Chasing “Paper” Kites

ABC and International Paper are working together to improve land management practices and help Swallow-tailed Kites and other wildlife rebound.

Quaint shops, historic buildings, and stately Live Oaks beckon tourists to the small coastal city of Georgetown, South Carolina. But those cruising the south edge of town get quite a different view, suddenly shrinking before a steaming colossus of cement and steel.

Since its machinery powered up in 1937, International Paper's Georgetown Mill has fueled the region's economy. During World War II, it churned out C-Ration boxes that were packed and loaded onto ships bound for troops in Europe and the Pacific. Today, the plant employs more than 650 people and makes envelope and printer paper, card stock, and fluff pulp used in diapers, toilet paper, and personal products. A nearby container plant produces the cardboard delivery boxes that appear regularly on many of our front doorsteps.

A giant paper company and its mill might seem antithetical to the cause of bird conservation. Yet today, International Paper (IP) plays a growing role in this arena. It belongs to the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), and the wood it buys from landowners and forestry companies must meet sustainable criteria that include steps to conserve birds and other wildlife. ABC works with IP on these efforts. That's how, one morning this past July, I wound up standing on private forest land a short drive from the mill. There, I met my colleague EJ Williams, ABC's Vice President for the Southeast Region, who advises IP on where the best conservation opportunities lie for the company and its SFI partners.

“Before this was a tourist town, it was a mill town,” she tells me. The acreage we visit sits center-stage in the growing partnership between IP, its SFI partners, and ABC. Managed with purpose, it supports a far wider range of wildlife than would many other land uses. One beneficiary of this partnership is the iconic creature we came to see — a species that in their field guide Hawks in Flight, bird experts Pete Dunne, David Sibley, and Clay Sutton call “the most graceful flier of any North American raptor” and, by some accounts, “the continent's most beautiful bird.”

We've parked on a muddy forest track and are scoping a recently harvested area dotted with young pines, Sweetgum saplings, and wildflowers and backed by an army-green wall of Baldcypress and Loblolly Pine. Williams says a kite pair recently finished nesting here for the year. It's 9 o'clock and sunny. That means rising, invisible air columns, or thermals, likely beckon raptors to soar.

“There you are,” says Williams, nodding up at three sleek, white birds suddenly wheeling overhead on black-edged wings, their forked tails swiveling. “Just look at the way they use that tail as a rudder. They're right near the first nest site. That one with the short tail is this year's bird.”

Of Birds and Business

The Swallow-tailed Kite once nested in 21 U.S. states as far north as Minnesota. The species dramatically declined from the late 1800s into the 1900s — a time of widespread, uncontrolled habitat loss in the East. Other contributing factors may have been shooting and egg-collecting, since Swallow-tailed Kite eggs fetched exceptionally high prices among competitive Victorian-era hobbyists. Today, the vast majority of U.S. Swallow-tailed Kites nest in just six southeastern states, including South Carolina, where Williams and other conservationists hope to secure their future.

“The flagship bird for the Georgetown mill and 50 miles around it is the Swallow-tailed Kite,” Williams says as we watch the circling birds. “Customers want to know their products come from well-managed forests,” she says, “and birds like the kite can tell you a lot about whether those forests are being managed sustainably.”

Although many people think IP owns expansive forests, it doesn't. Instead, to get the fiber needed for numerous household staples, the company relies upon large forestry companies that partner with SFI and, especially in the South, thousands of private landowners. “The majority of the South's forest land is privately owned by individuals and families — millions of acres,” points out Williams.

As a large, well-respected business, IP can influence how its private partners think about and manage their acreage. “IP's goal is to buy 100 percent of their wood from forests that are verified as sustainably managed,” Williams says. “This raises the bar for private individuals who want to sell to IP, including those who see forest management on strictly economic terms.”

When their land is managed sustainably, private landowners not only harvest trees, which go into valuable products, but also manage and re-plant their forests for long-term benefits to local economies, water quality, carbon sequestration, and wildlife.

“Most of the landowners we work with are great stewards of the land,” Williams says, “and the kites give us a chance to enhance habitat conditions for this species and a bunch of other wildlife.” She keeps an eye out for a key element to kite nesting success: tall, open-crowned Baldcypress and pine, and sometimes oak or Sweetgum, that rise above surrounding vegetation, especially those growing along water courses. Managing wide, wooded streamside buffers as part of the working landscape benefits not only nesting kites, but also water quality, aquatic life, and habitat for declining bird species including the Kentucky Warbler.

