Overview

About

The Western Kingbird, as its name implies, can be found across a wide area of the western United States and southern Canada. This colorful counterpart of the Eastern Kingbird is a member of the tyrant flycatcher family, a huge group of birds that includes species ranging from the fiery little Vermillion Flycatcher of the American Southwest to the Cock-tailed Tyrant, a resident of South American savannas.

Although many bird species were adversely impacted by the waves of European settlement that spread across North America, the Western Kingbird continued to survive and thrive — in fact, survey data show that their populations are increasing slightly across most of their nesting range.

European settlers altered native habitats as they expanded across the American West, cutting down forests in some places and planting trees in others. Increasingly sophisticated technology added utility poles, communications towers, windmills, and wires to the landscape.

The Western Kingbird’s breeding range expanded along with all this activity, as these human alterations inadvertently provided habitat for the bird. Human-made structures and planted trees on formerly open prairie provided more nesting and perching sites. In areas where forests were cleared, the Western Kingbird gained additional open habitat.

Threats

Even birds like the Western Kingbird that are experiencing population increases can be vulnerable to a variety of threats. Though Western Kingbirds are faring well as a result of human alteration of the landscape, their proximity to agricultural fields makes them more likely to be harmed by pesticides.

Pesticides & Toxins

Pesticides can take a heavy toll on birds in a variety of ways. Birds can be harmed by direct poisoning from pesticides, as well as lose insect prey to pesticides sprayed on crops.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

Avoiding Pesticides & Toxins

ABC works with partners at the state and federal levels in the U.S. to call for the regulation or cancellation of the pesticides and toxins most harmful to birds. We develop innovative programs, like working directly with farmers to use neonicotinoid coating-free seeds, advancing research into pesticides’ toll on birds, and encouraging millions to pass on using harmful pesticides.

Bird Gallery

The Western Kingbird is a large flycatcher, a bit bigger than an Eastern Kingbird. Males and females look alike, with a pale gray head, dark lores (the space between the eye and the base of the beak) and bill, and an indistinct white malar (throat) stripe. Its light gray breast blends into a yellow belly and undertail coverts (the feathers that serve as a transition between belly and tail), and the back is olive-green with darker wing coverts. The square-tipped tail is black with narrow white edges on the outer tail feathers. It has a reddish-orange central crown patch, only visible when the bird raises it — a cue that it’s agitated or on the defensive.

Bird Sounds

The Western Kingbird has a high, squeaky song sometimes described as pidik pik pidik PEEKado. Its shrill, sputtering call is a rising series of notes: widik pik widi pik pik. It also has a sharp, hard kit call.

Credit: Paul Marvin, XC752798. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/752798.

Credit: Paul Marvin, XC161768. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/161768.

Credit: Thomas Magarian, XC387633. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/387633.

Habitat

The abundant open habitats of western North America are the destination for breeding Western Kingbirds, which favor grasslands, desert shrub, cultivated fields, and other vast spaces dotted with prime perching spots.

- Found in open grasslands with scattered trees and shrubs to provide perches, including scrublands, sagebrush flats, open riparian corridors, pastures, and other open agricultural areas

- Readily inhabits open suburban and urban areas, using human-made structures such as buildings, utility poles, fence posts, antennas, and wires for perches and nesting spots

