Passing Through: Migratory Connectivity and the Gulf of Mexico

An Interview with Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center's Emily Cohen

Bird migration in the Western Hemisphere is in full swing! We caught up with Emily Cohen, a Research Associate with the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center who is working on migration biology and especially with birds migrating across or around the Gulf of Mexico, to find out what's new in the science of bird migration. ABC uses data from SMBC and many other organizations to guide the work of our Migratory Bird Program.

New technology and boots-on-the-ground research help biologists better understand when and where migratory birds, such as this Ovenbird, travel around the Gulf of Mexico and between their breeding grounds and wintering habitats—an area of research known as "migratory connectivity." Photo by Gerald A. DeBoer / Shutterstock

Jennifer Howard, American Bird Conservancy (JH): What is migratory connectivity, and what questions are you trying to answer through your research?

Emily Cohen, Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (EC): Migratory connectivity is the study of how populations are linked between seasons. Take Ovenbirds that breed in Maryland, for example. Where do they spend the winter and what routes do they take for spring and fall migration? You really need to have that information to understand how specific populations are doing.

We're focused on the Gulf of Mexico as a bottleneck for migratory landbirds — one they have to move through every spring and fall. We're trying to understand the extent to which events that occur during migration might influence breeding populations of these species. We compare data from multiple sites, so we can look at the distributions of bird populations not just at a single site but around the Gulf.

Our work started with Mad Island, but we've expanded from that banding site to also using tracking, Cornell Lab of Ornithology's eBird data, stable isotopes, and weather radar to detect migrants. This is just a super-exciting time to be studying migration biology, because we have all of these new technologies as well as better and better analyses.

JH: How does weather radar help you understand bird migration?

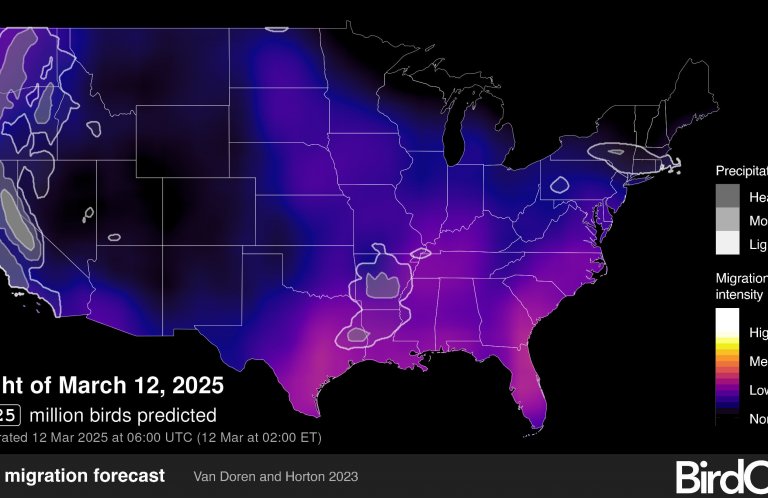

EC: Weather predictions are based on information from stationary radar stations that collect data 24 hours a day. What's cool is that weather radar also picks up biological elements. When radar stations shoot out those radar beams, they also hit insects and birds moving through the airspace. So we do the opposite of what meteorologists do — we filter out the weather and look at the birds.

We're using data from 12 radar stations from the Florida Keys to Texas. The data go back 20 years. It's probably the largest dataset of animal migration in the Western Hemisphere, and it's freely available.

Emily Cohen and her team use mist nets to safely capture migratory birds, such as this Prothonotary Warbler. They attach an identifying band to each bird's leg and also collect biological samples and health data to better understand how the birds are affected by their journeys. Weather radar provides additional information about migratory connectivity, such as where and when the birds are traveling through the region and visiting different habitats. Photo by Danielle Aube

JH: What do you do with that data?

EC: If you get the correct time, right after sunset in the evening, that's when birds are lifting up out of the habitat and flying into these radar beams. From that, you can find the stopover habitat they're coming out of. So we can build maps of where migrants are using habitat around the whole U.S. Gulf Coast during spring and fall.

We're also looking at airspace as habitat. We can use the radar beam that's pointed upward to look at where birds are moving through the air, where the flight corridors are, and what characteristics of the air make it good habitat.

JH: What do you mean by “airspace habitat?”

EC: It's easier for us to think about how the landscapes are changing — from climate change, pollution, and habitat destruction or degradation from human activity — but the airspace is also changing. We're building and adding artificial light and radio and cellphone towers. It's really exciting to think about putting those pieces of the puzzle together.

