Conservation of Galapagos Petrels on Private Lands

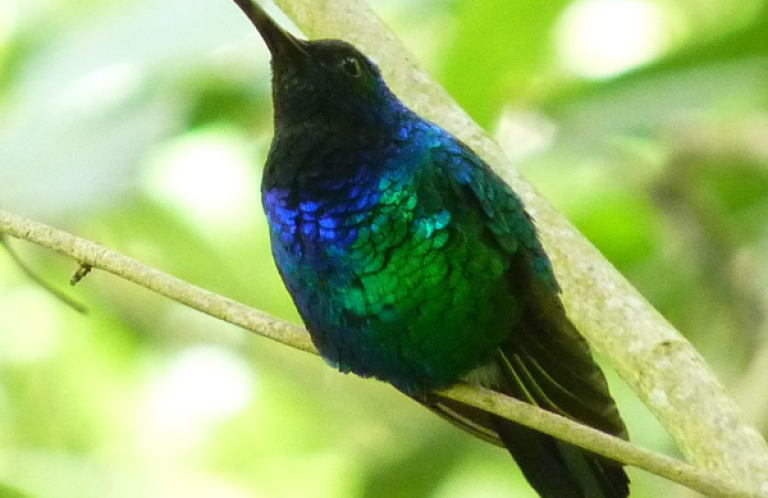

Galápagos Petrel. Photo by Dušan Brinkhuizen

(Para leer la versión en español de este mensaje, presione aquí.)

(May 4, 2022) American Bird Conservancy (ABC) is representing a collaborative project focused on the conservation of Galapagos Petrels at the 2022 World Seabird Twitter Conference. To help the Galapagos Petrel safely raise chicks and recover its numbers, ABC is working with partners to embed in-ground nest boxes at the edges of agricultural fields. The project is a collaborative effort between ABC and Conservation International, local farmers, and local consultants Carolina Proaño, Jonathan Guillén, and Leo Zurita Arthos from Universidad San Francisco de Quito.

The following is the scientific presentation:

———————

Conservation of Galapagos Petrels on Private Lands

Seabirds of the Procellariiformes order are the most threatened group of birds in the world. Their declines are related to both sea-based and land-based threats. The Galapagos Petrel (Pterodroma phaeopygia) is a seabird that breeds only in the Galapagos Archipelago. Threats to the petrel at sea include oil spills, the birds being killed as bycatch in fisheries, and loss of prey as a result of overfishing. On land, Galapagos Petrels face threats including predation on eggs, chicks, and adults, destruction of nests from livestock trampling, and habitat lost to agricultural conversion and introduced plants.

The introduced species affecting the Galapagos Petrel on land during the breeding season are dogs (Canis familiaris), cats (Felis catus), pigs (Sus scrofa), and rats (Rattus spp.). All prey on petrel eggs, chicks, and occasionally, on adult individuals. Domestic livestock such as cattle (Bos taurus), horses (Equus ferus), donkeys (E. asinus), and sometimes goats (Capra hircus) will collapse petrel nest burrows by treading on them, causing loss of the contents and nest site.

Introduced plants also threaten the petrel nests. Introduced blackberries (Rubus spp.) grow rapidly and thickly, and can overgrow nest burrow entrances in the nonbreeding season, making the nest inaccessible to the returning petrels. Introduced red cinchona (Cinchona pubescens), a low-stature tree, grows thickly and creates root networks that the petrels cannot penetrate when excavating nest burrows, rendering large areas unusable to the petrels for nesting.

To address some of the issues around conservation of the species, a workshop was held in 2019 to develop a Conservation Action Plan for the Galapagos Petrel. Our project was carried out in 2021 to implement some of the strategies to work on protection and enhancement of petrel nesting areas developed in the Action Plan. Our objectives were:

- Develop methods to monitor petrel nests on private lands.

- Evaluate the knowledge of farmers and landowner knowledge as well as the attitude towards petrel conservation on Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal islands.

- Provide information and guidance for protecting petrel burrows.

- Monitor a set of petrel nest burrows on private lands to determine predation.

