About

The American White Pelican is an impressive bird in more ways than one. Its nine-foot wingspan is one of the largest of any North American bird, second only to the mighty California Condor. It's also one of the heaviest flying birds in the world, weighing up to 30 pounds. A flock of these pelicans on the water or soaring high against a blue sky is an impressive sight.

Both sexes of American White Pelicans look alike, with snow-white plumage set off by black wing feathers that are most noticeable in flight. Bill, legs and feet are pale orange. Juveniles are dusky white with pale yellow bills and feet.

Like many waterbirds such as the Great Egret, the American White Pelican becomes more colorful during its breeding season, with the bare skin around the eye, legs and feet changing to a vivid red-orange, and a light-yellow crest growing atop its head.

A more unusual feature of this species is the strange-looking “horn” or ridge that grows atop its upper bill during the breeding season.

Titillating Tubercles

The “horn” on the upper bill of an adult American White Pelican is a fibrous growth known as the nuptial tubercle. This odd growth develops in both sexes during the breeding season and is thought to contribute to its mating displays and perhaps signal breeding fitness. The nuptial tubercle frays and splits as the season goes on, and eventually sheds off, to regrow the next year.

Songs and Sounds

The adult American White Pelicans is a silent species, only giving low, grunting calls, usually heard at colony sites. The young are far noisier – even pelican embryos can emit loud squawks inside the egg in response to overheating or chilling. Groups of young make loud begging calls, raising a clamor that can be heard from a long distance away!

Listen to a variety of American White Pelican sounds here.

Breeding and Feeding

The American White Pelican is highly social and seasonally monogamous, pairing up quickly after arriving at their large colony sites, usually located on isolated lake or marsh islands. Courtship consists of circular flights over the colony, often in groups, and a variety of displays on the ground, including strutting, bowing, and head swaying.

A mated pair works to build their nest, a simple scrape on the ground, sometimes edged with a shallow rim of vegetation. Average clutch size is two eggs, and both adults share incubation duties for close to a month, warming the eggs under their large, webbed feet, a behavior that occurs only in pelicans and some pelican-like birds, such as Brown Booby and Brandt's Cormorant. The young hatch naked and blind, but their eyes open within a day, and they quickly develop a covering of white down.

Life in the nest is competitive and dangerous. Older nestlings often kill their younger siblings or push them out of the nest, particularly in times of food scarcity. This seemingly cruel behavior, called siblicide, has a practical purpose: If there is enough food, more chicks survive; if not, only the strongest make it to adulthood. Siblicide occurs in other birds such as the Great Horned Owl, Red-tailed Hawk, and Great Blue Heron.

Both pelican parents feed their young by regurgitating food. After several weeks, hatchlings leave the nest and congregate in large groups, known as pods or crèches. These groups provide protection from predators while parents are away foraging. Young pelicans leave the pod each day to return to the vicinity of their nest, where their parents continue to feed them. The young fledge after 2-3 months and leave the colony soon after.

Dipping for Dinner

Unlike the related Brown Pelican, which usually plunge-dives for food, the American White Pelican feeds on or just below the water's surface. Groups cooperate to drive prey into shallow water for easier capture, then feed in graceful, synchronized dipping maneuvers, sometimes completely encircling their prey while they feed.

Small fish, amphibians, and crayfish are favored food items, but this species is opportunistic, and will alter its diet in response to changing water levels or prey abundance. Migrating birds will readily forage at aquaculture farms.

Like the Bald Eagle, the American White Pelican is also a kleptoparasite, stealing food from other birds, including other pelicans and cormorants, when the opportunity presents itself.

