About the Eared Grebe

The dainty Eared Grebe is the most abundant and widespread grebe species in the world. Although officially classified as the Black-necked Grebe by the International Ornithological Committee, it's still known as the Eared Grebe in North America. Both names refer to telltale ID features of this small waterbird, which is an eye-catching sight in its breeding plumage of black and rufous, set off by a wispy fan of golden plumes behind each vivid red eye. Its plainer winter plumage is a mixture of gray, black, and white. The small head, rounded back, and thin, slightly upturned bill are good identification marks in all seasons.

Like other birds that undertake long migrations, from the tiny Blackpoll Warbler to the imposing Tundra Swan, the Eared Grebe undergoes a series of “preflight” physiological changes.

Feasting and Flying

Migratory birds must accumulate body fat — the fuel that powers their long flights — before beginning their journeys. Eared Grebes, along with other migrants ranging from the Ruby-throated Hummingbird to the Red Knot, accomplish this quick weight gain by eating constantly. Some birds literally double their body weight! Pectoral (flight) muscles also increase in size during this time, while other organ systems temporarily shrink to accommodate these changes. Once arriving at the wintering grounds, migrants' bodies “rebalance,” then undergo these changes again before the spring migration back to their breeding grounds.

The Eared Grebe takes these physiological changes to an extreme. Its migration isn't a straight-line journey; rather, it includes months-long stopovers at “staging areas,” where the grebes rest, molt, and feed voraciously to regain fat stores lost during the first stage of their migration. During this time the grebes' flight muscles atrophy, leaving them unable to fly. Before its migration can continue, the Eared Grebe must reorganize its body composition once again, this time to prepare for flight. The mass of its digestive organs decreases by two-thirds, and the pectoral muscles increase in size. Once the grebe can fly again, it continues on to its wintering areas.

This cycle of feast, flight, and recovery is repeated as the Eared Grebe migrates north again in the spring, as well as when it pauses along its migratory route for any extended period of time. As a result of this protracted migration, the Eared Grebe has one of the longest flightless periods of any flying bird, averaging 9-10 months of each year. At its southbound staging areas alone, an Eared Grebe may remain flightless for up to four months!

Songs and Sounds

Eared Grebes give shrill, rising, rather frog-like calls on their breeding grounds.

Listen to a breeding colony on a prairie pothole lake:

And a single adult:

Breeding and Feeding

Piggyback Parenting

During courtship, Eared Grebe couples will call, posture, and approach each other in a series of synchronized moves. A pair may "dance" together by rising up in the water and paddling rapidly across the surface with necks raised.

The Eared Grebe is a gregarious, monogamous species, forming nesting colonies during the breeding season and remaining in large flocks year round. A mated pair works together to build their nest, a floating platform of soft vegetation anchored to underwater plants in open, shallow water. Nest construction takes about a week, but the pair will continue to add material to the nest throughout the breeding cycle. Both adults defend their nest from neighboring grebes and other intruders.

The female Eared Grebe lays 3-5 eggs on this watery nest platform, which both adults incubate for about three weeks. Their down-covered chicks hatch with eyes open and leave the nest immediately. They are not waterproof, so they immediately clamber onto a parent's back, where they remain for a week or more. Parents take turns ferrying their brood, while the other supplies meals to the young. This piggyback parenting continues until the young Eared Grebes grow big and strong enough to swim and forage independently.

Feather Feeder

Like the Common Loon and Canvasback, the Eared Grebe catches its prey by diving and swimming underwater. Its lobed feet, an adaptation seen in all grebes and coots, make it especially efficient at navigating its watery hunting grounds. The Eared Grebe will also glean food from the water's surface. It feeds primarily on aquatic and terrestrial insects such as beetles, dragonfly larvae, flies, and mayflies. It will also consume small crustaceans, mollusks, tadpoles, and small fish. This grebe feeds heavily on brine shrimp at staging stops along its migratory route.

The Eared Grebe, like others in its family, has a curious habit of eating its own body feathers, as well as feeding them to their young. It's actually a practical adaptation for this small waterbird's diet: The soft feathers line the bird's stomach, possibly protecting it from sharp fish bones, hard bits of shell, and other indigestible leftovers.

