About the Double-crested Cormorant

The big, black Double-crested Cormorant is a common waterbird of lakes and shorelines throughout North America. Although it is an expert fisher, its feathers lack the waterproofing common to most other waterbirds, such as the Mallard or Common Loon. Unlike these waterbirds, Double-crested Cormorants don't have well-developed uropygial glands, which produce the waterproofing oil that birds spread over their feathers as they preen. Consequently, the Double-crested Cormorant has to spend a lot of time drying out, and it can often be sighted atop a piling, jetty, or dock with its waterlogged wings spread out to dry in the sun. This seeming disadvantage actually makes the cormorant a more efficient fish hunter, as its heavy bones and lack of buoyancy allow it to dive more easily and stay down for longer as it pursues its prey.

The Double-crested Cormorant is a black, long-necked waterbird with a long, hooked, orange bill. Juveniles are lighter, with paler necks and breasts. This species is roughly the size of a small goose, and like that bird, has strong webbed feet. Unlike geese and ducks, the cormorant's webbed feet show a totipalmate arrangement, meaning that all four toes are connected by webbing.

At first glance, the only color on a Double-crested Cormorant seems to be its yellowish-orange throat (gular) pouch and facial skin. However, a closer look reveals arresting aquamarine eyes, a bright blue mouth lining, and a glossy sheen to the body feathers. The double crests that give this cormorant its name are wispy black or white plumes, only visible during the breeding season.

There are five subspecies of Double-crested Cormorants told apart by body size and the color and shape of their crests.

A relative of birds such as the Great Frigatebird and Northern Gannet, the Double-crested Cormorant is the most numerous and widely distributed of the six North American cormorant species, which also include the Brandt's, Pelagic, Red-faced, Neotropic, and Great Cormorants. Cormorants are closely related to shags, which are smaller but similar-looking dark waterbirds distributed throughout Eurasia, Australasia, and Africa.

Songs and Sounds

The Double-crested Cormorant is generally a silent species, but gives deep, croaking calls at its breeding colonies and roosts.

Calls:

Calls:

Calls and flight calls:

Breeding and Feeding

Double-crested Cormorants are gregarious birds, gathering throughout the year in congregations that can number in the thousands. It favors small islands as colony sites, where it may occur alongside other colonial-nesting bird species such as the Great Blue Heron, Great Egret, Black-crowned Night Heron, and Royal Tern.

The Double-crested Cormorant is a master fisher, using strong webbed feet to kick its way underwater in pursuit of fish. It's an opportunistic feeder and has been recorded taking over 250 species of fish, which it captures with its hooked bill.

Most Double-crested Cormorants forage in shallow water less than 30 feet deep, close to the breeding colony and within sight of land. This species is rarely seen offshore.

The Double-crested Cormorant is monogamous during its nesting season. A male will choose a nest site in a tree or shrub, on a human-made structure such as a tower or bridge, or on the ground. There he advertises for a mate with a bowing, wing-waving display that shows off his head plumes, brightly colored throat pouch, and vivid eye. A mated pair will engage in recognition displays, where each bird will open its mouth to show the bright blue lining, stretch out its neck, and slowly move its head forward and upward while calling.

The male Double-crested Cormorant begins to bring material to the nest site while the female builds. She also must defend her nest from pirating neighbors who readily steal nest material if given the chance. The nest is a bulky platform of twigs, supplemented by other available materials such as seaweed, plastic trash, fishnets, rope, and even parts of dead birds. The nest lining is made from grass and rootlets. As the breeding season progresses, the nest becomes coated with guano, which strengthens the structure and holds it together. Nests may be reused from year to year.

The female Double-crested Cormorant may lay a clutch of one to seven white eggs; however, the average clutch size is three to four. Both parents incubate, balancing the eggs atop their webbed feet and covering them with their breast feathers. The eggs hatch in the order in which they were laid, in just short of one month. The nestlings are naked, blind, and helpless, but grow quickly with meals of regurgitated fish provided by both parents. The adults also provide water, pouring it from their mouths into those of their chicks.