Recent happenings have further convinced Williams of the growing synergy between forest management and conservation. Last spring, she found perfect kite habitat in the nearby Carver's Bay area. She discussed the importance of the area to the Georgetown kites with Jeremy Poirier, IP's Global Fiber Projects Sustainability Manager. Then, she worked with IP to incorporate kite habitat conservation measures directly into a planned harvest in the area.

Soon after, IP contacted the landowner, who was willing to retain an important area with towering trees that make ideal nest sites, and to delay harvest of the surrounding pine stand until after the nesting season. “Conservation can sometimes be a slow process,” Williams reflects, “but in this case, the area went from routine management to providing a place for kites to nest, now and in the future, in less than four hours!”

Raptors by Day, Hunted by Night

Masterful aerialists, Swallow-tailed Kites snatch dragonflies, cicadas, June beetles, and other large insects from the air. They also set their sights on trees and shrubs, plucking from the foliage and branches treefrogs, lizards, snakes, and some nestling songbirds — including, on occasion, gnatcatcher chicks in their nests. This larger prey is most often brought back to the nest for the young, as are entire paper wasp nests full of protein-rich larvae.

After the circling kites drift out of sight, we get into Williams' cardinal-red SUV. She wants to show me a few more nest sites. “Swallow-tailed Kites are not really birds of dense forests. They take advantage of a mosaic of conditions,” she tells me while navigating ruts in the pale-yellow mud. We swish out of the sunlight of a recently cleared forest, into a shady forest patch, then into sun again, stopping by a group of tall Loblolly Pines. A stick nest sits in the crown of one tree, a tuft of Spanish Moss dangling off one side.

Williams explains that the kites often nest in trees 60 to 70 years old that reach 80 to 90 feet tall. Many of the pine stands in the area, however, are harvested every 20 to 25 years, underscoring the importance of conserving older kite-nest trees, especially since pairs often return to the same place year after year.

From their nests, the kites get a masterful view of their surroundings … during the day. At night, though, Great Horned Owls will target the treetop kites as they sleep, dragging off adults and nestlings. Sometimes they return to a nest night after night until no birds are left. In the end, there are risks to top-end living.

Tracking Kites

Williams works with two scientists who also know a thing or two about kites. In fact, Ken Meyer and Gina Kent of the Gainesville, Florida-based Avian Research and Conservation Institute (ARCI) have handled, tagged, and tracked more than 480 Swallow-tailed Kites — far more than anyone else on the planet. Their decades of painstaking research revealed many of the life-history details now guiding conservation of the species, including a clear picture of the kite's U.S. nesting requirements and status, and the pathways and perils faced as these birds migrate.

Before tracking technology, most ornithologists believed that U.S.-nesting Swallow-tailed Kites only migrated over land, tracing the Gulf Coast shore, and that they wintered in northern South America. “In 1996, Microwave Telemetry, a company in Maryland, produced a remotely tracked satellite transmitter light enough to fit the Swallow-tailed Kite,” says Meyer. “We tagged six kites that year in Big Cypress Swamp [in Florida]. That was the beginning of the golden era of bird tracking. That's how I discovered where Swallow-tailed Kites go for the winter and how they get there. It's far away.”

Tracking records reveal that each fall, an estimated 70 percent of the species' U.S. population crosses the Gulf of Mexico from Florida, passing over 450 to 600 miles of open water to the Yucatán Peninsula. There, as revealed from tracking studies by ARCI's collaborator Jennifer Coulson at the Orleans Audubon Society, the birds join coast-hugging kites from Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, plus the few that nest in East Texas, wending their way over land through Central America to wintering grounds in southern Brazil and Bolivia — 5,000 or more miles away.

Last spring, Williams and the ARCI scientists set out to find, tag, and start tracking the movements of kites nesting in these Georgetown forests. Once they located nests during roadside surveys, the next step was to determine who owned the land so they could get permission to enter and trap the birds. That assistance and information came from local foresters at White Oak Forest Management. It turned out the kites were nesting on land owned by two long-term ABC partners, Resource Management Service and Forestry Investment Associates.