Region and Range

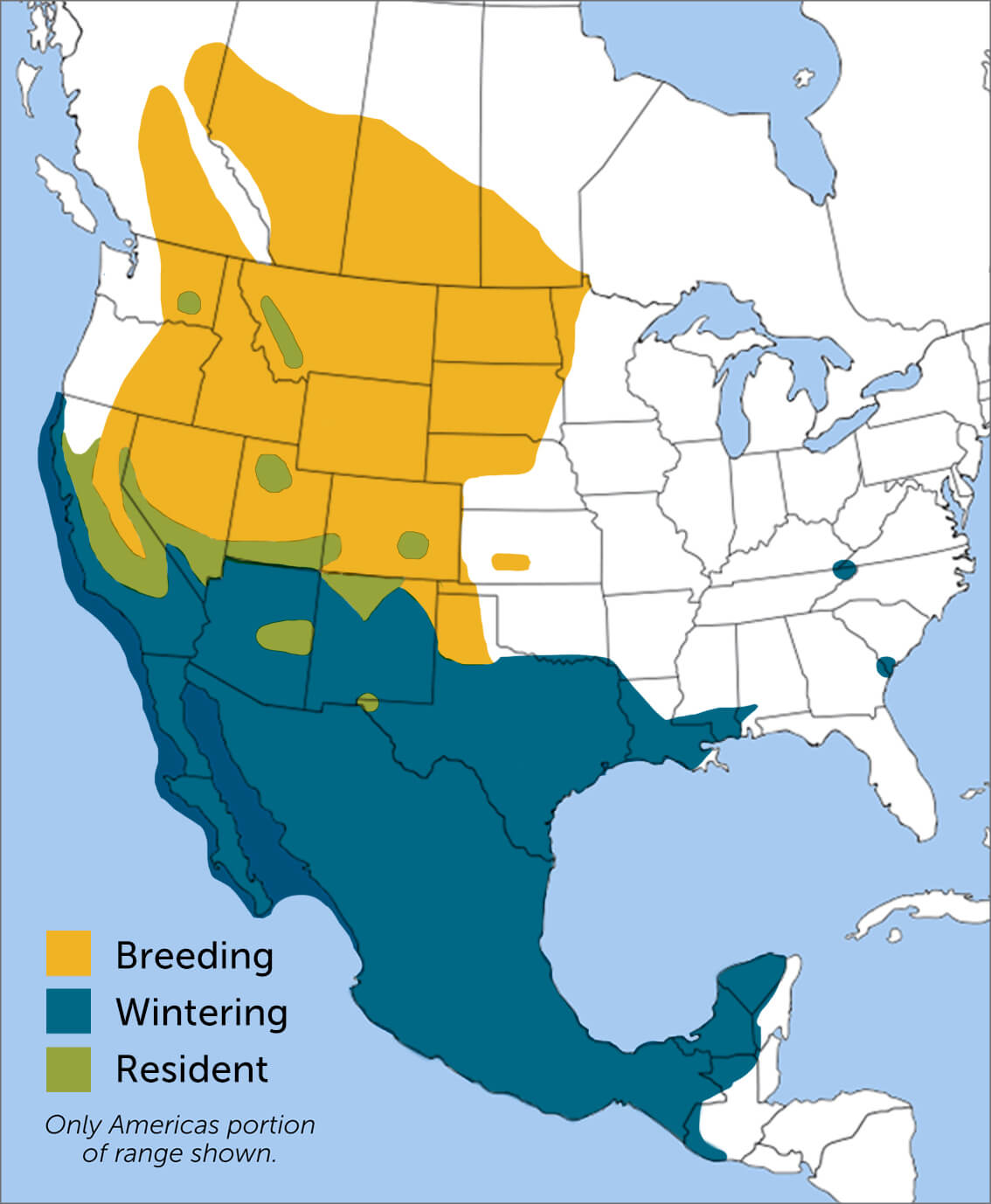

The Eared Grebe is a wide-ranging species, distributed across Europe, Asia, Africa and North America. Three subspecies are recognized. The North American subspecies, californicus, breeds from southwestern Canada through the western United States to central Mexico. North American Eared Grebes migrate as far south as Guatemala for the winter, flying at night.

There are two primary staging grounds for migrating Eared Grebes in North American: Utah's Great Salt Lake and Mono Lake, California. They gather at these staging areas in enormous flocks that can number into the millions. Almost all North American Eared Grebes molt and/or stage on these two lakes each fall!

Conservation

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

The Eared Grebe is threatened by habitat loss due to wetland drainage, drought, conversion for agriculture, and water diversion for irrigation. The North American population of Eared Grebe is highly dependent on a few staging areas during migration, so any habitat degradation in these places can have a huge impact on the species. Huge die-offs have occurred at these places, possibly due to avian flu and cholera.

In 2023, ABC joined partners in a lawsuit against Utah, charging that the state has diverted too much water from the Great Salt Lake and caused a significant drop in the lake's water levels, endangering birds such as the American White Pelican as well as the Eared Grebe. The case continues; see the latest updates here.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on migratory birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Living a bird-friendly life can have an immediate impact on migratory birds in the United States. Doing so can be as easy as adding native plants to your garden, avoiding pesticides, and keeping cats indoors. To learn more, visit our Bird-Friendly Life page.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on more than 8.5 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. That's not all: With the help of international partners, we've established a network of more than 100 areas of priority bird habitat across the Americas, helping to ensure that birds' needs are met during all stages of their lifecycles. These are monumental undertakings, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.