Birds and Other Wildlife to Benefit from Rat Eradication Effort on Remote Pacific Island

Contact: Robert Johns, 202-234-7181 ext.210,

|

White-tailed Tropicbird by Michael Walther |

(

In June, a team of about 40 staff from five organizations – Island Conservation, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS), The Nature Conservancy, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Geological Survey – launched an effort to protect and restore Palmyra by removing all black rats from the 25 islets that comprise the atoll.

Rats have severely degraded the ecosystem of this important site by preying on seabird eggs and chicks and native land crabs, and by directly competing with native species for limited food resources. Rats also limit native plant growth and disperse the seeds of introduced, invasive plants. The eradication project is expected to result in benefits for seabirds, plants, native rainforest, terrestrial invertebrates, and other components of the atoll’s terrestrial ecosystem.

This conservation action is significant because Palmyra is the only moist, tropical atoll ecosystem in the Central Pacific that is well protected. A small number of scientists and managers living on the islets prevent the exploitation of both marine and terrestrial natural resources that is prevalent elsewhere due to burgeoning human populations. Rats were likely preventing eight seabird species from successfully nesting at Palmyra and pushing some seabird colonies towards total extirpation.

The eradication effort involves the controversial aerial application of rat poison across the atoll. During an official public comment period on the proposed plan, ABC commented in favor of the eradication, but raised concerns over some of the proposed strategies, including the use of the pesticide brodifacoum and some of the application strategies.

Palmyra is inhabited by land crabs (including the world’s largest land invertebrate, the rare coconut crab), which will also consume the bait. Although crabs are immune to the effects of the chemical, any animals, such as shorebirds, that consume the crabs would be at risk.

In order to reduce non-target mortality of shorebirds, the effort incorporated several precautionary measures, including:

(1) timing the operation when the majority of birds had departed for their northern breeding grounds;

(2) placing bait stations accessible to rats but not to shorebirds at key shorebird roosting sites instead of aerially dropping bait; and

(3) capturing and holding birds until the rat removal process was finished and they could be safely released back into the wild. This last strategy was particularly significant for the Bristle-thighed Curlew, a rare WatchList species with a global population of only 2,600 pairs.

“Non-native rats wreak havoc with island ecosystems and can entirely destroy bird populations. Eradicating them is extremely difficult. We hope that the effort will succeed in Palmyra,” said George Fenwick, President of American Bird Conservancy.

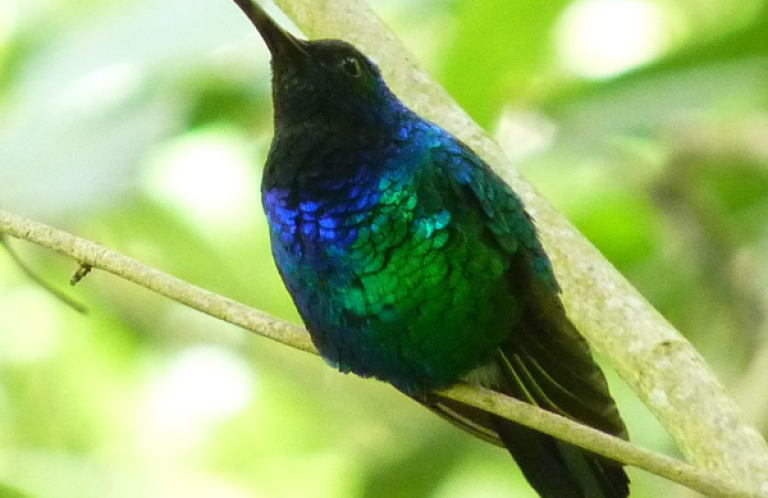

Species of breeding seabirds that will benefit from the rat removal include the Sooty Tern, Black Noddy, Brown Noddy, White Tern, and Red-tailed and White-tailed Tropicbirds. In addition, several species of seabirds were likely extirpated from Palmyra due to human disturbance during WWII and rat predation. These include the Audubon’s Shearwater, Christmas Shearwater, Wedge-tailed Shearwater, Phoenix Petrel, White-throated Storm-Petrel, Bulwer’s Petrel, Blue Noddy, and Gray-backed Tern. The rat eradication will hopefully permit recolonization by these species.

Palmyra Atoll, designated as a National Wildlife Refuge, is located approximately 1,000 miles south of Honolulu, Hawai‘i, in the central Pacific Ocean. The Refuge was established in 2001 to protect, restore, and enhance migratory birds, coral reefs, and threatened and endangered species in their natural setting.

The refuge consists of 25 islets encompassing more than 600 acres of land, including one of the largest remaining tropical coastal forests in the U.S. Pacific Islands, and 15,500 acres of lagoons and shallow reefs. The Refuge’s boundary extends seaward 13 miles, encompassing 515,000 acres of some of the world’s most diverse coral reefs.

The eradication team is expected to conduct follow-up surveys on Palmyra in August and September of 2011, and then again in 2013 to determine the effectiveness of the effort.

“What we expect to find is an island that has been ridded of a highly destructive predator—an island that has taken an important step in the right direction towards re-acquiring its natural environmental balance,” said Alex Wegmann, Island Conservation's Palmyra Project Manager.

“The native forest will start to re-establish now that seeds are free from predation by rats, land crabs will reinstate themselves as the dominant terrestrial consumers, breeding seabird populations will grow in a predator-free environment, and seabird species that are conspicuously absent from Palmyra can now find refuge on the atoll’s rat-free islands,” Wegmann added.