The young cormorants begin to leave the nest at three to four weeks old. In breeding colonies where nests are on the ground, the young gather in large groups known as crèches, returning nightly to their nests to be fed. The young can fly at about six weeks, and are completely independent by 10 weeks of age. Double-crested Cormorants do not breed until they are at least two years old.

Region and Range

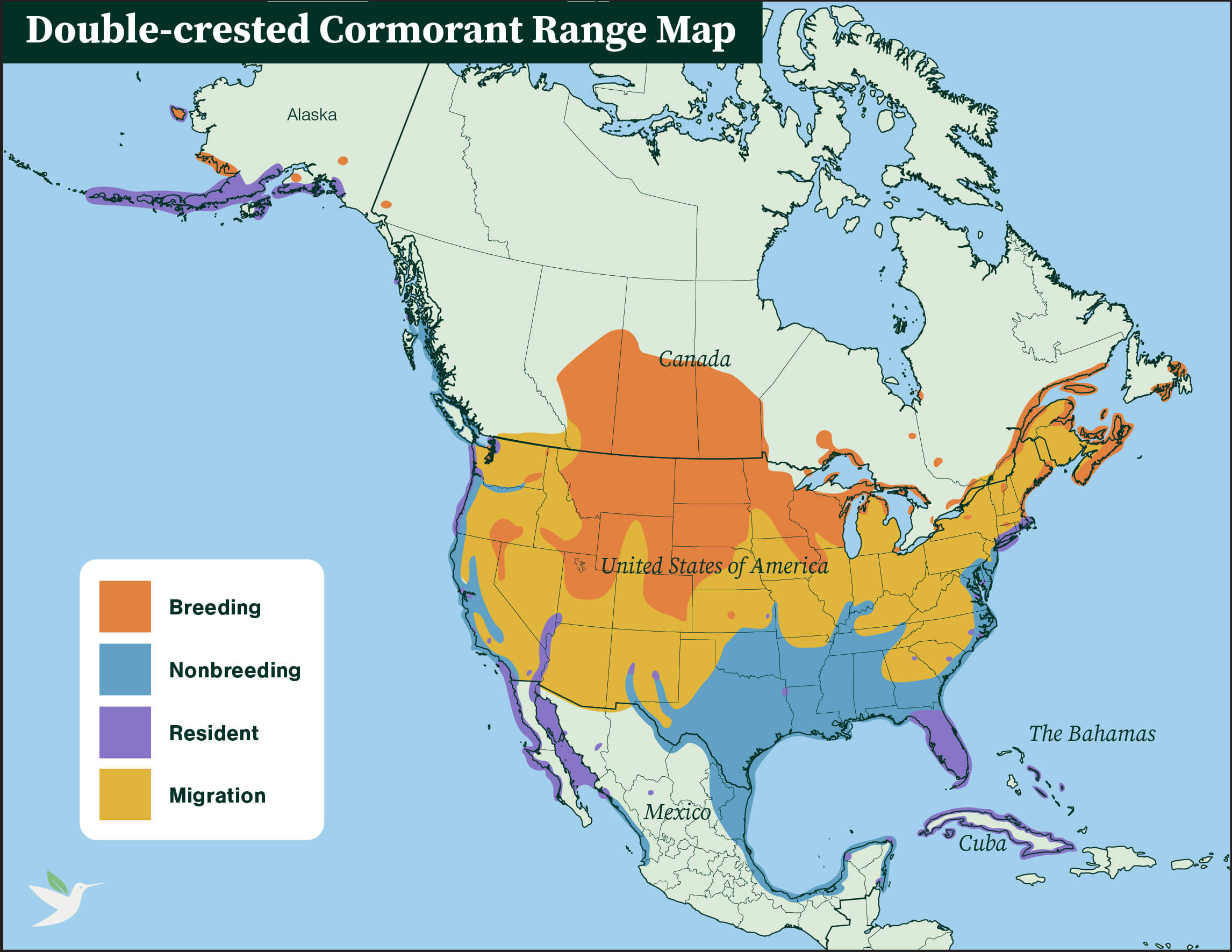

Double-crested Cormorants are widespread in North America. They can be found in Alaska; along the Pacific Coast from southern British Columbia to northern Mexico; in the Canadian and U.S. interior, where they are especially common on the Great Lakes; along the Atlantic Coast from Newfoundland to New York; and in Florida and the western Caribbean.

The Double-crested Cormorant has a variable migratory strategy, ranging from resident to medium-distance migration. Populations in the North American interior and along the northern Atlantic Coast migrate to the southern and southeastern U.S. coasts, and western populations migrate to the Pacific Coast. Populations in Florida, the Caribbean, the coastal Pacific Northwest, and coastal Mexico are year-round residents.

Conservation of the Double-crested Cormorant

The Double-crested Cormorant was once considered a species of concern because of steep population declines resulting from DDT use. Cormorant populations have rebounded since that toxin was banned, but now the species faces unnecessary persecution from humans who share their habitat, the threat of habitat loss, and ongoing risks from other pesticides and toxins.

Clearing and development of forested wetlands reduces available nesting and foraging habitats. This species is very sensitive to human activity at nesting colonies and will quickly abandon nests when disturbed, leaving eggs and chicks vulnerable to predation and overheating.

Double-crested Cormorants are top-flight fishers that congregate in areas where fish are abundant. Unfortunately, this sometimes leads them to commercial and sports fisheries as well as aquaculture facilities, and can bring them into unnecessary conflict with humans who perceive them as pests. Like many waterbirds, cormorants are sometimes killed or injured when they are caught on fishhooks and entangled in gillnets, fishing lines, lobster traps, or trawls.

Help support ABC's conservation mission!

