About the American Crow

The American Crow is widespread in North America and, like the Blue Jay, is often maligned and misunderstood. In folklore, the crow is sometimes associated with witchcraft and evil, or is thought to signify misfortune and even death. One popular term for a group of crows is a "murder"! Often considered a pest, the bird's name is used in association with stuffed manikins and movie characters — scarecrows — meant to frighten the birds from crops. Other cultures appreciate the crow's intelligence and adaptability, portraying it as an ingenious trickster that can foresee the future, and that sometimes helps humankind.

Male and female American Crows look alike, with all-black plumage that has an iridescent purple sheen in direct light. Corvus, the first part of the American Crow's scientific name, simply means “crow,” and its species name brachyrhynchos means "short beak" — which is true only in comparison to its larger, similar-looking relative the Common Raven. The crow's beak is actually fairly large — almost 2 inches long — stout, and slightly hooked, with stiff bristles over the nostrils.

This common bird is an uncommonly intelligent survivor, able to cope with human pressures that have almost eradicated many bird species. Researchers trying to trap them for studies find that they are not easy to trick, and once caught are not normally fooled the same way twice. They deftly avoid cars on busy roads where these birds forage for carrion, and loiter around trash on pick-up days, poking at bags between rush hours.

In the summer of 1999, the West Nile virus, a virulent, mosquito-borne disease, reached the United States, first appearing in New York City. West Nile affects birds as well as people and is particularly lethal to crows and jays, with an almost 100-percent mortality rate. Thousands of American Crows died from the virus in the first few months after it appeared. Millions more succumbed as West Nile swept across North America.

Although the initial impact of West Nile virus on the American Crow was significant, numbers have started to bounce back. Scientists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, using data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey, found that West Nile virus became less lethal as it spread westward, and that crows in more diverse habitats were less likely to contract the virus. As of 2021, the American Crow seemed to be past what had seemed a potentially devastating hurdle.

Songs and Sounds

The most familiar call of the American Crow is a repeated "caw-caw." Different types of caws are used to alert other crows to predators, to declare territory, or while mobbing enemies such as hawks and owls. The American Crow also produces a variety of other sounds including rattles, coos, and clicks, sometimes strung together into a long, rambling "song." It also mimics other birds such as the Barred Owl, and can imitate cats, dogs, and even human voices!

Listen here:

(Audio: Thomas G. Graves, XC496356. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/496356. Eric DeFonso, XC104834. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/104834. Ed Pandolfino, XC639144. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/639144.)

Breeding and Feeding

American Crow couples form long-term pair bonds and often live in family groups made up of the male, female, and young from previous years. This cooperative breeding behavior has been observed in a range of bird species, from the Acorn Woodpecker to the now-extinct Passenger Pigeon.

Both male and female crows build their twig nest, often assisted by young birds from the previous year's nesting season. The young crows do not breed until they are at least two years old, and most wait until they are at least four, remaining with their parents instead and helping raise their younger relatives.

The nest is lined with pine needles, animal hair, weeds, grasses, and tree bark, and is usually well hidden in a thick evergreen tree. The female incubates, while the male brings her food. After the young hatch, their parents and older siblings work together to feed and protect them.

One reason for the American Crow's success is its omnivorous diet. It eats almost anything it can find, including vegetable matter such as seeds, fruit, and grains, and live prey such as mice, insects, fish, earthworms, clams, and turtles. It raids other birds' nests for their eggs and young and readily scavenges for carrion and garbage.

During the winter, the American Crow flies from roosting to feeding sites, sometimes as far as 40 miles each way. It usually forages on the ground, but will fly high to drop tough items such as shellfish and nuts onto rocks or paved roads to break them open. Like the Pinyon Jay, Steller's Jay, and other corvids, this resourceful bird stores excess food to retrieve when needed.

It may forage alone or in groups; if the latter, one crow always acts as a sentry, keeping watch for potential dangers. As a scavenger, predator, and prey, the crow plays natural roles in its habitats, despite its frequent reputation as simply a “pest.”

Region and Range

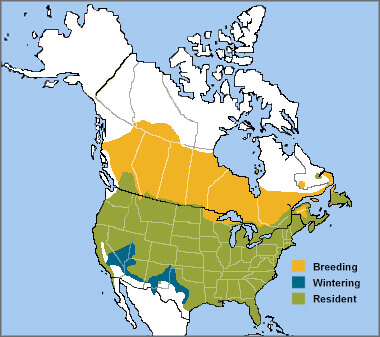

The American Crow has a wide range, from Canada throughout the continental United States. It is resident in the lower two-thirds of this area and along Canada's Atlantic coast. Across interior Canada, it is a breeding resident, joining brethren to the south during the harsh winter months.

During the winter, American Crows gather in large roosts each evening — sometimes in the hundreds of thousands. These corvid congregations provide warmth, shelter, and protection from nighttime predators such as the Great Horned Owl. Roosts are often located in suburban and even urban areas, where artificial lighting makes it possible for the crows to spot approaching threats, and where human-made structures provide extra shelter from the elements.

Researchers have found that these roosts also serve as information hubs: A study of Hooded Crows, a related Eurasian species, found that from roosts, some of the birds followed others on their daily commutes to learn new feeding areas. Such “intel” is especially important in winter, when food is scarce. Crow roosts break up at the beginning of the breeding season, usually around March.

Conservation of the American Crow

Although the American Crow is protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, there is a hunting season for the species in many states, as it is sometimes considered an agricultural pest. It may be included in permits for control, along with species such as the Red-winged Blackbird, Common Grackle, cowbirds, and magpies. This sometimes-controversial method of bird population control is employed when certain birds are deemed a threat to crops or livestock, or are concentrated in numbers considered to constitute a health hazard or nuisance.

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

ABC monitors bird control efforts, and sometimes joins partners in speaking out against unwarranted persecution of crows and other bird species.

Despite sporadic persecution, the American Crow — thanks in good part to its intelligence and adaptability — remains a common species in an increasingly human-altered world.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, have a huge impact on America's birds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds, bird habitat, and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Living a bird-friendly life can have an immediate impact on the birds around you. Doing so can be as easy as adding native plants to your garden, avoiding pesticides, and keeping cats indoors. To learn more, visit our Bird-Friendly Life page.

American Bird Conservancy and our Migratory Bird Joint Venture partners have improved conservation management on more than 6.4 million acres of U.S. bird habitat — an area larger than the state of Maryland — over the last ten years. This is a monumental undertaking, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.