Region and Range

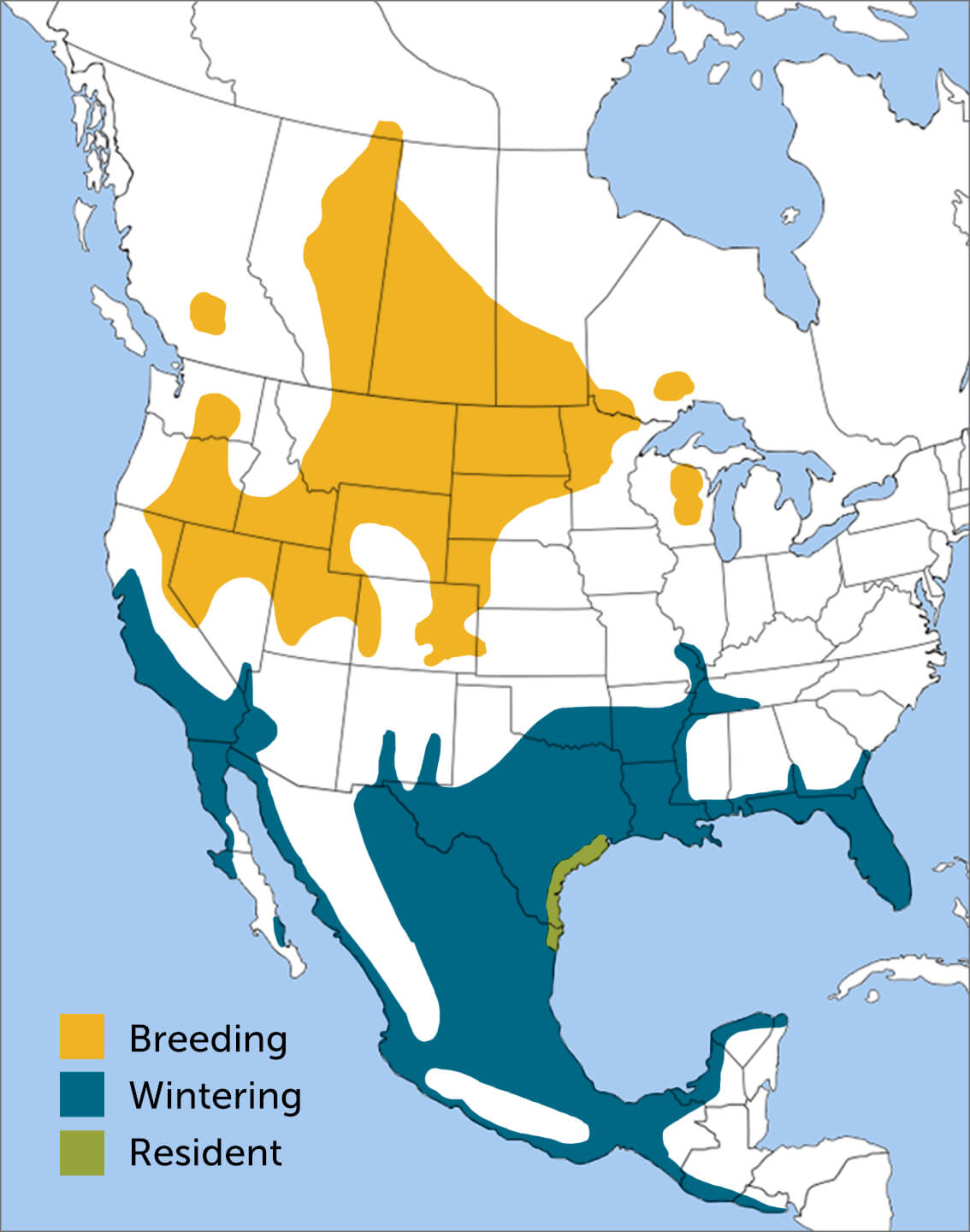

The American White Pelican nests in two fairly distinct populations. The first concentrates west of the Rocky Mountains in British Columbia, California, Nevada, Utah, and Idaho. These birds winter along the Pacific coast, from California south to Nicaragua.

The second population of American White Pelicans nests in the Canadian prairie provinces and upper Midwest states, migrating primarily southward and eastward towards the Gulf of Mexico.

American White Pelicans are daytime migrants, travelling in v-shaped flocks of up to several hundred birds. Like the Turkey Vulture and Swainson's Hawk, it takes advantage of energy-saving thermals as it flies. Non-migratory populations are resident in Texas and Mexico.

Conservation

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

American White Pelican populations declined by the mid-twentieth century due to overhunting and chemical pesticides such as DDT. Although these issues have been largely addressed, this species remains vulnerable to habitat loss on its foraging and breeding grounds. They may also be shot as pests at aquaculture farms.

The American White Pelican is especially sensitive to human disturbance and will abandon its eggs and young if a breeding colony is approached too closely.

In 2023, ABC joined partners in a lawsuit against Utah, charging that the state has diverted too much water from the Great Salt Lake and caused a significant drop in the lake's water levels, endangering birds such as the American White Pelican. The case continues; see the latest updates here.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies have a huge impact on seabirds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Plastics pose a deadly threat to seabirds around the world. You can help seabirds by reducing your daily use of plastics. To learn more and get started, visit our Plastics page.

American Bird Conservancy and partners are creating predator-free nest sites for vulnerable seabird species, reducing fishery impacts, and much more. This is a monumental undertaking, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.