Overview

About

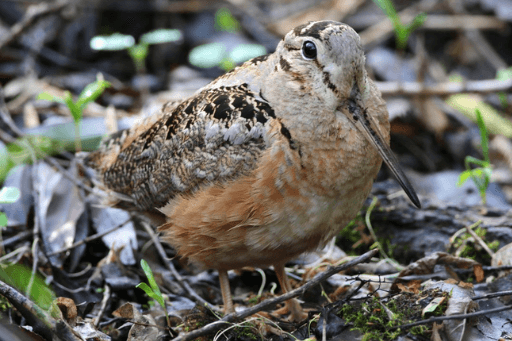

The plump, big-eyed, long-billed, and short-legged American Woodcock is an odd study in contrasts. Like the related Wilson’s Snipe, it’s a shorebird far from shore, often heard but rarely seen, and has earned colorful folk names such as “timberdoodle” and “bogsucker” through its unlikely habits and habitats. This strange, shy species is well worth seeking out, if only to observe the males’ enchanting flight display.

Woodcocks are best sought in late winter and early spring, in the crepuscular (twilight) hours of early morning or evening. The best places to look are in open fields adjoining hedgerows or forest edges. A patient, quiet observer does not have to wait very long for the show to begin! The male woodcock’s conspicuous flight displays, memorably dubbed “sky dances” by naturalist Aldo Leopold, begin with a series of nasal peent calls and transition into spiraling flights — a truly spectacular display.

Threats

Birds around the world are declining, and many of them are facing urgent, acute threats. But all birds, from the rarest species to familiar backyard birds, are made more vulnerable by the cumulative impacts of threats like habitat loss and collisions.

Habitat Loss

Habitat loss is a universal threat to birds. Habitat loss, along with the fragmentation and degradation of habitat, contributes to bird population declines of both very range-restricted species and long-distance migratory birds. Suitable habitat is the foundation of what birds need to thrive. Recent regional declines in American Woodcock numbers are often attributed to the loss of early-successional or second-growth habitat (the shrubby, grassy habitat that comes after a disturbance, like timber harvesting or fire), and to the conversion of habitat for agriculture or other development.

Glass Collisions

Because American Woodcocks are nocturnal migrants, they are frequent victims of collisions with glass windows, communications towers, and other human-made structures.

Pesticides & Toxins

A heavy diet of earthworms makes up more than half of the American Woodcock’s diet. This makes the American Woodcock vulnerable to poisoning by accumulated pesticides and heavy metals, which are picked up by the worms as they digest soil matter.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

Birds need our help to overcome the threats they face. At ABC, we’re inspired by the wonder of birds and driven by our responsibility to find solutions to meet their greatest challenges. With science as our foundation, and with inclusion and partnership at the heart of all we do, we take bold action for birds across the Americas.

Restoring Habitat

The American Woodcock shares its second-growth habitat with the Golden-winged Warbler and benefits from conservation measures designed for that vulnerable species. In Minnesota, with funding from the Outdoor Heritage Fund, ABC has improved more than 2,500 acres of habitat for American Woodcocks and Golden-winged Warblers.

Preventing Glass Collisions

ABC has been a leader in the effort to reduce the devastating toll of glass collisions on birds. We’ve developed innovative methods for evaluating the effectiveness of collision deterrents, created resources to elevate our collective understanding of collisions and make solutions readily accessible, and advocated for bird-friendly policies in the U.S.

Avoiding Pesticides & Toxins

ABC works with partners at the state and federal levels in the U.S. to call for the regulation or cancellation of the pesticides and toxins most harmful to birds. We develop innovative programs, like working directly with farmers to use neonicotinoid coating-free seeds, advance research into pesticides’ toll on birds, and encourage millions to pass on using harmful pesticides.

Bird Gallery

Rarely seen, the American Woodcock spends most of its time hidden in fields and forests, where its intricately patterned buff and brown plumage provides perfect camouflage. Its long, flexible bill can probe more than two inches underground in search of prey, and its large, dark eyes are positioned high and near the back of the skull, an adaptation that enables the woodcock to watch for danger as it feeds. Males and females look alike.

Sounds

On late winter and early spring evenings, male woodcocks perform conspicuous displays, dubbed “sky dances” by naturalist Aldo Leopold. A male begins by giving a buzzy, nasal peent call, turning in a tight circle while calling to broadcast to all nearby females.

Credit: Antonio Xeira, XC388694. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/388694.

Credit: Andrew Spencer, XC363105. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/363105.

Habitat

The American Woodcock is found year-round in a variety of forest types interspersed with open spaces with access to moist, organic soil for hunting earthworms.

- Breeds in young deciduous forests, favoring alder, aspen, and birch. Breeds near open areas such as agricultural fields, woodland edges, or abandoned farmland

- Spends the nonbreeding season in a wide variety of forests with understory gaps, including bottomland hardwoods, upland mixed pine-hardwoods, and mature longleaf pine

Range & Region

Specific Area

Southeastern Canada and the eastern United States

Range Detail

The American Woodcock breeds from Nova Scotia west to southern Manitoba and south through the eastern and central United States to northern Florida and eastern Texas. Its nonbreeding range, which overlaps with the southern portion of its breeding range, extends from Maryland west to southern Missouri and south through the Atlantic coastal states to northern Florida and eastern Texas.

Did you know?

The American Woodcock is the only member of its family native to North America, with seven other woodcock species occurring in Europe and Asia. It is a short-distance migrant, moving from the northernmost parts of its range to the Atlantic coast and Gulf states each fall.

Life History

The American Woodcock lives a largely nocturnal existence. It feeds under cover during the day during its breeding season, but forages at night throughout the year in open spaces such as fields, pastures, marsh edges, woodland openings, and even lawns.

Diet

Earthworms account for most of an American Woodcock’s diet. It will also feed on beetles, flies, centipedes, larvae, and occasionally seeds. A woodcock walks along the ground with a comical-looking rocking gait as it forages. The vibrations from its steps are thought to disturb earthworms underground, making them easier to detect and catch.

Courtship

The male begins his display with a buzzy, nasal peent call, turning in a tight circle while calling to broadcast to all nearby females. After a series of calls, he launches into the air, circling higher and higher until almost invisible, his wings making a distinctive chittering sound. At the apex of his display flight (200–350 feet), the male woodcock begins a series of high-pitched chirps, then tumbles back to earth in a steep, zig-zagging dive, where he begins his display anew.

Female woodcocks visit males’ display grounds and mate with them there, then leave to nest and raise the young by themselves, with males contributing no parental care. Some females visit multiple display grounds before nesting and even continue to visit while incubating and raising broods.

Nesting

A female woodcock nests on the ground within forest cover. Her nest, like an Eastern Whip-poor-will’s, is a shallow depression in the leaf litter or directly on the forest floor, where her cryptic plumage conceals her and the nest from predators.

Eggs & Young

American Woodcock clutch size averages four eggs, which the female incubates herself. The fluffy young hatch with eyes open and fully mobile, leaving the nest only hours after hatching. The mother will feed her young for about a week as they learn to find food. By about two weeks, the fledglings can fly short distances; they will spend another month foraging with their mother, then strike out on their own.