Can Wind Energy Be Bird Safe?

Nearly every week, Kimberly Kaufman receives messages from birders and conservationists alerting her to new wind energy designs that bill themselves as safe for wildlife. The technologies come in all shapes and sizes and are in varying stages of development. Yet each claims to do one thing that conventional wind turbines can't: harness the incredible power of wind without killing birds.

American Tree Sparrows are one species among hundreds that are killed by wind turbines. Photo by Tania Thomson/Shutterstock

Kaufman, who is the Executive Director of Ohio's Black Swamp Bird Observatory, spends a sizable portion of her waking hours trying to raise awareness of the perils that traditional wind turbines—towering monopoles with blades that churn the air up to 175 miles an hour—pose for birds. So she's intrigued by the notion that entrepreneurs are dreaming up new ways to capture wind energy. And she appreciates that the Observatory's supporters are paying attention.

But she's also cautious. “If any of these designs are going to gain a foothold, we have to show that they are as efficient or at least close to the efficiency of the conventional design,” says Kaufman, who is also an ABC board member.

And the only way to know for sure if they're safe for birds is to build them and test them out, which raises an uncomfortable question: “Where do you decide you're going to experiment?”

The Deadly Design of Conventional Wind Energy

Conventional wind energy technology is treacherous for birds. A 2013 study published by the ornithologist K. Shawn Smallwood in The Wildlife Society Bulletin found that wind turbines killed an estimated 573,000 birds annually in the United States.

That figure may be conservative for several reasons: The country's wind capacity has since increased. Data on bird fatalities are typically collected not by independent third parties but by paid consultants to the wind industry. And dead birds are often hard to find—carried off by predators, or struck in such a way that they end up far from the turbine itself.

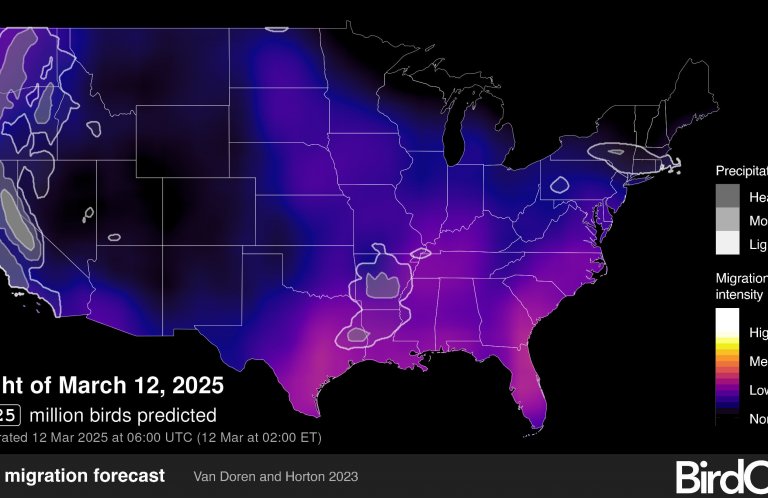

Fast-spinning blades of wind turbines are particularly dangerous to birds during spring and fall, when migrants take to the skies in billions. The wind industry has asserted that birds fly well above turbines' rotor blades. But research by federal scientists suggests otherwise: Earlier this year, a radar study along the shore of Lake Ontario by scientists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that birds fly at altitudes that place them squarely at risk of colliding with turbines.

Research by scientists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that birds fly at altitudes that place them squarely at risk of colliding with wind turbines. Image provided by SheerWind

It's a sobering pattern that plays out all over the country, as wind projects continue to jeopardize many bird species—some of them threatened or endangered. Among the worst are Texas's Gulf Wind, which sits within two critical migratory pathways and on habitat for grassland species such as Sprague's Pipit and Long-billed Curlew. Another is West Virginia's Laurel Mountain, where Wood Thrush and Golden-winged Warbler pass through or breed nearby.

Plans for new wind projects, meanwhile, have popped up in many other areas that are important for birds. They include Cape Wind, an offshore project in Nantucket Sound, an area with one of the highest concentrations of migratory birds in the world; and Nebraska's Ninnescah, which would feature a 66-mile-long power line traversing the migratory corridor of federally endangered Whooping Cranes.

With all of these projects—existing and proposed—much of the conflict between infrastructure and wildlife could be eliminated through better science and stricter regulation, says Dr. Michael Hutchins, Director of ABC's Bird-Smart Wind Energy Campaign. But there's another route, too, he says. “One of the best solutions,” Dr. Hutchins says, “would be bird- and bat-friendly wind energy technology.”

Entrepreneurs are trying to seize the opportunity. The resulting technologies are often otherworldly in their designs: a giant sail that funnels wind through a central turbine; a helium-filled airship outfitted with “fins” that generate electricity as the structures rotate; and a vertical mast mounted with an oscillating device meant to mimic the tilting tail of a humpback whale.