JH: Are there limitations to the radar data? And how does it fit in with the other techniques and kinds of data you use?

EC: You can't identify individual species with weather radar data, but we can get that information in other ways. One way is by working with eBird data to model species-specific data around the Gulf. Collected by citizen scientists, this data tells us about species distributions, when those species are moving, and which habitats they prefer.

We collect data from three different banding stations — in Texas, Florida, and Louisiana — during spring migration. The objective is to find out more about these birds that passed through these three areas.

Tim Guida collects data and assesses the health of a migratory bird at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center's bird banding station at The Nature Conservancy's Clive Runnells Family Mad Island Marsh Preserve on the Texas coast. The data provides important clues about migratory connectivity — for example: Are the birds finding enough food to maintain a healthy body weight? Photo by Autumn Lynn Harrison

And we use stable isotopes that we get from the feathers and toenails of the birds we catch. We pull one feather and analyze the values of deuterium — a hydrogen isotope — which varies according to the birds' breeding latitudes. The hydrogen value in that feather is a signature of where the birds are going. It's not perfect. It's not going to tell you Bethesda versus Baltimore. But it tells you the latitudes they are headed to — Maryland or the boreal forest.

So the radar data gives us distribution — where the migrating birds congregate in stopover and airspace habitat around the Gulf Coast. The eBird data looks at species distribution as a companion to the weather radar. Isotope data tells you which populations within that species occur in certain areas. And the banding data that we collect at Mad Island and elsewhere gives us information about passage timing and the condition of individual birds.

JH: Tell us more about Mad Island—why is that stopover habitat so important?

EC: The flight across the Gulf of Mexico is a 15-to-20-hour flight, so many birds arrive very skinny. They land for a day or two to refuel. It's critical for them to be able to refuel quickly and safely so that they can continue their journey to arrive at their breeding sites in good shape. Those birds do better.

We get some birds that are like little butterballs, because they have fat stored all around their body for long flights. And we also catch birds that are super-skinny. Once they burn all the fat when they're on a sustained flight, they start burning muscle. When we catch those super-skinny birds, we don't hold onto them long, because they really need to get back in that habitat and refuel. That's why high-quality habitat like Mad Island is so critical.

JH: Can you give an example of other stopover habitats?

EC: In Louisiana, there are patches of coastal chenier forest of live oak and hackberry that are like islands for migrants. On one side of these forest patches is the Gulf of Mexico and on the other side is miles and miles of open marsh. These oak and hackberry forests are really important habitat for birds recovering from and preparing for the long flight across the Gulf of Mexico.

Louisiana's coastal live oak and hackberry forests—known as chenier forests—provide much needed forage and shelter for migratory birds that have just completed their flight north across the Gulf of Mexico, or are just about to embark on their journey south. Shown here is the Chenier au Tigre in Louisiana's Vermilion Parish. Such stopover habitats are essential for maintaining migratory connectivity between birds' winter and summer habitats. Photo by Erik Johnson / Audubon Louisiana

JH: Is migration biology a relatively unusual or new thing to study?

EC: According to our recent review of the animal ecology literature, the majority of bird studies still occur during just one part of the life-cycle: the breeding season. That bias is limiting our ability to understand why so many of our migratory populations are declining. We need to understand how populations are affected by events that occur throughout their full annual lifecycle — during migration and in the winter, as well as during the breeding season.

Take a migratory species that flies from Michigan down to Texas and then over the Gulf of Mexico to spend the winter in Belize, and then back in the spring. What happens over the winter and during those migratory journeys can limit populations through mortality, or influence the survival or condition of birds during later phases of their annual cycle.

We need to understand not just where a population is moving during migration but also when — early or late in the season. We have hurricanes and floods, for example, that come through the Gulf Coast at different times. And even regular habitat characteristics change depending on the time of the season. In the early fall, you might have abundant food when some plants are fruiting, and then later in the season not so much. To understand if or how these events contribute to population declines, we need information about the spatial and temporal distributions of species and populations throughout the annual cycle.

What's going on during these journeys is the final frontier for migratory bird biology. We're using all these established and emerging tools, and figuring out so much exciting information right now!

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the spring 2017 edition of Bird Conservation magazine.

| Jennifer Howard is Director of Public Relations at ABC. She was a writer and reporter with The Chronicle of Higher Education for 10 years and before that was a contributing editor and columnist with The Washington Post. Follow Jen on Twitter at @JenHoward. |