Overview

About

The enchanting, spiraling notes of a Veery’s liquid song recall long golden twilights in summer forests, shaded streams lined with ferns and wildflowers, and quiet woodland paths. A quick glimpse of this superlative singer reveals a plain, unassuming brown and white bird, a bit smaller than a Wood Thrush.

The Veery is a species of thrush belonging to a group of talented songsters that includes the Hermit, Swainson’s, Gray-cheeked, and Bicknell’s Thrushes. Their genus name, Catharus, derives from the Greek word katharos, which means “pure,” likely referring to the songs of this particularly tuneful group of birds.

The Veery was one of the favorite bird species of Rachel Carson, the scientist and nature writer whose groundbreaking book Silent Spring exposed the fatal effects of pesticides on the natural world, and birds in particular. Ms. Carson shared a love of this bird with her close friend, Dorothy Freeman, and the two often referred to the Veery in their letters to one another.

Threats

Long-distance migratory species like the Veery contend with the threat of habitat loss across the entire annual cycle, on the breeding and nonbreeding grounds and at stopover sites. All birds, from the rarest species to familiar backyard birds, are made more vulnerable by the cumulative impacts of threats like habitat loss and invasive species.

Habitat Loss

Forest loss and fragmentation are major threats at all stages of the Veery’s life cycle. The destruction of forests for agriculture, development, and dam-building are particular threats on its nonbreeding grounds in southern Brazil.

Wind Turbines

Veeries are often the victim of fatal collisions with a variety of human-made structures, including poorly sited wind turbines and communications towers. It does not collide with windows as frequently as it does other structures, but glass collisions are also a threat.

Cats & Invasive Species

Forest fragmentation allows Brown-headed Cowbirds to easily parasitize Veery nests and allows predators such as snakes, chipmunks, and outdoor cats easier access to nests as well. Overabundant white-tailed deer destroy the thick understory that Veeries need to breed successfully, and invasive plants replace native forest groundcover.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

Birds like the Veery need our help to overcome a range of threats. ABC is working with partners across the Americas to meet the variety of challenges facing birds.

We’re inspired by the wonder of birds and driven by our responsibility to find conservation solutions. With science as our foundation, and with inclusion and partnership at the heart of all we do, we take bold action for birds across the Americas.

Restoring Habitat

ABC works with U.S. partners to restore forest habitats and diversity, including enhancing the young, regenerating early-successional forests favored by Veeries and other declining bird species such as the Golden-winged Warbler.

Protecting Migration

ABC works on a landscape scale to conserve birds like the Veery, engaging dozens of partners throughout the Western Hemisphere to conserve priority habitats. We also improve habitats, including working lands, through innovative programs like BirdsPlus.

Rethinking Wind Turbines

If not sited properly, wind turbines can spell disaster for migrating birds. ABC’s science-backed approach to Bird-Smart wind energy identifies the most critical areas for birds and provides guidance to the wind industry to support safer wind solutions for birds.

Bird Gallery

Like the Wood Thrush, the Veery is a uniform reddish-brown above. It differs from that species by its plain buffy-white underside and grayish flanks, with minimal light brown spotting on its upper breast, while the Wood Thrush is heavily spotted below. The Veery’s long legs are light pink. Males and females look alike.

Bird Sounds

“The song of the Veery is one of the most magical and exquisite in the bird world. It is an ethereal downward spiral of flutey notes with an echoing, ventriloquial quality.”

– Frank Chapman, Bird Life (1897)

The Veery’s beautiful song is often given from a low and hidden perch. Its most common call is a harsh, descending veer, which gives this bird its name.

Credit: Ross Gallardy, XC325520. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/325520.

Credit: Molly Jacobson, XC484555. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/484555.

Credit: Frank Lambert, XC269179. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/269179.

Habitat

The Veery is a bird of the forest, through and through. It inhabits forests with dense understories on its breeding and nonbreeding grounds.

- Breeds in damp deciduous and mixed coniferous/deciduous second-growth woodlands with dense understory, usually near water

- May occur in a variety of woodland types including red maple swamps, spruce and fir forests, or alder/aspen woods

- Nests in moist, dense riparian thickets of alder, willow or cottonwood saplings along mountain waterways