Double-crested Cormorants quickly bioaccumulate toxic pesticides such as DDT from their all-fish diets, which led to drastic population declines in the late 1970s. Since DDT was banned, populations have rebounded but remain vulnerable to other contaminants such as oil spills.

Double-crested Cormorants are sometimes involved in collisions with aircraft, where their large size causes significant damage. This species fatally collides with powerlines as well.

Birds such as the Double-crested Cormorant need our help to overcome inaccurate assumptions and unnecessary persecution. ABC supports science-backed, nonlethal solutions to cormorant-human conflicts, while also working to address threats to the species from pesticides and fisheries bycatch.

ABC helps to reduce the impact of fisheries on seabirds by working directly with fishery managers to avoid inadvertently catching birds in their nets and on their lines. We also encourage increased consumer demand for sustainably harvested seafood.

ABC advocates for solutions to cormorant-aquaculture interactions that are rooted in science, use nonlethal means of managing cormorants when necessary, and also benefit aquaculture facilities. We have supported well-established and vetted programs such as those administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for managing cormorant-aquaculture interactions. Learn more about our policy and advocacy work and take action for birds like the Double-crested Cormorant.

ABC's policy team continues to push for better protections from the most harmful toxins to birds, advocating in individual states and the federal government, writing technical comments, submitting legal briefs, educating lawmakers, and writing op-eds.

Get Involved

Policies enacted by the U.S. Congress and federal agencies have a huge impact on seabirds. You can help shape these rules for the better by telling lawmakers to prioritize birds and bird-friendly measures. To get started, visit ABC's Action Center.

Plastics pose a deadly threat to seabirds around the world. You can help seabirds by reducing your daily use of plastics. To learn more and get started, visit our Plastics page.

American Bird Conservancy and partners are creating predator-free nest sites for vulnerable seabird species, reducing fishery impacts, and much more. This is a monumental undertaking, requiring the support of many, and you can help by making a gift today.