Range & Region

Specific Area

Western North America, Central America

Range Detail

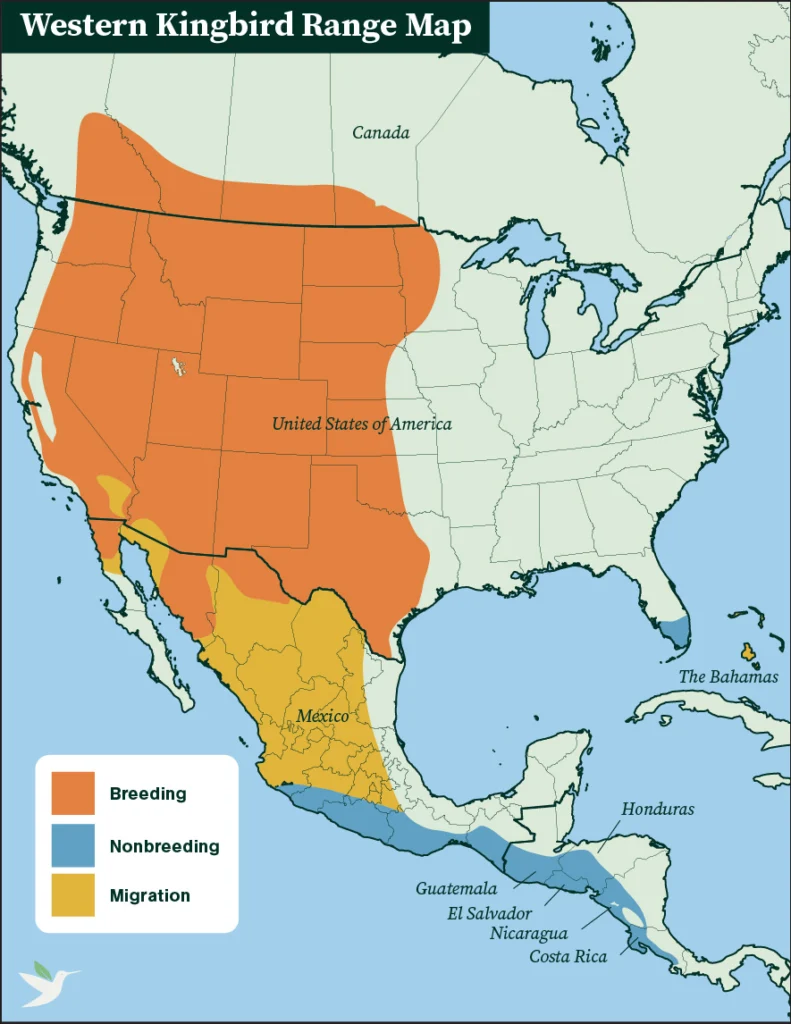

The Western Kingbird, true to its name, breeds from southwestern Canada down the Pacific Coast of the United States and east as far as Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas. Its breeding range extends south into Mexico. It migrates to nonbreeding areas in southern Mexico and Central America. Since the early 20th century, its nonbreeding range has expanded to southern Florida.

Did you know?

Fall migration is a two-step process for this species: Its first stop is in New Mexico, Arizona, and northern Mexico, where the birds complete their molt. From there, they migrate to their final nonbreeding destinations further south. During migration, they may gather in flocks of up to 200 birds.

Life History

Diet

Like other tyrant flycatchers, the Western Kingbird feeds chiefly on flying insects. It is an accomplished aerial hunter and feeder, snagging its prey mid-flight or pouncing upon it from a perch. It primarily takes bees, wasps, grasshoppers, crickets, beetles, ants, and flies, and will occasionally take small fruits.

Courtship

The male Western Kingbird usually returns to the breeding grounds first. He quickly establishes a territory, which he fiercely defends against other males. As part of his courtship repertoire, he performs a “tumble flight,” where he flies high, stalls, then quickly falls through the air, twisting, tumbling, and flipping while vocalizing. He returns to his original perch and starts the performance again. Courting males perform this unique flight at dawn and dusk. One performing male often spurs nearby rivals into their own courtship flights.

Nesting

The female Western Kingbird selects a mate and his territory soon after arriving on the breeding grounds. After mating, she builds the nest alone while the male guards their territory nearby. The nest is usually hidden within the tree canopy on a horizontal branch. In the absence of a suitable tree, she will nest on a human-made structure such as a utility pole. The nest is a bulky, cup-shaped structure of plant stems, grasses, twigs, and cottonwood bark and fiber, lined with softer materials including wool, hair, feathers, and bits of string or cloth.

Eggs & Young

The female Western Kingbird lays three to six (four on average) brown-spotted white eggs. She incubates the clutch herself for approximately two weeks, then broods the young for another 16 to 17 days until they fledge. Both parents feed the hatchlings, continuing after they leave the nest. The young birds remain in the vicinity of their nest and parents, who continue to protect and feed them. This species usually only raises one clutch per season.