All of these new wind technologies still have a lot to prove, Hutchins says. Can they produce energy at a similar cost to traditional turbines? And can they prove they don't harm wildlife?

“If they can, then there will be no excuse for continuing to build and operate the bird- and bat-killing kind,” he says. But it's not as simple as developing technologies that are friendlier to wildlife, he adds. “Government regulators don't hold wind energy companies accountable for bird deaths, so they have no incentive to change.”

Taking a Different Approach with Wind

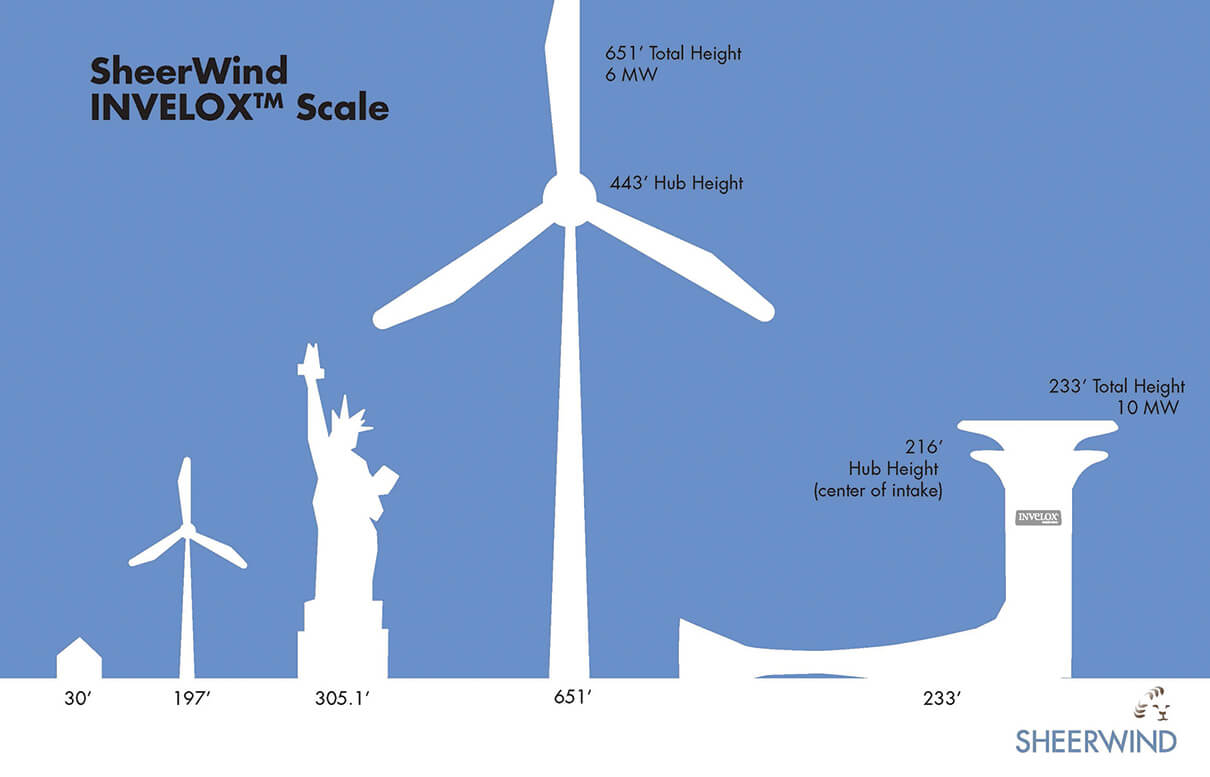

One of the new companies is SheerWind, whose Invelox technology harvests wind energy even in areas where airflow is minimal. Invelox captures wind by funneling it through tubes that “squeeze” the wind and increase its speed, much in the same way that putting one's finger over a garden hose will accelerate the flow of water. Then multiple turbines located inside the structure generate power from the magnified wind speed.

SheerWind's Invelox technology funnels wind through hourglass-shaped tunnels that can stand vertically or—as with this half-built installation on the Palmyra Atoll—run horizontal to the ground. Photo by Cindy Coker

Daryoush Allaei, the founder and Chief Executive Officer of SheerWind, first heard of wind energy's “bird issues” while researching traditional turbines' adverse effects on other creatures: humans. As he dug into the matter of noise and vibration, he discovered that bird fatalities were a major concern, too. So he got to thinking about different ways to harvest wind.

“The problem is that wind turbines are the only electromechanical system ever invented where the fuel is not controlled,” says Dr. Allaei, a mechanical engineer who has done research and development for the U.S. military for nearly 30 years. “Fuel in this case is wind. And when the fuel is not controlled, you have bird issues, noise issues, cost issues, efficiency problems. Invelox basically puts the fuel under control. When you do that, you solve all those issues.”

