effort to identify conservation metrics that could be used to create a market for bird-friendly beef.

Beatrice and Adie Von Gontard pose with their herd of Texas Longhorns at Oxbow Farm in Front Royal, VA. Photo by Amy Johnson

Regenerative grazing is a form of agriculture that seeks to achieve improved soil health, boosted vegetation productivity, and extended grazing opportunities for livestock. There are also multiple ways that this approach can benefit birds. Earlier this year, VWL's team of biologists ventured out to Bean Hollow Grassfed and several other farms in the area to monitor nests of some of the most vulnerable grassland bird species, including Eastern Meadowlarks, Bobolinks, and Grasshopper Sparrows. The team located and monitored more than 60 nests, providing promising data to be built upon over the next few years.

“The data collected by VWL scientists has given us backup for telling our story of using innovative grazing to restore the ecological health of the farm,” says Mike Sands, owner and operator of the farm, who worked with the VWL biologists to co-design the study. “This is of significant interest to our customers,” he adds.

Which Day to Hay?

In Front Royal, a gateway to Shenandoah National Park, Beatrice and Adie Von Gontard are graced with the bubbly songs of more than 100 Bobolinks that return to the farm each year. Owners of a 1,400-acre hay operation named Oxbow Farm, the couple has collaborated with VWL for ten years, dedicating time and acres to intricate ecological studies from bird-banding and bumblebee sampling to developing metrics for bird-friendly hay. While hay production is their primary business, the Von Gontards have recognized that the Oxbow fields host some of the region's most productive populations of grassland birds. Just this year, for example, VWL biologists documented the first breeding record for Savannah Sparrows in the county.

The Von Gontards have dedicated several fields to the conservation of these delicate grassland species and changed the timing of hay harvests in some of their fields to accommodate the nesting season. “It's rewarding to alter hay timing for birds because you're giving them a chance to nest and fledge their young,” says Beatrice, who is often found waist-deep in grasses, assisting VWL biologists with their research. “And you get to see the incredible beauty of these birds in their breeding plumage, singing their melodious courtship songs and bringing food to their young. It's one of the biggest thrills of a lifetime.”

It is the Von Gontards' hope that by collaborating with organizations like VWL, they can contribute to research that lays the foundation for the widespread adoption of bird-friendly hay practices. “What I've learned is, when you farm the land in a sustainable way, you increase the diversity of species, which, in turn, makes the land a healthier and more vibrant place to live,” Beatrice adds.

The Smithsonian‘s Amy Johnson and landowner Bruce Jones meander through the native grass meadows at Jones Nature Preserve in Washington, VA, where the Virginia Working Landscapes team conducts some of their grassland bird research. Photo by Olivia Cosby

Conservation is Year-Round

Adopting conservation practices that benefit breeding grassland birds is essential for their recovery and conservation, but we mustn't ignore the needs of these birds the rest of the year. Many studies hypothesize that what happens on wintering grounds likely contributes to the decline of many of these species, yet studies of grassland birds on their wintering grounds remain limited. To help fill this gap, VWL has been collaborating with landowners to explore how winter management of fields impacts birds wintering in Virginia grasslands.

Using results from this research, the region's landowners now have the means to understand how they can optimize Piedmont grasslands both for resident and migrant species. For example, Bruce and Susan Jones of Washington, Virginia, own Jones Nature Preserve, which they carefully manage to maximize biodiversity on their property. Most of the fields there are composed of native grasses that VWL research has shown to provide critical habitat to birds overwintering in grasslands.

When left unmowed through the winter, native grasses provide thick cover, protecting birds from predators and the elements. They also maintain an abundance of nutrient-packed seeds that can sustain birds through the worst winter storms. “As the taller warm-season grasses tend to topple from the wind and snow, the seed heads stay low, and that makes for a ready food supply that also provides safety, warmth, and cover,” says Bruce, who regularly hosts workshops in collaboration with VWL and PEC to help educate community members about the importance of native plants for birds and other wildlife.

Species never or rarely seen in the area during breeding season, like Savannah, Fox, and American Tree Sparrows, flock to these fields to take advantage of the winter seed bounty. In addition, VWL biologists have documented Northern Harriers and Short-eared Owls using fields like these to roost, among sturdy clumps of native grasses that form protective dome-like shelters. While we often think of winter as the silent season for birding, places like Jones Nature Preserve remind us that our lives needn't be devoid of birds through winter — if we build it, they will come.

Wintering sparrows, like this American Tree Sparrow, flock to the native grass meadows at Jones Nature Preserve in Washington, VA, to forage for seeds throughout the winter months. Photo by Amy Johnson

Sharing the Work

The new Northern Virginia Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley BirdScape shines a light on the landscape scale and focus of efforts by VWL, PEC, private landowners, and other partners promoting bird conservation in Virginia's Piedmont grasslands. That this BirdScape includes ABC's own home office puts ABC directly in the picture, but another distinction is that this is the first in the network to be proposed not by ABC but one of its partners. This added momentum underscores the goal of the network — all working together for one objective: bird conservation.

| Amy Johnson is a Conservation Ecologist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and Program Director of Virginia Working Landscapes. |

| David Wiedenfeld is ABC's Senior Conservation Scientist. |