How Green is the Wind Industry?

One could believe that the wind industry, with its focus on renewable energy, would also be a consistent champion of wildlife conservation, but it doesn't always behave that way.

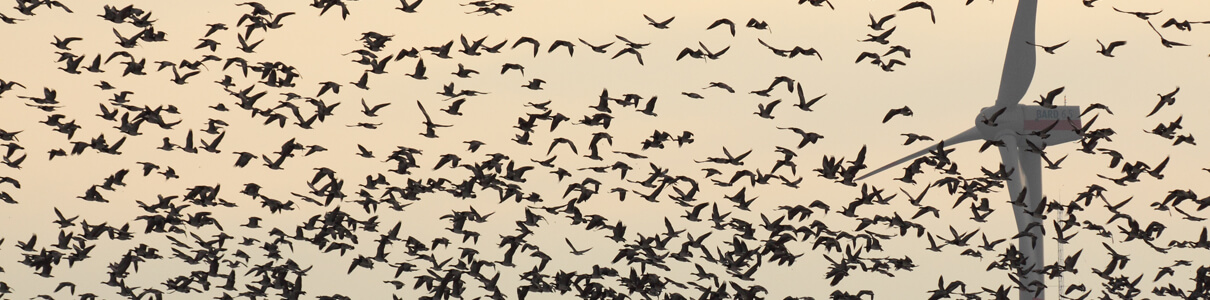

Scientists estimate that hundreds of thousands of migratory birds die each year from collisions with the fast-spinning blades of wind turbines. This number is increasing as wind developments spread further across the landscape: Tens of thousands of turbines are already located within sensitive bird habitats, with thousands more planned.

Birds and wind turbine, Bildagentur Zoonar GmbH/Shutterstock

A major problem with "green" wind power is the flawed voluntary system by which wind companies are permitted to assess bird impacts and develop bird protection plans. Under regulations promulgated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, compliance with siting and operational considerations that take bird mortality into account are wholly voluntary. You wouldn't try to protect pedestrians and drivers from collisions by making speed limits or stop signs voluntary, so why try to protect birds that way?

Environmental assessments, along with more stringent environmental impact statements, are designed to predict the environmental impact of development projects and—if needed—adjust their construction and operation to minimize harm. However, federal law only requires these site-specific assessments for the relatively few wind projects to which the government is connected in some way, such as those built on public land.

Moreover, those assessments that are federally required are frequently conducted by consultants whose paychecks come from the very wind companies whose projects they are charged with assessing—a clear conflict of interest. Other projects are left completely to the discretion of wind developers, and are potentially susceptible to manipulation.

Consider, for example, the 48-turbine New Era Wind Energy Project proposed for Goodhue County, Minn., where a consultant-generated eagle assessment appeared to significantly underestimate the project's risk to Bald Eagles. Independent mortality estimates generated by the Fish and Wildlife Service for the same project were at least 18 times higher than those developed by the company's consultants. The company's belief that the now-canceled project would have killed fewer than one Bald Eagle per decade seemed overly optimistic for an area with a population of more than 400 Bald Eagles.

Another example of a site-specific study gone wrong was a consultant-generated assessment for a wind turbine planned at the Camp Perry Air National Guard facility in Ohio, which declared that the project would have no significant environmental impact.

Not so fast: Fish and Wildlife found the assessment to be "entirely lacking" in its consideration of effects to endangered species such as the Kirtland's Warbler—among other shortcomings. In fact, even after the assessment was amended based on federal biologists' input, Fish and Wildlife still found 32 separate deficiencies in the version that the Camp Perry facility considered final.

Kirtland's Warbler by Joel Trick, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The problem with such assessments is not limited to the United States: A similar situation occurred when SouthPoint Wind proposed an offshore turbine project in Lake Erie, close to Point Pelee National Park, Canada—one of the world's best-known bird migration hotspots. During the project's evaluation process, the Essex Region Conservation Authority, which represents local municipalities, commissioned an independent study of the company's environmental screening report. The study concluded that the data collection SouthPoint had used to determine the area's significance for birds had been "grossly inadequate."

How could expert consultants have generated these studies—and the developers been willing to advance these projects—when so much of the relevant information about their potential impact was widely known even by amateur ornithologists familiar with these areas?

The answer could be that more rigorous assessments, especially when endangered species are involved, can trigger additional levels of federal scrutiny that can delay or even halt the projects.

Fortunately, in the case of Camp Perry, the Department of Defense did the right thing and withdrew the turbine proposal following citizen complaints over bird impacts. New Era in Minnesota, too, was abandoned, partly due to concerns about the excessive number of eagle deaths it could have caused. SouthPoint foundered following citizen complaints, as well.

Bald Eagle by Sergey Uryadnikov, Shutterstock

Access to assessment data on such projects is not always so readily available to the public, though. Only the wind companies and their consultants really know how many wind-turbine projects that are proceeding are also downplaying bird concerns in their assessments and plans.

American Bird Conservancy and our Bird-Smart Wind Program supports wind development and the companies and consultants that are doing their best to protect birds and other wildlife. However, the current voluntary system enables those who fail to properly consider bird impacts to tarnish an industry that as a whole presumably aims to do the right thing when developing renewable power.

There is a way to fix this problem: Establish and fund a federal permitting system for wind projects that requires siting and operational input from federal wildlife biologists, both during the assessment process, and in response to any recorded bird mortality. Doing so would level the playing field for operators who intend to play fair—and protect our birds, too.

A version of this article first appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on October 26, 2015.

Mike Parr is ABC's Chief Conservation Officer. He joined ABC in 1996 after graduating from University of East Anglia, UK, and working for BirdLife International. He has authored three books: Parrots – A Guide to the Parrots of the World, Important Bird Areas in the United States, and The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation, along with numerous articles and papers. He is on the committees of ProAves Colombia and is Chair of the Alliance for Zero Extinction. Follow him on Twitter: @michaeljparr

Mike Parr is ABC's Chief Conservation Officer. He joined ABC in 1996 after graduating from University of East Anglia, UK, and working for BirdLife International. He has authored three books: Parrots – A Guide to the Parrots of the World, Important Bird Areas in the United States, and The American Bird Conservancy Guide to Bird Conservation, along with numerous articles and papers. He is on the committees of ProAves Colombia and is Chair of the Alliance for Zero Extinction. Follow him on Twitter: @michaeljparr