SheerWind says that its Invelox technology captures wind energy without harming birds. Photo provided by SheerWind

Dr. Allaei says one Invelox structure produces between two and a half and three times as much energy as one traditional turbine. He also says there are several reasons why the technology is safe for birds: the funnel-like structure has no rotating components on the outside; nets can be installed at the opening to prevent birds or bats from entering; and because the technique works just as well in low wind speeds, it doesn't need to be installed in windy corridors along or near birds' migratory pathways.

Invelox is currently operating at three locations: a test facility at SheerWind's corporate headquarters, in Chaska, Minn.; at the U.S. Army National Guard's Fort Custer, in Michigan; and on Palmyra Atoll, a tiny dot in the Pacific 1,000 miles south of Hawaii that is co-owned by The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Several more installations are being built, including sites in China, Denmark, the Netherlands, and New Zealand.

SheerWind does not systematically collect data on bird fatalities at its three existing wind facilities. But Dr. Allaei notes that every day, company employees inspect the Minnesota structure, which has been operational since 2012, and so far have only once encountered feathers—presumably from a pigeon that wandered into the funnel. Although the company has no data on birds from the Palmyra Atoll installation, it could be particularly instructive: Palmyra provides nesting habitat for more than one million seabirds.

The Palmyra Atoll is a tiny dot in the Pacific 1,000 miles south of Hawai'i that provides nesting habitat for more than a million seabirds, such as this Red-footed Booby. It is also the site of an Invelox wind energy installation. Photo by Cláudia Brasileiro Martins Kagiyama

Still, Dr. Allaei says he is optimistic that his technology doesn't harm birds. “We are bird-safe. We have no evidence otherwise,” he says. “Common sense tells me that birds are more equipped naturally to avoid a static structure than a rotating structure. So for that reason I think we have a better chance.”

A Need for Innovation—and Vigilance—in the Wind Energy Industry

Although he's cautiously optimistic about such new technologies, Hutchins says an absence of dead birds isn't the same as scientific proof that a technology is safe for wildlife. Empirical evidence through rigorous scientific testing is the only way to determine whether Invelox or any other approach is truly “bird-safe.”

He would also like to see the federal government devote greater financial support to research and development of alternative wind energy designs—especially those that seem most promising.

Cindy Margulis, Executive Director of Golden Gate Audubon Society, in California, thinks Silicon Valley could provide a boost, too. “In our patch of the nation, we recognize that the combination of incentives and exacting design constraints sometimes produces true innovation,” Margulis says. What if, she wonders, a wealthy benefactor were to underwrite a competition to design a new way of generating renewable energy that is 100 percent compatible with sustaining wildlife populations, and doesn't destroy existing habitats?

“Our wildlife populations would sure be well served if we could figure out how to produce renewable energy widely without adversely impacting wildlife and sensitive habitats,” Margulis says.

Until that happens, however, bird conservationists have their hands full with monitoring the current industry. For more than a decade, Golden Gate Audubon Society has pressed industry and government to stop the slaughter of wildlife at the Altamont Pass Wind Resource Area in Northern California, where at least 4,700 birds die every year—including 1,300 raptors—at Altamont's facilities.

Thousands of miles away, in northern Ohio, Kim Kaufman is fighting a similar battle. Two years ago, Black Swamp Bird Observatory petitioned two state agencies to release data on how many birds were dying at Blue Creek Wind Farm. The facility's parent company, Iberdrola, is now suing the agencies to keep the information private.

Conflicts like these make Kaufman circumspect about the new technologies. Regulation of the current wind energy industry is woefully inadequate, she says. “Once we develop a better regulatory framework, then we can start to talk about how to fit other designs into that framework.”

There are many lingering questions, she says. How would these alternative designs be regulated? What procedures and protocols would be necessary to monitor and evaluate them? How might they negatively affect birds in ways that are different from traditional wind turbines?

Addressing those questions will be crucial, she says, “So we're not looking back and saying, ‘We made the same mistakes we made with the conventional design.'”

Dr. Hutchins thinks the answers are within reach. “Bladed turbines are a 2,000-year-old technology,” he says. “We can do better.”

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the Winter 2016-2017 issue of Bird Conservation magazine, a benefit of membership with American Bird Conservancy.

Libby Sander is Senior Writer and Editor at American Bird Conservancy. Before coming to ABC in 2015, she spent 13 years as a journalist, writing news stories and award-winning features for The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. You can follow her on Twitter at @libsander.

Libby Sander is Senior Writer and Editor at American Bird Conservancy. Before coming to ABC in 2015, she spent 13 years as a journalist, writing news stories and award-winning features for The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. You can follow her on Twitter at @libsander.