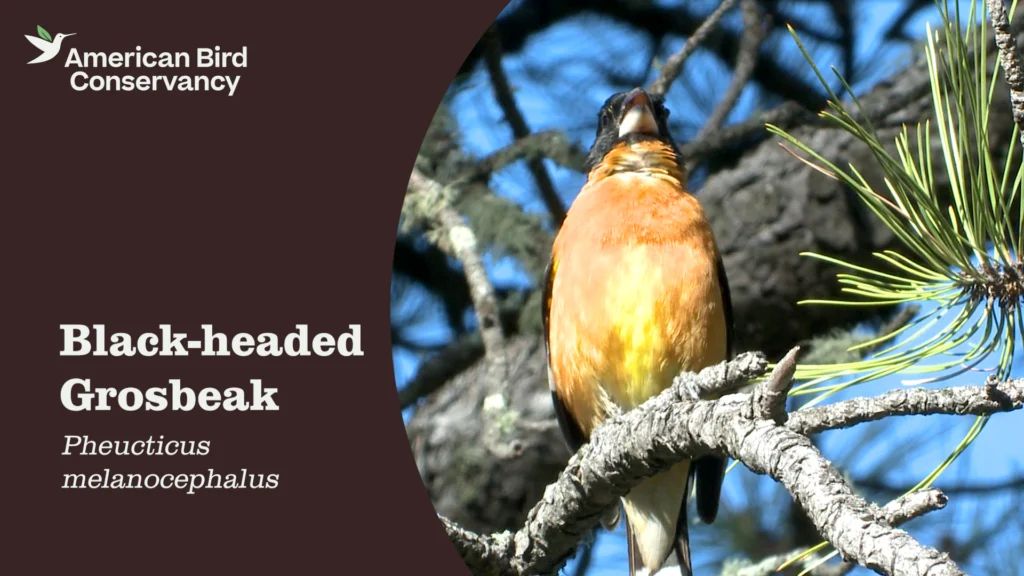

The Black-headed Grosbeak is a chunky, distinctive songbird. Found throughout western North America, its cheerful whistled song is reminiscent of the American Robin’s, and its notes herald the arrival of spring. The Black-headed Grosbeak is a bird of the forests, inhabiting woodland edges from subalpine forests to riparian zones in deserts, but also frequents backyards where it forages on sunflower seed feeders and even on nectar feeders.

The Black-headed Grosbeak shares the characteristic big beak of the Rose-breasted Grosbeak, its relative found in the eastern half of North America. This “gros” (big) beak is heavy and conical, perfect for cracking large seeds and hard-bodied insect prey.

Many Black-headed Grosbeaks migrate to the forests of central Mexico for the nonbreeding season, where huge roosts of migratory monarch butterflies also gather. The Black-headed Grosbeak is one of only a few species that can consume these butterflies, which are poisonous to most birds due to the high levels of toxins in their milkweed diet. Even with this relative immunity, the Black-headed Grosbeak can only feed on monarchs in roughly eight-day cycles, allowing its body to flush out the toxins in between bouts of feasting.