Maui Parrotbill Getting Help on the Ground and From the Air

|

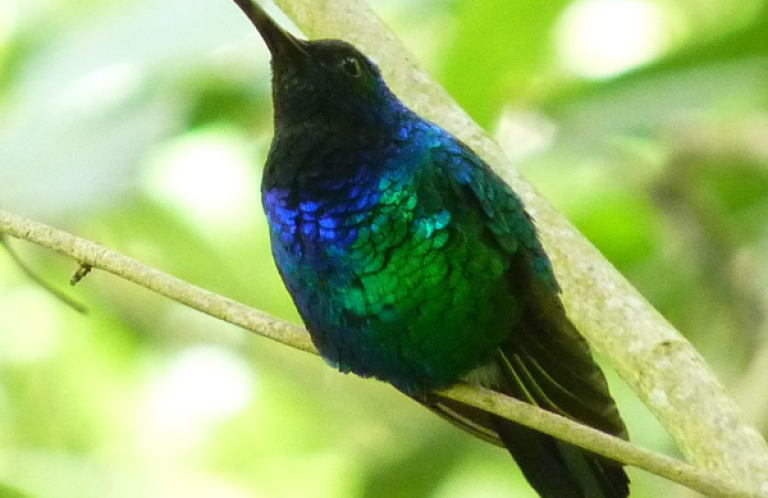

| Maui Parrotbill by Jack Jefferey |

(Washington, D.C.,

Hawaiian Airlines recently added Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project (MFBRP – a major force in the efforts to conserve the Maui Parrotbill) to their “Give Wings to Great Causes” flyer miles donation program for 2012. Patrons of Hawaiian Airlines can now donate frequent flyer miles to MFBRP, allowing staff to attend important inter-island collaboration events.

“Donated miles will help get MFBRP biologists to scientific meetings, training events, and conferences, as well as bring additional scientific expertise to Maui. This kind of support is extremely important to helping us fight the myriad of threats the Maui Parrotbill faces,” said Hanna Mounce, Project Coordinator and Avian Conservation Research Facilitator for MFBRP.

Mounce says that one of the most serious threats is climate change and its effects on non-native diseases. Avian malaria is the most deadly of these diseases with a single bite from an infected mosquito capable of killing some Hawaiian honeycreepers in as few as 72 hours. Mosquitoes carrying avian malaria are limited by cool temperatures so that forests above 5,000 feet are either disease-free or have only seasonal transmission. Climate change, however, is expected to reduce the size of these mosquito-free zones as warmer temperatures move gradually to higher and higher elevations.

MFBRP and partners that include the state Division of Forestry and Wildlife and American Bird Conservancy (ABC), a leading bird conservation group in the U.S., are initiating a landscape-scale ungulate-proof fencing project to restore and protect key habitat, including high elevation, drier lands on the leeward side of east Maui that were once important habitat of the Maui Parrotbill. These include the Nakula Natural Area Reserve and the Kahikinui Forest Reserve on the leeward side of east Maui that have been degraded by years of grazing by non-native goats, cows, and pigs. Once these areas are fenced, non-native ungulates will be removed and habitat restoration will be initiated. Habitat adjacent to these areas is being protected by private and public landowners under the auspices of the Leeward Haleakalā Watershed Restoration Partnership.

“If this species is going to persist, the availability of suitable habitat needs to be increased. With only 450 of these birds left, and with the many threats they face, there is no question that we are indeed in a race against time to save this bird,” said Dr. George Wallace, Vice President for Oceans and Islands at ABC.

Despite the fact that the lands targeted for restoration have been severely degraded by non-native cattle and goats for well over a century, natural regeneration of some plant species is expected to occur once the ungulates are removed. Active restoration of important parrotbill food plants also will be undertaken.

Following this habitat restoration, conservationists will attempt a critical recovery action – establishing a second population of the parrotbill. By providing additional habitat, it is hoped that a new, translocated population of wild and captive-reared parrotbill will thrive in this drier habitat where harsh weather conditions are less frequent compared to the windward side of the island.

Known as Kiwikiu in Hawaiian, the Maui Parrotbill is a 5.5-inch long insectivorous honeycreeper that has had most of its preferred habitat converted to agriculture by Polynesians and destroyed by non-native ungulates brought by Europeans. Currently, the remaining 450 parrotbill are restricted to a 15-square mile area of the windward side of east Maui. Although its low fecundity – typical clutch size is one egg – complicates its recovery, within existing suitable habitat, adults, with established home ranges, have high survival, with some being at least 15 years old. Natural history studies of the species only began in the 1980s, and the first parrotbill nest was not discovered until 1993. This bird uses its large, parrot-like bill to pluck and bite open fruit, lift bark and lichens, and rip open branches and stems in search of invertebrates. Since the chicks remain dependent on the parents for five months or longer, it is often sighted in family groups.

While Hawaiʻi is known for its beaches and lush, tropical climate, it is also known as the bird extinction capital of the world. Since the arrival of Europeans to the Hawaiian Islands, 71 bird species have become extinct out of a total of 113 endemic species that existed at the time of first human colonization. Of the remaining 42, 32 are federally listed, and ten of those have not even been seen for up to 40 years.

In areas of Hawaiʻi where there has been aggressive conservation action to reduce threats to birds, populations have been stable or increasing, and new projects underway are also making a difference. For example, a predator-proof fence – the first of its kind in the United States – was recently constructed to keep predators out of seabird nesting habitat at Kaʻena Point on Oʻahu; a 52-mile fence to exclude mouflon sheep and goats from Palila habitat on Mauna Kea is under construction; and an initiative to create a second population of the endangered Millerbird on Laysan Island as insurance against the species’ extinction has so far been successful. ABC and MFBRP are actively working with state, federal, and NGO partners such as the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service and the State of Hawaiʻi to implement a variety of on-the-ground projects to overcome threats to Hawaiʻi’s rare species.

An increase in federal funding is key to reversing the current trends that are negatively impacting bird populations. Unfortunately, the resources directed to Hawaiʻi’s environmental problems are alarmingly low in proportion to their need. While Hawaiian birds comprise one third of all U.S. bird species listed under the Endangered Species Act, only 4.1% of funding for recovery of listed bird species is directed their way. The Hawaiian Airlines “Give Wings to Great Causes” flyer miles donation program is a much needed contribution to the cause of increasing support for bird conservation in Hawaiʻi.