- Trial artificial burrows to increase nest site availability and replace nests lost to livestock trampling.

Nest Mapping

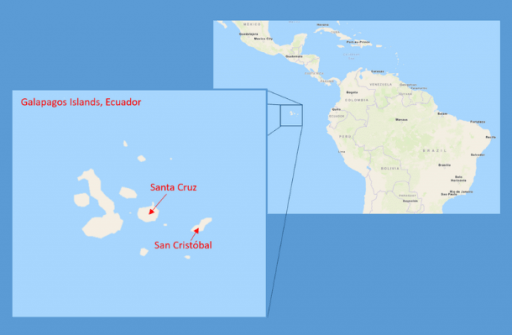

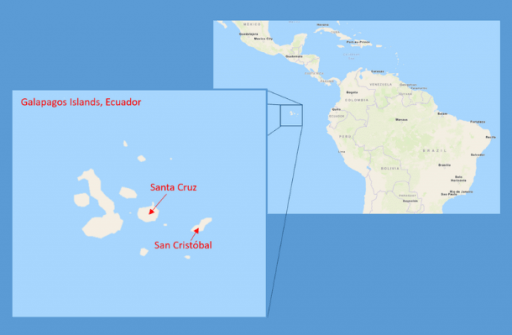

- Figure 1. The Galapagos Archipelago. The project was carried out in the agricultural highlands of Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal islands.

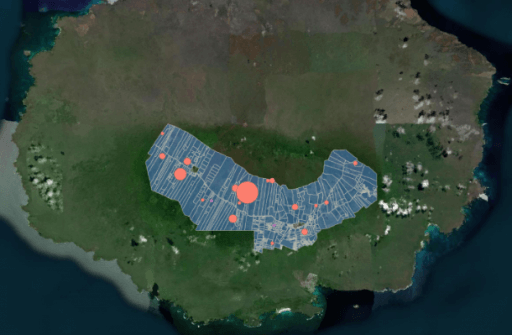

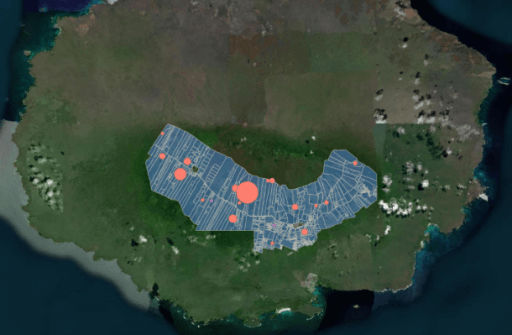

- Figure 2. Highlands of Santa Cruz Island. The agricultural zone is blue. Locations with petrel nests are orange circles; larger circles indicate more nests.

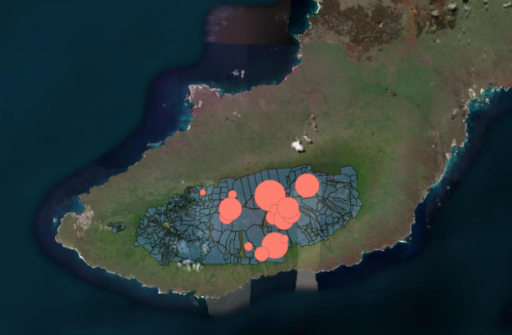

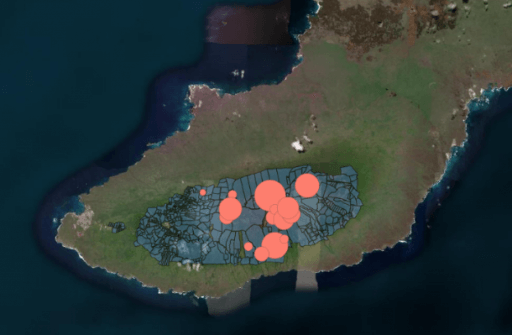

- Figure 3. Highlands of San Cristóbal Island. As in the previous map, the agricultural zone is blue. Locations with petrel nests are orange circles; larger circles indicate more nests.

