California Urged to Ban Super-toxic Rat Poison

|

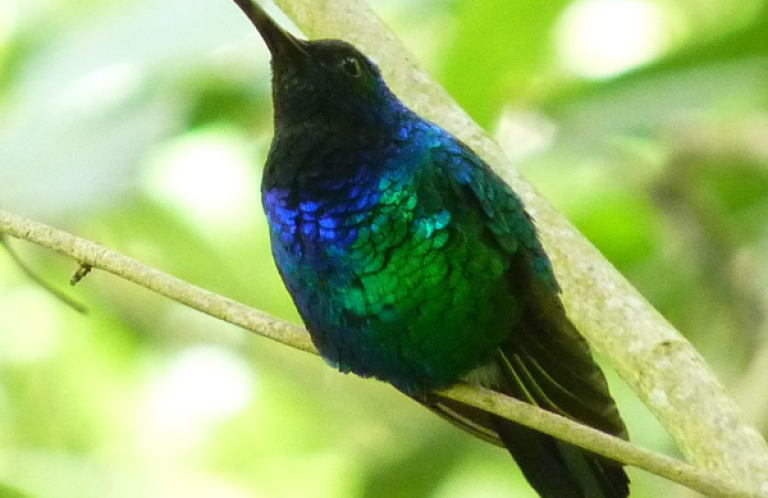

| Red-tailed Hawk by Owen Deutsch |

SAN FRANCISCO (December 11, 2012) A coalition of environmental and public-health groups called on the California Department of Pesticide Regulation on Monday to end the use of super-toxic rat poisons in the state. These highly toxic rodenticides — known as second-generation anticoagulants — have been linked to the poisonings of wildlife, pets and children. The groups' request, in comments submitted to the department, echoes concerns of state wildlife officials about the need to restrict these dangerous products.

“Super-toxic rat poisons are silent, indiscriminate killers,” said Jonathan Evans of the Center for Biological Diversity. “It's time to stop the bleeding and pull these poisons from the shelves.”

Anticoagulant rodenticides interfere with blood clotting, resulting in uncontrollable bleeding that leads to death. Second-generation anticoagulants — including brodifacoum, bromadiolone, difethialone and difenacoum — are especially hazardous and persist for a long time in body tissues. These slow-acting poisons are often eaten for several days by rats and mice, causing the toxins to accumulate to many times the lethal dose in their tissues. Predators or scavengers like hawks, owls, foxes and mountain lions that feed on poisoned rodents are then also poisoned.

“The sick and disoriented rodents become easy prey for a hungry raptor that can consume six mice in one night,” said Cynthia Palmer, pesticides program manager at the American Bird Conservancy. “By killing owls and hawks, those who use these secondary poisons are destroying nature's own rodent-control system.”

Harm to wildlife is widespread throughout the state. Researchers at the University of California found second-generation anticoagulants in 70 percent of mammals and 68 percent of the birds they examined. Officials at the California Department of Fish and Game have documented poisonings in numerous animals, including raptors (eagles, hawks, falcons and owls) and endangered San Joaquin kit foxes. Biologists with the National Park Service have also documented deaths and poisonings of mountain lions and bobcats in Southern California's Santa Monica Mountains. Even in remote areas of Northern California, research has revealed unacceptably high levels of poison in an endangered forest predator, the Pacific fisher: 75 percent of fishers tested showed rodenticide contamination.

“The state Department of Pesticide Regulation continues to allow use of these poisons despite overwhelming evidence that they're devastating our wildlife, including some protected by the Endangered Species Act,” said Greg Loarie, an Earthjustice attorney. “We just don't need these poisons; there are good alternatives already out there.”

Super-toxic rat poisons also pose a threat to children. Data from state pesticide regulators and the federal Environmental Protection Agency document that 12,000 to 15,000 children under age six are accidentally exposed to rat poisons each year across the country. The EPA says children in low-income families are disproportionately exposed to rat poisons.

“These super-toxic rat poisons are a completely unnecessary hazard when better, safer alternatives for rodent control exist to address current and future infestations,” said Sarah Aird, co-director of the statewide coalition Californians for Pesticide Reform. “The best fix for rodent problems is to address the underlying environmental and deficient housing conditions that give them access to food, water and shelter — what attracts them in the first place.”

Other safe alternatives exist to address rodent outbreaks in homes and rural areas. Effective measures include rodent proofing of homes and farms by sealing cracks and crevices and eliminating food sources; providing owl boxes to encourage natural predation; and utilizing traps that don't involve these highly toxic chemicals.

The California Department of Pesticide Regulation has ignored repeated requests to regulate these poisons, dating back to a 1999 request filed by the California Department of Fish and Game.

The groups were represented in comments by Earthjustice attorney Greg Loarie and experts with the Pesticide Research Institute.