Should We Stay or Should We Go Now: Evacuation from Laysan

August 5-18, 2014 | By Barbara Heindl

This past week we hit the halfway point of our 90-day tour on Laysan to monitor Millerbirds, and it showed. All of the Laysan castaways were in the groove.

We were monitoring over 10 active nests and had seen a remarkable 90 birds out of the 103 that were banded as of the end of the 2013 monitoring season. Despite all the time we had already spent in 'NIMI Land'–our affectionate name for the Millerbird breeding grounds–we were still seeing new birds, including two translocated females who had been eluding us. It is an amazing feeling, to still be solving mysteries and chipping away at remaining questions despite being on the island for over a month already.

After a full month on Laysan biologists are still finding banded birds who have eluded them until this point. Photo by Megan Dalton.

Lifestyle-wise we were also in the groove. I stopped thinking about all the fresh foods I was missing during mealtime and was delighted by new creations that seemed to come out of the woodwork. Where did this pumpkin custard come from? Beet salad? Delightful! Mango lassies? How refreshing! Living was good on Laysan.

It was in the midst of this swing that we got the news: the two tropical storms the rest of the team in the main Hawaiian Islands had been keeping an eye on had turned into three: Iselle, Julio, and Geneviève. The three of them were tracking to our southwest, south, and southeast respectively, with Julio projected to travel between Laysan and Lisianski. We were being evacuated within 24 hours by naval vessels in the area.

Last-minute Packing: 24 hours til Evacuation

The next 24 hours went by quickly. We immediately started backing up all our data and preparing camp not only for our imminent departure, but for the potential beat down from the forecasted storms. We filled buckets with sand to weigh down loose debris that birds had burrowed under, screwed all doors on our tents and structures shut, and tried to eat all the ‘good' perishable food we had been saving at the bottom of our solar freezer for later in season. Not knowing if or when we would be able to return to Laysan meant there was no way to make it last. Needless to say we all ate a lot of bacon, sausage, and cheese in those last 24 hours – even the vegetarian – but in our minds it was better than seeing all that food go to waste.

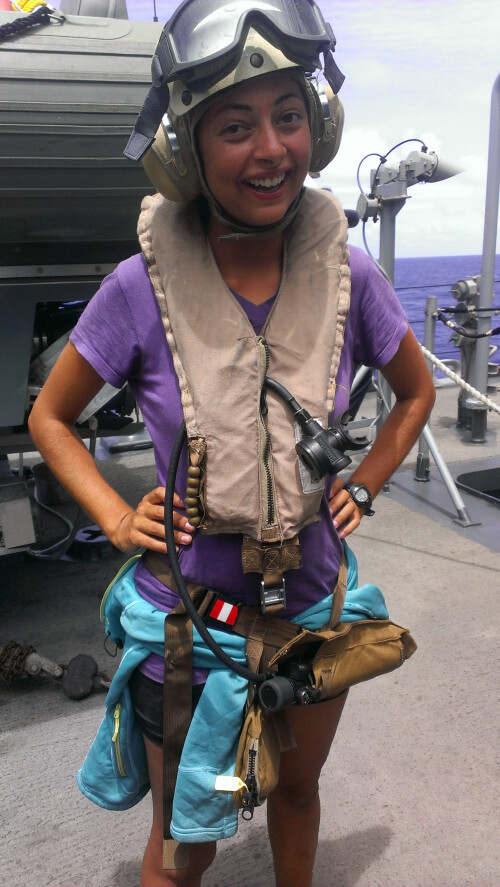

During this time we were in consistent contact with the vessel that was hopefully coming to pick us up, but it was unclear how the pickup would go. We knew the ship in the area was a well-equipped Navy vessel, but would they pick us up by helicopter or boat? Did they have boats small enough to get past the barrier reef, or would we have to swim out to meet them? Would we be able to take any personal items or were there restrictions? Once they picked us up, then what? Would we wait out the storms and go back to Laysan? Would they take us to another island in the area or were we along for the ride joining them for wherever they were heading to?

We tried our best to mentally and physically prepare for all the options, having our gear numbered and prioritized in case we could take only one bucket. Passports, wallets, and data made the first cut, cameras and laptops in the next, and everything else followed.

Operation Jackpot

Late in the evening on 7 August, we got the updated plan. The USS Comstock would be in the area at 3 am, we were to meet two metal hulled inflatable boats on our beach with all our gear at 07:30, and they would take us to the USS Comstock from there. They had ruled against a helicopter pickup to avoid the chance of hitting birds in the area, a very serious threat given the hundreds of thousands of nesting birds on the island at any given time… a number that we had told them of early on and that they verified en route. From there, where they were taking us was still anyone's guess, but they said it would most likely be their current destination of Hong Kong.

Early that morning we sadly trudged our numbered buckets down to the beach and waited to hear from the ship on our radios. It took a while to spot the carrier on the horizon, and at first glance it didn't seem that big, certainly not that much bigger than the 180 ft NOAA vessel that had dropped us off. Not long after we got the last of our gear down to the beach we got word from the ship, they were 4 miles off the coast of the island and deploying the small boats to come and get us. USS Comstock operation “Jackpot” was already underway (their name for the mission, not ours).

The crew waits with all their gear on the beach at Laysan to be picked up by USS Comstock. Photo by Barbara Heindl.