We mapped out the locations of nests on private lands on Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal islands (Figures 1, 2, and 3). This was based on interviews with farmers and landowners about whether they thought there were nests on their properties, with follow-up to confirm and locate actual nest burrows.

Interviews and Outreach

Petrel nests were found on the properties of 17 landowners on Santa Cruz Island and 16 on San Cristóbal Island. During interviews, all of these landowners (100%) expressed interest in helping with petrel conservation on their lands. These landowners were contacted three times during the year for three interviews/interactions, each lasting about 10 to 15 minutes (initial/prior to nesting season; during nesting season providing outreach materials; and exit/post-breeding season). Landowners that expressed interest in maintaining and protecting the petrel nests on their property were provided with handouts about ways to protect petrels by season (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Handout provided to landowners, showing conservation actions they could take to protect petrels and petrel nests, by season.

Nest Monitoring

Figure 5. Galapagos Petrel in burrow on San Cristóbal Island.

Nest monitoring using burrowscopes (video cameras using a flexible fiber-optic cable to peer into natural burrows) showed occupied nests (Figure 5).

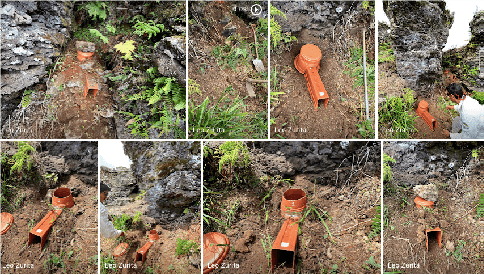

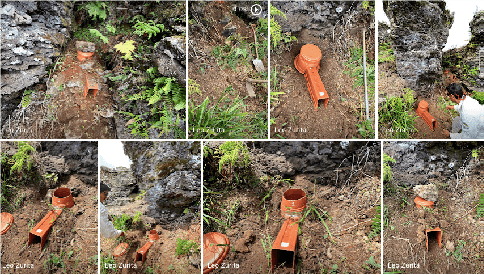

Figure 6. Artificial burrow construction on San Cristóbal Island.

Six artificial nests were built using plastic gardening materials (flower pots and drain channels) — three on San Cristobal and three on Santa Cruz Island (Figure 6). One artificial burrow on Santa Cruz Island was constructed at the exact same place where a natural burrow had been damaged and collapsed, in hopes that the breeding pair would occupy it. Two more artificial burrows were installed in the vicinity of this original nest.

Trail cameras showed petrels visiting and entering the artificial burrows, and also identified predators investigating the same burrows (Figures 7-9). Predators include rats and dogs.

- Figure 7A. Galapagos Petrel investigating and entering an artificial burrow on Santa Cruz Island.

- Figure 7B. Galapagos Petrel in an artificial burrow on Santa Cruz Island.

- Figure 8. Rat, probably Black Rat (Rattus rattus), investigating an artificial nest burrow.

- Figure 9. Dog investigating an artificial nest burrow on Santa Cruz Island.

Only the artificial burrow that replaced the collapsed burrow was occupied successfully. The breeding pair carried out some modifications, deepening the floor of the nest. An egg was detected in August of 2021. Following this, the nest was constantly monitored with camera traps. We placed rat poison baits (Brodifacoum) and a Goodnature A24 trap near the nest to control rodents and predators in the vicinity. The petrel chick successfully fledged in December 2021 (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Galapagos Petrel chick hatched in artificial nest burrow on Santa Cruz Island, September 2021.

We believe that artificial burrows can provide a stable and protective nest for Galapagos Petrels and thus aid in their conservation. They can also make monitoring and data gathering easier and more effective for researchers and Galapagos National Park rangers, by providing safe access to the chick via the removable top. Most farm owners are willing to collaborate with the project by accepting visits and monitoring of nests on their property. There is interest in controlling introduced species around nests and understanding of the value of these actions.

Acknowledgments: We thank the David and Lucille Packard Foundation for support of this project, the Galapagos National Park Service for support, and the landowners for allowing us to carry out the research activities.

