Overview

About

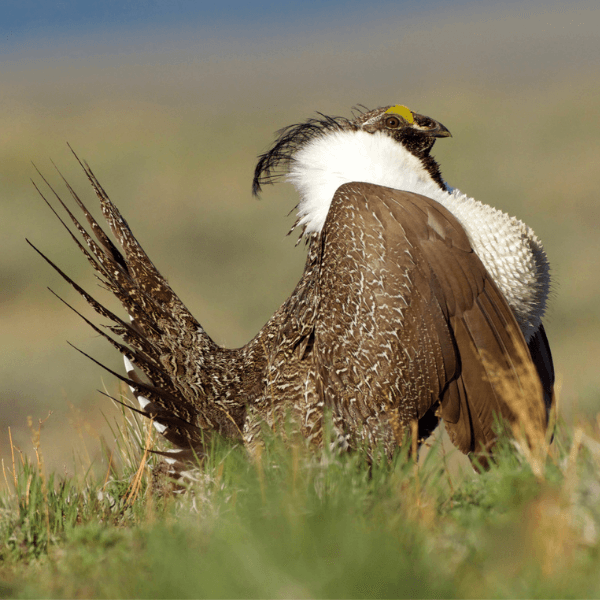

Each spring heralds a unique spectacle on the brushy western plains of North America. Year after year, male Greater Sage-Grouse congregate on ancestral display grounds known as leks. There, the males strut about, fanning spiky tail feathers and raising feathered white collars while inflating bright yellow throat sacs — all the while making a weird assortment of booming, swishing, and popping noises. Choosy female sage-grouse, the object of all this parading, look on with a critical eye.

Although male birds of other species, from the Greater Prairie-Chicken down to the Club-winged Manakin, also display on leks, the charismatic Greater Sage-Grouse is an “umbrella” species, meaning that efforts to conserve it also benefit a wide variety of other wildlife. It is one of the most prominent inhabitants of the sagebrush “sea,” which encompasses millions of acres of open lands across 16 U.S. states and small portions of a few Canadian provinces. And it’s uniquely adapted to this habitat, from its diet down to the downy fluff of sage-grouse chicks.

But the sagebrush “sea” is contested land, and the Greater Sage-Grouse’s foothold there has loosened. Over time, its habitat — among the most endangered in North America — has been lost to fossil fuel development, persistent grazing pressure, and introduced invasive grasses. Where 16 million Greater Sage-Grouse once strutted, now a severely reduced population, a bellwether for an entire, fragile ecosystem, hangs on.

Threats

Birds around the world are declining, and many of them, even iconic species like the Greater Sage-Grouse, are facing urgent, acute threats. Habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation, collisions, and pesticides hinder the species, and these threats are exacerbated by policy decisions. Despite clear evidence of a decreasing population, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service cannot list the Greater Sage-Grouse under the Endangered Species Act due to a moratorium imposed by the U.S. Congress in 2014. This exemption makes addressing issues contributing to the population’s decline even more difficult.

Habitat Loss

Oil and gas development, overgrazing, sagebrush removal, invasive plants such as cheatgrass, and poorly sited wind energy facilities have significantly degraded Greater Sage-Grouse habitat. According to the Sage Grouse Initiative, more than half the sagebrush ecosystem has been lost, with an additional 1.3 million acres disappearing each year, making it one of the country’s most endangered habitats.

Collisions

Greater Sage-Grouse sometimes collide with barbed wire fences and guy wires, and will avoid habitat near tall structures like wind turbines, communications towers, and powerlines. Fence collisions are especially common during the mating season, when sage-grouse are flying to and from leks and visibility is poor.

Pesticides & Toxins

Pesticides and herbicides may reduce the availability of forbs and insects, both important foods for nesting females and chicks during the breeding season. Greater Sage-Grouse may also be killed by exposure to insecticide sprays.

Conservation Strategies & Projects

ABC continues work with a variety of partners to get the Greater Sage-Grouse the conservation help it so urgently needs. Partners in Flight has included this species on its Red Watch List, and considers it a Tipping Point species — one that has lost more than 50 percent of its population within the past 50 years. Conserving the Greater Sage-Grouse also protects the dozens of species that share its sagebrush steppe habitat.

Restoring Habitat

ABC and other conservation groups have championed federal and state policies that would provide more comprehensive protections for Greater Sage-Grouse habitat. We continue to advocate for effective management plans that address the sage-grouse’s most urgent needs and prevent further fragmentation of its habitat.

The USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service has provided conservation resources through the Working Lands for Wildlife effort to target conservation of habitats vital to the Greater Sage-Grouse.

Rethinking Wind Turbines

If not sited properly, wind turbines, fences, towers, and oil installations can spell disaster for birds as they move about their habitats. ABC’s science-backed approach identifies the most critical areas for birds and provides guidance to industry that can help avoid collision risks.

Avoiding Pesticides & Toxins

ABC works with partners at the state and federal levels in the U.S. to call for the regulation or cancellation of the pesticides and toxins most harmful to birds. We develop innovative programs, like working directly with farmers to use neonicotinoid coating-free seeds, advance research into pesticides’ toll on birds, and encourage millions to pass on using harmful pesticides.

