Hazardous Protections: The Challenge of Shielding Birds and Farmworkers from Pesticides While Temperatures Rise

In June in Central Valley, California, migrant farmworkers rise before the sun. They wrap themselves tight in personal protective equipment — socks, boots, a bandana, gloves, goggles, and, finally, coveralls. They're in the field by 4 a.m. The field is dark, save for distant wildfire's flickering flame. As the sun rises and the hours go by, the thermometer ticks above 80 degrees Fahrenheit.

From dark to dawn and dawn to dusk, the worker is helping haul more than two tons of the day's tomatoes to trucks.

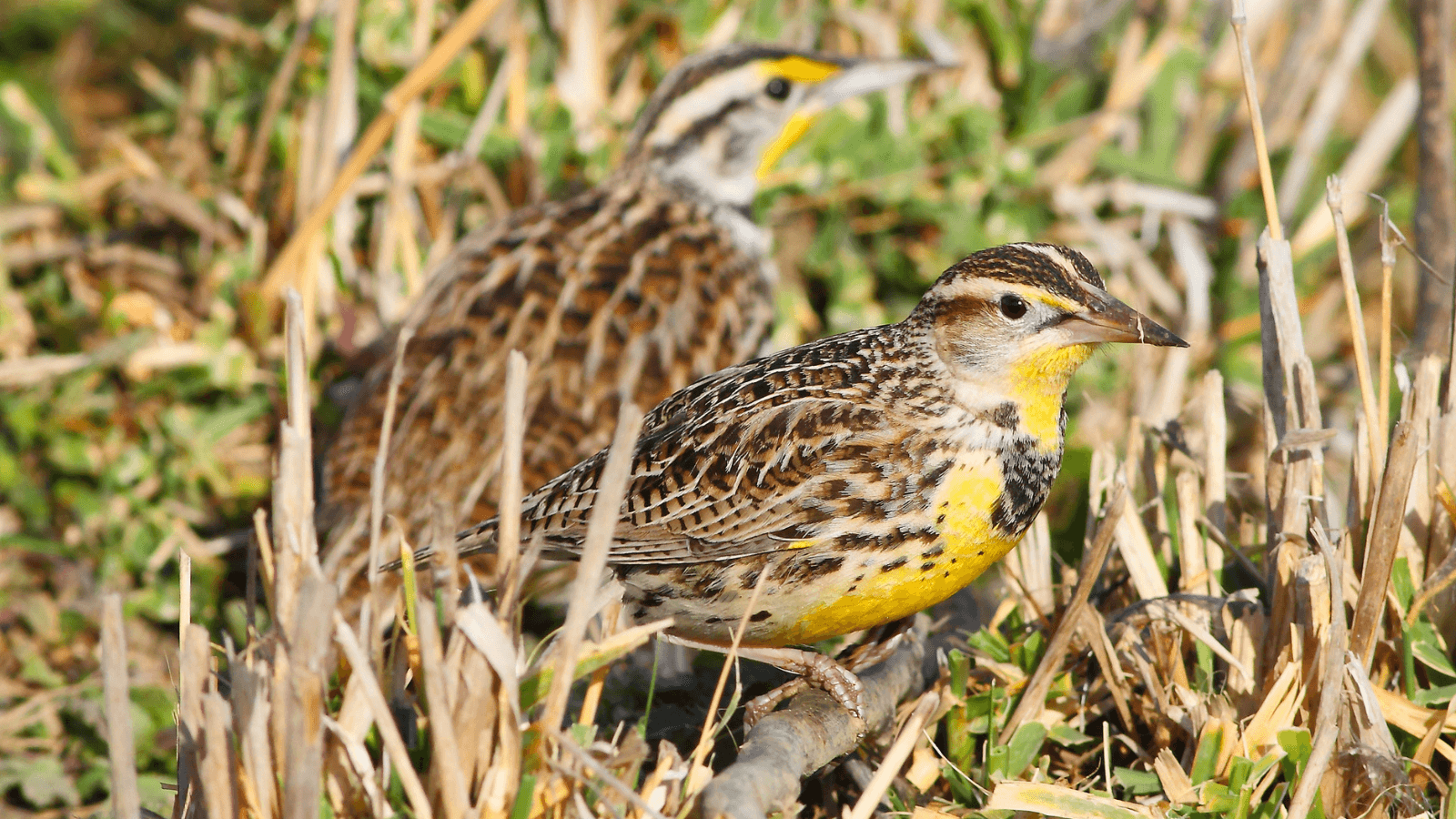

Idling truck engines drown out Western Meadowlark calls. Out this way, there are few insects left for them. The morning crickets haven't buzzed for weeks. Pluck, pluck, pluck — among the morning rush of farmworkers a few meadowlarks peck pensively at the ground looking for seeds.