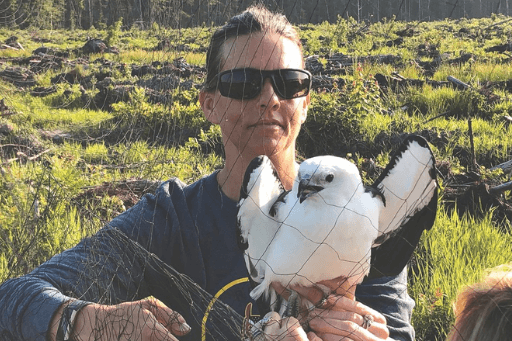

Using a large mist net backed by a perched, trained Great Horned Owl “irresistible” to nest-defending kites, the team quickly and safely trapped and attached GPS-tracking devices to three kites this past June on the forest lands we now visit. After carefully removing the birds from the net, they then fit a harness on each one that holds a GPS-equipped, solar-powered transmitter that connects with cellphone networks. Three inches long and one inch wide, each device weighs just a few grams, or less than 3 percent of an adult's weight.

As the kites traveled this past fall, the transmitters collected location data that was downloaded once a day to cellphone towers within reach of their signals. But what happens when these migrants pass through remote areas? “When they are out of range,” says Meyer, “we don't get data. But when they get back within range, the transmitter dumps all that GPS data. We just have to be patient as we wait.”

The team looks forward to the kites' spring return and to analyzing their northbound routes. They plan to expand this work over the next three years to include more nesting kites, particularly in Georgia, Florida, Alabama, and Louisiana.

Bustling Roosts, Rising Numbers

Despite spiking human population growth and development in the Southeast in recent decades, the Swallow-tailed Kite population seems to be on the rise. Since 2006, Meyer and Kent have annually surveyed, by plane, the largest-known post-breeding roosts of these birds in Florida, which number from 100 or fewer to several thousand birds each. “These large roosts provide a great opportunity for population monitoring, a gift we don't have for most species,” says Meyer.

“What we're seeing in the last six or seven years, since about 2015,” he continues, “is a very slow but steady increase in our trend index for the U.S. breeding population, which now stands at just over 11,000 at the peak of the largest roosts. This translates into an estimate of at least 15,000 to 25,000 Swallow-tailed Kites in the U.S. breeding population.”

READ MORE: Hazardous Hygiene

Every nesting season, Swallow-tailed Kites straddle a fine line between cleanliness and calamity. Unlike most raptors, young Swallowtails drop waste in the nest, not over the edge. “It gets pretty messy up there,” says Ken Meyer, Executive Director at Avian Research and Conservation Institute. “Parents bring soft nest materials, and they are continually putting new layers down, covering waste in the nest.”

They continue this throughout the nesting cycle, frequently returning with Spanish Moss, an epiphyte that acts as a cushion between the young, the nest's stick structure, and the waste. Paper wasp nests also prove handy for this purpose, after the adult kites pull off the chambers' caps, pluck out the larvae, and feed them to their nestlings.

Meyer and his colleagues have found that these “cover-up” materials really stack up. In fact, after weighing nest contents, they found that sticks make up only about half the weight of a Swallow-tailed Kite nest; epiphytes constitute the rest.

“This makes it cleaner,” says Meyer, “but all that material fills up the concave cup of the nest and makes it flat or convex.” That can be a problem, since one of the leading causes of nest failure in this species is young toppling from nests. “They're getting bigger as their nest is getting smaller, more fragile, and filled — all probably lending to getting them blown out of the nest,” Meyer says. So, at least in this one natural example, sometimes there could be a danger in too much house-keeping.

Part of this increase, Meyer hypothesizes, may be due to the birds' ability to nest in human-inhabited areas that maintain enough tree cover and provide a banquet of treefrogs, lizards, dragonflies, and other food — yet lack habitat components attractive to the birds' owl nemesis. However, working forests provide the most expansive patchworks of open areas and forest blocks and are likely key to the birds' present and future.

“All in all, this managed forest landscape works for birds far better than intensive agriculture or housing,” says Williams, as we bump our way back to the first nest site, where I'd left my car. Our short drive demonstrates her point perfectly: We rumble past flashy Red-headed Woodpeckers, drab immature Orchard Orioles, a Wild Turkey hen with six gangly poults in tow, and bluebirds. It's late in the nesting season, so we don't hear the Painted and Indigo Buntings, Blue Grosbeaks, and Yellow-breasted Chats, but Williams assures me she heard them singing in the brush all spring long. “The clearings here are packed with birds,” she adds, skirting a pothole, “and, of course, they can become kite food, too.”

| Howard Youth is ABC's Senior Writer/Editor, and is the author of Field Guide to the Natural World of Washington, D.C. |