Conservación del Petrel de Galápagos en Terrenos Privados

Las aves marinas del orden Procellariiformes pertenecen al grupo de aves más amenazadas del mundo. La disminución de sus poblaciones refleja amenazas marinas y terrestres. El Petrel de Galápagos o Patapegada (Pterodroma phaeopygia) es un ave marina que se reproduce solamente en el Archipiélago de Galápagos. Las amenazas marinas al petrel incluyen la captura incidental en artes de pesca, derrames de petróleo, y perdida de sus fuentes de comida resultado de la sobrepesca. En tierra, los petreles enfrentan amenazas de depredadores introducidos sobre sus huevos, pichones y adultos; la destrucción de los nidos madrigueras a través de pisoteo por animales domésticos, y perdida de hábitat a través de su conversión en agricultura o plantas introducidas.

Las especies introducidas que afectan el Petrel de Galápagos en tierra durante la estación reproductiva son perros (Canis familiaris), gatos (Felis catus), cerdos (Sus scrofa), y ratas (Rattus spp.). Todas esas especies comen los huevos, pichones, y de vez en cuando, adultos del petrel. Animales domésticos tales como ganado (Bos taurus), caballos (Equus ferus), burros (E. asinus), y a veces cabras (Capra hircus) pueden colapsar las madrigueras pisoteándolas, causando pérdida del contenido del nido y de la madriguera misma.

Plantas introducidas también amenazan las madrigueras de los petreles. La mora introducida (Rubus spp.) crece rápidamente y densamente, y puede cubrir las entradas a las madrigueras en la estación no reproductiva, haciendo inaccesible la madriguera a los petreles cuando retornan. La Cinchona roja (Cinchcona pubescens), otra planta introducida, crece densamente y forma redes densas que evitan que los petreles pueden excavar una madriguera, excluyendo los petreles de áreas grandes.

Para tratar algunos de problemas alrededor de la conservación de la especie, se realizó un taller en 2019 para desarrollar un Plan de Acción para la Conservación del Petrel de Galápagos. Nuestro proyecto se realizó en 2021 para iniciar la implementación de algunas estrategias del Plan para la protección y mejoramiento de áreas de anidación de los petreles. Nuestros objetivos fueron:

- Desarrollar métodos de monitoreo de nidos de petreles en propiedades privadas.

- Medir el nivel de conocimiento y actitud de los propietarios hacia la conservación del petrel en las islas Santa Cruz y San Cristóbal.

- Proveer información para protección de las madrigueras.

- Monitorear madrigueras de petreles en propiedades privadas para determinar las causas de depredación.

- Probar uso de madrigueras artificiales para aumentar disponibilidad de sitios para nidos y reemplazar madrigueras perdidas por pisoteo de animales domésticos.

Mapificación de Nidos

- Figura 1. El Archipiélago de Galápagos. El proyecto se realiza en las zonas agrícolas de las partes altas de las islas Santa Cruz y San Cristóbal.

- Figura 2. La parte alta de Isla Santa Cruz. La zona agrícola esta en azul claro. Lugares con nidos de petreles con círculos rojos; el tamaño del circulo indica el número relativo de nidos.

- Figura 3. La parte alta de Isla San Cristóbal. La zona agrícola esta en azul claro. Los lugares con nidos de petreles con círculos rojos; el tamaño del circulo indica número relativo de nidos.

Preparamos mapas de los lugares con presencia de nidos de petrel en propiedades privadas en las islas Santa Cruz y San Cristóbal (Figuras 1, 2 y 3), a base de entrevistas con los propietarios sobre su conocimiento de presencia de nidos en sus terrenos, con seguimiento para confirmar y marcar con GPS las madrigueras.

Entrevistas y Divulgación

Se encontró nidos de petreles en 17 propiedades en la Isla Santa Cruz y 16 en San Cristóbal. Durante las entrevistas, todos los propietarios (100%) expresaron interés en apoyando la conservación de los petreles en sus terrenos. Se contactó estos propietarios tres veces a través del año para tres entrevistas/interacciones, cada uno 10-15 minutos (inicial/antes de la estación reproductiva; durante la estación reproductiva proveyendo materiales de guía; final/pos-estación reproductiva). Los propietarios que expresaron interés en protección de las madrigueras en sus terrenos fueron provistos con folletos de información sobre las maneras efectivas para proteger a los petreles de acuerdo a la temporada de anidación y migración (Figura 4).