Each second is precious to a migrant farmworker — no water, no bathroom breaks, no standing in the sparse shade — all to make minimum wage. Marching up and down rows of produce, the farmworker bakes because the heat they generate in their personal protective equipment (PPE) has nowhere to dissipate. By daybreak, they consider shedding the coveralls that are supposed to keep them safe. At mid-morning, the field shimmers: the crops are coated with ash and sweat and recently applied organophosphate insecticides.

Come noon, with their cumbersome coveralls on, the workers move like their boots are cinder blocks. Ring, ring, ring — they're saved by a call for the weekly training. Men and women, well-meaning, talk at the workers for a while on the dangers of the treated field, PPE, heat, and pesticide labeling. At the end of the day, the workers trudge back to crowded labor camps with pesticide residue that lingers on their fingers.

This is “danger season,” as the Union of Concerned Scientists called it. From May to October, outdoor temperatures are rising above 100 degrees Fahrenheit across much of the continental U.S. Precipitation in some places is declining precipitously and sources of water vanish; in other places, flooding occurs. Raging heat waves cause debilitating illness and death and ignite wildfires that threaten to consume what's left of North America's forests from east to west.

Humans have not evolved to tolerate these levels of heat stress, but farmworkers find themselves suited up in PPE to shield themselves from chemical threats. Nothing gets in, nothing gets out. But the problem is therein sealed: It's too hot outside to keep using pesticides.

Over 250 million acres, or 10 percent, of U.S. land area is crop fields. Each year, one billion pounds of seeds, sprays, and pellets are used to suppress pests. More will be needed to protect the agriculture sector's leading commodities: as temperatures rise, crops will become more vulnerable to disease, pests, and heat stress. Without a change, greater volumes of liquid-based pesticides would need to be sprayed to replace what has evaporated away. Pesticide-treated seeds were introduced as an alternative to spraying in the 1990s. Today, neurotoxic neonicotinoid (often shortened to “neonic”) insecticides are the standard.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has worked to educate farmworkers and help them navigate the treated field safely. With public partners they developed trainings on the hazards of planting, picking, spraying, and clipping pesticide-treated crops; putting on, taking off, and cleaning PPE; the symptoms of pesticide-related disease; and how to read pesticide labeling. Most trainings are only in English. Those labels are mostly in English. This is inadequate for the two-thirds of farm workers who speak primarily Spanish. So, the EPA produced a Spanish-English bilingual training video on the dangers of pesticides.

Since migrant farmworkers in 45 percent of states have a “piece-rate” wage — for each bucket or bag or pound or piece of crop they pick they receive pay — many ignore workplace hazards in an effort to make minimum wage. Workplace dangers are, at best, a secondary concern. Pesticides remain a major hazard to farmworker health, but there is an opportunity to address this threat and improve working conditions in an upcoming piece of legislation called the Farm Bill.

Right now, in July 2023, legislators are negotiating the Farm Bill, a sweeping piece of agricultural legislation with the power to influence the way that pesticides are labeled and regulated. Possible pesticide-related improvements that could be included in this year's Farm Bill include better multilingual labeling requirements; stricter requirements to report damage to human and wildlife health from pesticides use or misuse; and measures that make it easier for localities to pass their own pesticide regulations so that they don't have to wait on the state and federal government. These changes, and more, would make a big difference for birds as well as people.

Insect populations are declining across farmlands due to overuse of pesticides, and birds are starving without these species. Birds also look to the field floors for feed, but a single seed treated with neonics carries enough poison to kill a songbird or 80,000 bees. Populations of larger bird species that thrive in a warming climate will need even more food to eat in this landscape of scarcity. Unfortunately, birds are likely to feel the effects of acute neurotoxic poisoning long before they learn to avoid coated seeds.

It's time to push for greater funding for Education, Insurance, and Research programs, notably through the United States Department of Agriculture, that support alternatives to conventional farming practices, such as agriculture without pesticide-coated seeds. The Farm Bill contains nearly $500 billion dedicated to influencing the landscape of U.S. agriculture and is the largest singular funding source for conservation.

With the American Bird Conservancy you can sign our action alert to speak up for a stronger Farm Bill for birds and farm workers. And in states like California, Minnesota, and New York, legislative efforts to improve regulations around pesticides are underway, so residents of these states can maintain momentum around these efforts by contacting your state's congressmen and women. But, of course, some of the most profound actions you can take are right in your backyard and at your local farmer's market: growing your own pesticide-free produce and supporting local farmers who do the same. All actions to protect people and wildlife from pesticides are necessary if we are to safely beat the heat.