Bird Gallery

The Greater Sage-Grouse is the largest of North America’s grouse species. This impressive bird is heavy-bodied, with a short, thick neck and long tail. The sexes are dimorphic (they have distinctly different physical characteristics), and the male is larger than the female. Both have mottled gray-brown plumage with yellow lores (the area between the eye and the beak), a black belly, and white underwings, which are visible in flight. In addition, the male has a large white ruff that conceals two yellow patches of bare skin, known as gular sacs, on the lower throat and breast. During courtship displays, he inflates these patches into round, balloon-like pouches. The male also has a black throat, a fleshy yellow comb above the eyes, and long wispy feathers called filoplumes that arise from the back of his neck.

The female’s plumage is more uniformly mottled gray-brown, with less flashy white underwings and a shorter tail. This more cryptic plumage allows her to blend perfectly into her sagebrush habitat while nesting. She also has yellow eye combs, but they are less prominent than the male’s.

No subspecies of Greater Sage-Grouse are recognized, but there are distinct populations in Washington state and on the border between California and Nevada. There is also the Gunnison Sage-Grouse, a closely related species, which occurs mostly in Colorado. Gunnison Sage-Grouse are significantly smaller in size, and males have more noticeably barred tails.

Bird Sounds

The Greater Sage-Grouse utters a chicken-like cackling call when flushed from cover. Displaying males make a weird assortment of booming, swishing, and popping noises, produced by rattling their stiff tail and wing feathers and inflating and deflating their throat sacs.

Sue Riffe, XC368674. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/368674.

Andrew Spencer, XC77183. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/77183.

Habitat

Greater Sage-Grouse are only found on the sagebrush steppe and are closely associated with sagebrush ecosystems in all seasons, utilizing different sagebrush habitats throughout the year.

- Revisits sites year after year for lekking, using locations with less shrub cover but proximity to nesting habitat, including sparsely vegetated sites such as dry lakebeds and broad ridgetops, and human-altered habitats such as cultivated fields, airstrips, gravel pits, and roads.

- Nests under the cover of dense big sagebrush plants and in other grassy areas. Native bunchgrasses in the sage understory are of particular importance for nesting.

- Hens and juveniles forage in wet meadows and irrigated pastures.

Range & Region

Specific Area

Current range includes Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, Alberta, and Saskatchewan

Range Detail

The Greater Sage-Grouse is an icon of the sagebrush “sea,” the sprawling open lands that cover millions of acres in 16 U.S. states and small parts of Canada. This bird relies on the sagebrush habitat for leks, nesting sites, feeding sites, rearing sites, protection, and nonbreeding grounds. Sage-grouse can be found in or near these habitats year-round. In 2025, it was announced that the Greater Sage-Grouse had been extirpated from North Dakota.

The sagebrush sea is more complex than it first appears, with many varieties of native sagebrush, bunchgrasses, and wildflowers. These plains are home to hundreds of bird species besides the grouse, including the Sagebrush Sparrow and Sage Thrasher, plus scores of other animals ranging from the unique pronghorn antelope to the Great Basin spadefoot toad. It is also an important migratory corridor for birds and provides winter habitat for mule deer and elk.

Did you know?

Although the Greater Sage-Grouse is a permanent, year-round resident throughout its range, it may make short seasonal movements sparked by food availability and weather. It will move to lower elevations with less snow during the winter, from lekking areas to brood-rearing habitat during the breeding season, and to different types of sagebrush habitats throughout the year. Like its cousins on the prairie, the Greater Sage-Grouse is capable of sustained flights of as much as 50 miles or more.

Life History

The Greater Sage-Grouse and the sagebrush ecosystem it inhabits are inseparable: The grouse can’t live without the sagebrush, and the ecosystem’s health hinges on the survival of the grouse. The rhythm of the grouse’s life is tied to the resources the sagebrush steppe provides — from the stage it sets for lekking males and the cover it offers brooding hens on nests to the diet of dispersing juveniles. Two particular sagebrush species, big sage and silver sage, are perhaps the most important for the Greater Sage-Grouse.

Diet

The Greater Sage-Grouse needs large, connected expanses of healthy sagebrush habitat to thrive. Since it lacks a muscular gizzard like other birds have, it cannot grind and digest hard seeds, and must feed on softer plant material. Sagebrush buds, leaves, and bunchgrasses constitute more than 70 percent of its diet year-round, supplemented by insects, fruits, and small amounts of grit. The sage-grouse forages on the ground in open habitats, seeking sheltered feeding spots in harsh weather.

Courtship

Male Greater Sage-Grouse are well-known for their display “dances” on traditional gathering grounds known as leks. Traditional lekking grounds may be used for many years. Although many male sage-grouse gather to display at a lek, only a few are chosen by the majority of visiting females for mating. Males strut, inflating their yellow gular sacs and fanning their spiky tails to attract the attention of females nearby. After mating, the females disperse to areas around the lek to nest.

Nesting

A hen will build her nest under a sagebrush or other large shrub in a well-hidden, grass-lined depression on the ground, often under a canopy of both sage and native bunch grass. Like other lekking species such as the Lesser Prairie-Chicken and Buff-breasted Sandpiper, the Greater Sage-Grouse male plays no role in raising the young.

Eggs & Young

The Greater Sage-Grouse hen lays a clutch of six to 10 eggs, which she incubates herself. The downy chicks hatch after two to three weeks and immediately walk out of the nest to follow their mother. In their first week of life, chicks eat many protein-rich insects to accommodate rapid growth and two separate molting processes. Since they can’t fly for a few weeks, they must find everything they need to live close to the nest site. Young sage-grouse switch to a plant-based diet as they mature.

Greater Sage-Grouse hens and their young sometimes gather with other females in food-rich areas. Post-breeding, other individual grouse may join these groups, sometimes forming winter flocks that number in the hundreds.