Figura 4. Afiche proveído a los propietarios, indicando acciones de conservación pueden realizar para la protección de los petreles y sus nidos, por estación.

Monitoreo de Nidos

Figura 5. Petrel de Galápagos en la madriguera en la Isla San Cristóbal.

Monitoreo de los nidos usando burrowscopes (cámaras video con un cable fibra óptica para ver dentro de las madrigueras) indicaban nidos ocupados (Figura 5).

Figura 6. Construcción de madrigueras artificiales en Isla San Cristóbal.

Se construyó seis madrigueras artificiales usando materiales plásticos disponibles en las islas (macetas y canales para drenaje), tres en San Cristóbal y tres en Santa Cruz (Figura 6). Una madriguera artificial en Santa Cruz se construyó en el lugar donde una madriguera natural fue dañada y derrumbada, con esperanzas que la pareja ocupara el nuevo espacio construido. Dos más se instalaron cerca el nido original.

Las cámaras trampa mostraron petreles visitando y entrando a las madrigueras artificiales, y también predadores investigando las mismas madrigueras (Figuras 7-9). Predadores incluyeron ratas y perros.

- Figura 7A. Petrel de Galápagos investigando y entrando una madriguera artificial en Isla Santa Cruz.

- Figura 7B. Petrel de Galápagos investigando y entrando una madriguera artificial en Isla Santa Cruz.

- Figura 8. Rata probablemente rata negra Rattus rattus, investigando una madriguera artificial.

- Figura 9. Perro investigando una madriguera artificial en Isla Santa Cruz.

La madriguera artificial que reemplazó la madriguera natural derrumbada fue la única ocupada exitosamente. La pareja hizo algunas modificaciones, haciendo más profundo el suelo del nido. Se detectó un hueveo en agosto 2021. A continuación, se monitoreó el nido constantemente, con cámaras trampa. Pusimos veneno para control de ratas (Brodifacoum) y una trampa Goodnature A24 cerca el nido para controlar predadores en el área. El pichón del petrel salió del nido en diciembre 2021 (Figura 10).

Figura 10. Petrel de Galápagos que eclosionó en una madriguera artificial en Isla Santa Cruz, septiembre 2021.

Las madrigueras artificiales pueden proveer un nido estable y protector para los Petreles de Galápagos y así apoyar su conservación. También, pueden hacer más fácil y eficaz el monitoreo y recolección de datos para investigadores y guardaparques de Parque Nacional Galápagos, por permitir acceso seguro y rápido al pichón a través de la tapa removible. La mayoría de los propietarios están dispuestos a colaborar con el proyecto, aceptando visitas y monitoreo de nidos en sus propiedades. Existe interés por los propietarios en controlar especies introducidas alrededor de los nidos, y entienden el valor de esas acciones.

Reconocimientos: Agradecemos a la Fundación David y Lucille Packard para apoya del Proyecto, al Directorio del Parque Nacional Galápagos por su apoyo, y a los propietarios para permitiéndonos realizar las investigaciones en sus propiedades.

###

American Bird Conservancy is a nonprofit organization dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. With an emphasis on achieving results and working in partnership, we take on the greatest problems facing birds today, innovating and building on rapid advancements in science to halt extinctions, protect habitats, eliminate threats, and build capacity for bird conservation. Find us on abcbirds.org, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (@ABCbirds).

Media Contact: Jordan Rutter, Director of Public Relations| jerutter@abcbirds.org | @JERutter

Expert Contacts: Carolina Proaño (carolina.bps@gmail.com; Tierramar Research Group)

Jonathan Guillén and Leo Zurita Arthos (Universidad San Francisco de Quito; lzurita@usfq.edu.ec, @leozurita)

David Wiedenfeld (American Bird Conservancy; dwiedenfeld@abcbirds,org)