Birds of Virginia: Grassland Birds

According to research published by ABC and other partners in 2019, grassland bird populations declined by 53 percent (more than 720 million birds) in the U.S. and Canada since 1970. These declines were steeper than those of boreal forest birds, eastern forest birds, coastal shorebirds, and aerial insectivores. The following three grassland birds offer a small taste of what to look for in Virginia, and some of the conservation efforts focused on these species.

This post is part of a five-part series in which we look at some of our favorite bird groups in Virginia (backyard birds, waterbirds, raptors, and forest birds) by profiling some of the most captivating species in each.

Grasshopper Sparrow

The Grasshopper Sparrow, a cryptically plumaged songbird of extensive grasslands, is present during the breeding season, when males advertise their territories with an insect-like trill of a song. Grasshopper Sparrows breed in grasslands across much of the lower 48 United States and into southern Canada, with isolated resident breeding populations in Florida, Central America, and the Caribbean. Most North American Grasshopper Sparrows migrate, wintering in the southern U.S., Mexico, the Caribbean, and Central America.

Locations: Grasshopper Sparrows can be found singing from large hayfields and pastures throughout much of Virginia in summer. Manassas National Battlefield is a protected grassland and reliable breeding area for this species in Northern Virginia. Most Grasshopper Sparrows leave Virginia in autumn, but eBird documents a few winter records.

Conservation: Grasshopper Sparrow populations in the U.S. and Canada declined 68 percent, to an estimated 31 million birds, between 1970 and 2014. In Virginia, conservationists at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and Piedmont Environmental Council are promoting best-management practices on grasslands within the Northern Virginia Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley BirdScape to benefit Grasshopper Sparrows and other grassland and early-successional species. In 2008, ABC co-published a guidebook for land managers in the Virginia Piedmont to promote management that benefits birds, including Grasshopper Sparrows, and other wildlife.

Outside Virginia, ABC also restores vast areas of grassland habitat for this and other bird species: In Texas and Oklahoma, ABC staff are working through Migratory Bird Joint Venture partnerships to restore 40,000 acres of habitat through the Grassland Restoration Incentive Program (GRIP) — for declining birds including the Grasshopper Sparrow, Eastern Meadowlark, Painted Bunting, and Northern Bobwhite, as well as Monarch butterflies. In the Chihuahuan grasslands of Mexico, ABC and our partner Pronatura Noreste have worked with local ranchers and communities to improve nearly 70,000 acres of habitat.

Short-eared Owl

Many owl species, like the Barred Owl, hunker down in dense forest, but not the Short-eared Owl. This is an open-area species, with its eastern populations nesting on Arctic tundra and migrating to Virginia and many other points south to spend the winter. There, this long-winged owl, with its “giant moth”-like flight, can be seen at dusk or dawn flying over agricultural fields, cattle pastures, and marshes to hunt voles, mice, and other small mammals.

Locations: Harrison Road is located near ABC's Virginia office in The Plains and is a great place to watch for Short-eared Owls as they hunt, flying over the fields or perching on fence posts across the field near sunset in the winter months.

Conservation: Short-eared Owl populations in the U.S. and Canada declined 65 percent, to an estimated 660,000 birds, between 1970 and 2014. In 2008, ABC co-published a guidebook for land managers in the Virginia Piedmont to promote management that benefits this species and other wildlife. (The Short-eared Owl is on the cover.) ABC also has advocated for better policies guiding rodenticide use to prevent accidental poisoning of owls and other nontarget wildlife, including an agreement to pull the most toxic of d-CON rodenticides from retail shelves in 2014.

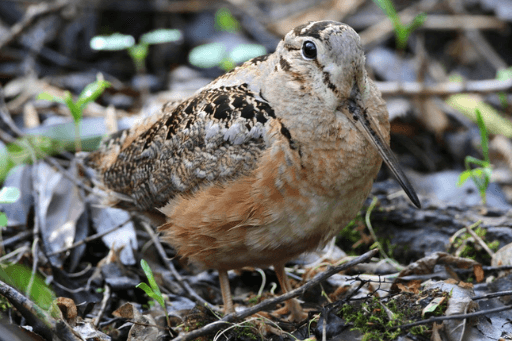

American Woodcock

Also known as the “timberdoodle,” the American Woodcock is a very unusual bird. It is technically a shorebird, but one that lives away from water. This species requires a habitat mosaic including both woodlands and grasslands. It walks with a bouncy gait and probes deeply with its long and sensitive bill in moist soil, seeking earthworms and other invertebrates. At dusk and after dark in late winter and spring, males display to attract females, making nasal “peent” calls from the ground before launching into an aerial flight performance with additional sounds produced by their feathers. They begin their display season much earlier than do most other birds, starting in December in some southern Virginia locations, and by late January in much of central and southern Virginia. Early March is prime display time in the northern part of the commonwealth.

Location: While the American Woodcock can be seen throughout the state, a quick reference to the second Virginia Breeding Bird Atlas eBird page for the species will show many breeding locations throughout the Coastal Plain, Piedmont, and Mountain-Valley ecoregions. These little football-shaped birds frequent open, tall-grass fields with small areas of short grass from which the males launch their aerial flights and then land to strut their stuff. Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, especially at the parking lot of the Woodland Trail, and Manassas National Battlefield, at the Featherbed Lane parking lot for the Deep Cut Trail, are two of many possible locations in Virginia to watch these birds.

Conservation: A multi-state migration tracking project is currently being implemented by the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources as part of the Eastern Woodcock Migration Research Cooperative. Using GPS satellite transmitters, the study is looking at timing and length of migration, survival, and stopover site use. Also in Virginia, conservationists at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and Piedmont Environmental Council are promoting best-management practices on grasslands within the Northern Virginia Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley BirdScape to benefit the American Woodcock, along with the Grasshopper Sparrow as mentioned above, and the 2008 guidebook ABC co-published for land managers in the Virginia Piedmont also promotes management that benefits woodcock.

Outside Virginia, in the Great Lakes region, much of the habitat management by ABC and our partners enhancing 14,000 acres for Golden-winged Warblers also benefits American Woodcock.

We hope you enjoyed this blog post about Virginia grassland birds. We recommend the following as additional resources for bird-watching information specific to Virginia:

- Virginia Bird & Wildlife Trail, an organized network of outdoor sites highlighting the best places to see birds and wildlife in the commonwealth.

- Second Virginia Breeding Bird Atlas (eBird Portal) ebird.org/atlasva/home (Note: A free eBird account is required to view these maps/data.)

- Virginia Society of Ornithology www.virginiabirds.org.

- Northern Virginia Bird Club www.nvabc.org.

- Birding Virginia for birding site information with profiles on birding hotspots and counties.

- A Birder's Guide to Virginia, by David W. Johnston, 1999, American Birding Association.

Authors

Daniel Lebbin, Vice President of Threatened Species, American Bird Conservancy; Sergio Harding, Nongame Bird Conservation Biologist, Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources; Ashley Peele, Avian Ecologist, Conservation Management Institute, Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation, Virginia Tech; Becky Keller, Science Coordinator, Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture, American Bird Conservancy; EJ Williams, Vice President, Southeast Region, American Bird Conservancy

Thanks also to Lindsey Troutman, Craig Watson, Ruth Boettcher, Kirsten Luke, Jeff Larkin, Jen Davis, Andrés Anchondo, Peter Dieser, David Wiedenfeld, George Wallace, and the Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture Team (Elizabeth Brewer, Amanda Duren, and Jessica Wise) for their suggestions and edits to this blog series.