After some searching we noticed two speedy vessels aimed to the north end of the island. After a little direction they reached the edge of the barrier reef and aimed south to the only decent channel through the reef and to the beach where we waited for them. The smaller of the two boats ventured inside, skillfully giving wide birth to a young monk seal swimming in the bay. Upon getting to shore we were greeted by ‘Hey! You guys want a lift? We just happen to be in the area if you do.'

We appreciated their humor, but it was a hard question for us. We were more than thankful and grateful that they had been in the area but none of the six of us (three Millerbird and three NOAA monk seal researchers) were happy to be leaving Laysan. We were happy to be safe, yes; but our work on Laysan was definitely not done and to be leaving prematurely felt a little unsettling. Regardless we met them with a smile and started passing our buckets over. They transferred our buckets to the second small boat and came back to get us.

As we sped outside of the reef and towards the ever growing USS Comstock, it was undeniably much, much larger than the NOAA vessel that had initially dropped us off on Laysan. I looked back to see our tiny island disappearing over the horizon. That view was one I hadn't remembered getting when we were dropped off, and it was a hard view to take in not knowing, whether we would be back and if we did what shape the island would be in.

As we got closer to the USS Comstock, I remember seeing an uneasy look on one of my co-workers faces, knowing that she was prone to sea sickness and the seas were not the calmest. I remember saying ‘Don't worry, we're close.' But the boat kept going, Laysan getting smaller and smaller, the Comstock getting larger and larger, until finally we were alongside a giant windowless wall of the Navy vessel with only a rope ladder hanging down from a platform somewhere about halfway up the eight-story ship.

While staring up the looming wall, someone leaned out from the middle somewhere “Who's first? You're all being timed so make it count!” I looked down the line of the Laysan evacuees, and the designated first one up was hanging halfway off the boat, emptying out her breakfast to the fishes. The second one up was Robby, who when he realized he was next in line scaled the swinging ladder with ease.

I was next, trying to think about how Robby climbed up, did he skip rungs? How did he get up so fast? What happens when you get to the top? Where was the safety briefing on this? I tried to time jumping on with the swell and clambered to the top, trying to ignore someone yelling ‘Don't look down!' from below. All 11 of us made it up on to the boat fine. We were welcomed by the Executive Officer who took us to the Officer's Galley to talk to the ship medic, fill out health forms, and get coffee. At that point our destination was still up for debate, but his best guess was that we were going to Hong Kong.

So Where Are We Going Anyways?

The next several hours went by quickly. We were treated to a hot lunch, chicken cordon bleu with fresh salad, not what I had envisioned for my first meal off of Laysan, but it was still delicious. The Captain had us up to his office for coffee and pastries and explained the whole situation. The NOAA monk seal researchers from Pearl and Hermes Atoll and Lisianski Island had been evacuated by other ships in the fleet at the same time, so there were 11 evacuees total. We were to be flown on an Osprey (a rotational winged aircraft) to the USS Makin Island to meet up with two other evacuees and then another flight to the USS San Diego to meet with the last three, and then on to our final destination – Midway Atoll.

Given the possibilities, hearing that we were headed to Midway was a relief. From there we would be able to enter and proof our Millerbird data, assist the Midway biologists surveying local Laysan Ducks, and partake in their coveted soft serve ice cream machine while we waited for the next flight to Honolulu. The next flight was scheduled for about a week and a half later.

This emergency evacuation really illustrates how remote and exposed we were while on Laysan. With a Naval fleet already in the area, it took 30 hours from when we heard the Navy was on the way till we landed foot on Midway. I can assure you no other situation would have had us off the island sooner.

An Osprey drops the crew off at Midway Island where they meet up with other Northwest Hawaiian Island evacuees. Photo by Darlene Olsen-Host.

Back to Laysan

While we hope Laysan weathered the storms in our absence, a part of me reflects on the timing of them and their threat to the Northwestern Hawaiian Island species. Unpredictable storms like this are one of the many reasons Millerbirds were translocated from Nihoa to Laysan to create a second population. Having multiple populations helps to ensure that one poorly timed and placed storm doesn't take out all the remaining Millerbirds on the planet.

Based on the actual path of the storms, it looks like Laysan lucked out this time and none of the storms went over the island. We are all optimistic that Laysan and the Millerbirds persevered with little trouble, and are looking forward to seeing them again soon.

We flew from Midway back to Honolulu on 19 August, and then ship back out to Laysan on a NOAA boat on 30 August. We will head back to Laysan to finish our season and see how the camp fared through the storms. All of us are extremely thankful to the US Navy and Marines who picked us up and were extremely impressed with their skill and compassion during operation “Jackpot.”

Throughout the entire endeavor the Navy and Marine personnel treated us with nothing short of extreme kindness and respect. Lots of thanks also goes out to all the folks on Midway who made sure we were safe and well fed during our time there, making sure that us castaways felt more than at home, and keeping us busy during our stay.

Barbara Heindl is a field biologist on Laysan Island monitoring translocated Nihoa Millerbirds. She has also done extensive work on Kaua‘i, Alaska, and across the United States' mainland. She is originally from Wisconsin and a graduate of University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Barbara Heindl is a field biologist on Laysan Island monitoring translocated Nihoa Millerbirds. She has also done extensive work on Kaua‘i, Alaska, and across the United States' mainland. She is originally from Wisconsin and a graduate of University of Wisconsin-Madison.