Range & Region

Specific Area

North and South America

Range Detail

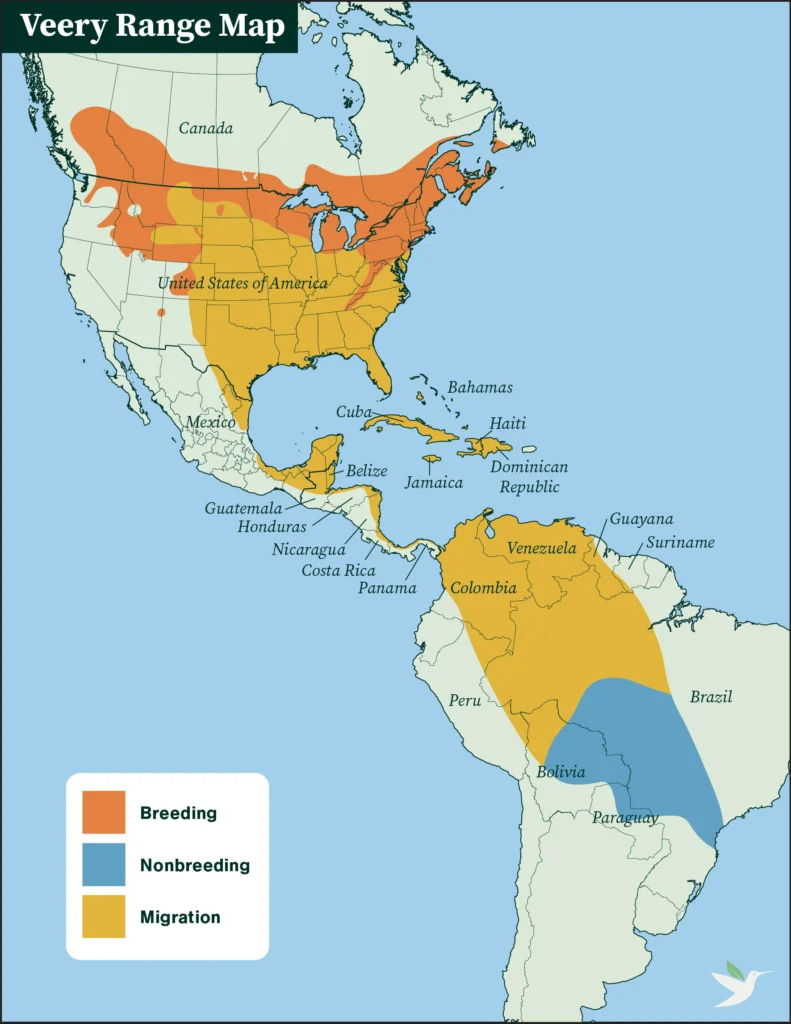

The Veery breeds across North America, from southern British Columbia east to Newfoundland and south to Arizona, South Dakota, Minnesota, New Jersey, and in the Appalachian Mountains south to northern Georgia. This thrush migrates to South America for the nonbreeding season, initially settling in Brazil’s lowland forests. Their migration takes them over the open waters of the Gulf and the Caribbean Sea.

Did you know?

Halfway through the nonbreeding season, Veeries make another, more widespread migration to additional sites in northern Brazil, southern Venezuela, Guyana, and Suriname. Some move south into Bolivia.

Life History

Veeries are at home in dense forests, where they are more often heard than seen. They hop, almost frog-like, along the ground as they feed and sing loudly from perches from the mid- to upper canopy. They fly quickly, maneuvering from perch to perch.

Diet

Insects and fruit make up much of the Veery’s diet, with a higher concentration of protein-rich insect prey during the breeding season. They primarily forage on the ground, sometimes gleaning through vegetation and flycatches. Sometimes Veeries will poke at decaying logs, and flip over leaves and stones, in search of insects. They take a variety of insects, including beetles, ants, bees, and grasshoppers, and eat wild cherry, blueberry, juneberry, elderberry. They’ve also been observed preying on frogs and salamanders.

Courtship

Male Veeries arrive on the breeding grounds first. Initially, they treat newly-arriving females as intruders and chase them away. Eventually the male’s aggressive chases turn into elaborate courtship flights, he accepts a female into his territory, and the two form a breeding pair.

Once considered monogamous, research has shown that Veeries of both sexes can have multiple mates, although males probably establish an initial pair bond with a one female. Even though a male will closely guard his mate as she nest-builds and broods, both sexes usually end up engaging in extra-pair copulations.

Nesting

The female Veery chooses a well-hidden nest site on or less than 5 feet from the ground. She then constructs a bulky, three-layer nest, first gathering an outer layer of large leaves, which serves as a nest platform, then weaving an inner cup of grapevine bark, weed stems, and other stringy material. She finishes her nest with an inner lining of rootlets and soft fungi.

Eggs & Young

An average Veery clutch numbers between three and five blue-green eggs. The female incubates alone for almost two weeks until hatching. Both parent birds feed the naked, blind chicks, which grow quickly and leave the nest in 10 to 12 days. Multiple male Veeries may father a clutch and help to feed the chicks, sometimes bringing food to multiple nests at the same time. Fledglings stay close to their parents for two more weeks before dispersing from their home territory.