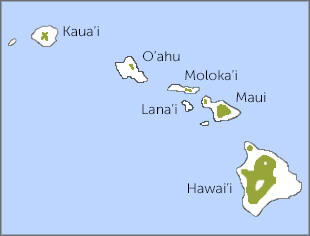

ʻIʻiwi range map, Birds of North America, https://birdsna.org maintained by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

The eye-catching ʻIʻiwi (pronounced "ee-EE-vee") was once one of the Hawaiian Islands' most common forest birds. In Hawaiian mythology, the demi-god Maui particularly loved the native forest birds and painted them in bright reds and golds. Maui made the ʻIʻiwi especially colorful, with a unique call that resonated throughout the forest.

Hawaiians treasure the ʻIʻiwi, but this signature island bird is becoming scarce. Like many other native species, such as the Maui Parrotbill and the Palila, it has disappeared from most of its former range. Tiny, six-legged creatures are partly to blame.

Hanging On in the Heights

As is the case with other Hawaiian forest birds — many of which have gone extinct — the ʻIʻiwi has declined in large part due to widespread habitat loss. But the introduction of alien animals, plants, and even insects that came along with European settlers in the 19th century have also taken an enormous toll. One of these, the mosquito, has posed particular problems, since the ʻIʻiwi and most other Hawaiian honeycreepers have no immunity to avian malaria and avian pox transmitted by these nonnative insects.

Research has shown that 90 percent of ʻIʻiwi bitten by a single malaria-infected mosquito die from the disease. Climate change is compounding this threat, as warming temperatures allow mosquitoes to move into higher elevators, including into forest birds' remaining mountain strongholds.

And there's yet another attack underway in the ʻIʻiwi's habitat. Brought on by two introduced plant pathogens, a syndrome called Rapid ʻŌhiʻa Death (ROD) is causing large-scale dieback of ʻōhiʻa trees, which are important food sources for ʻIʻiwi. While some ʻōhiʻa seem to be resistant, ROD has spread to nearly 100,000 acres on the island of Hawaiʻi. There is no known cure.

ʻIʻiwi were once found on all of the main Hawaiian islands. Today, most of the ʻIʻiwi population hangs on in higher-altitude forests (4,300 to 6,200 feet) on Maui, Hawaiʻi, and Kauaʻi, with a remnant population on Oʻahu and Molokaʻi. They are found nowhere else in the world.

Colors of Ceremonial Splendor

ʻIʻiwi are important to their islands' culture. Early Hawaiians considered their native birds' red colors to be sacred and used ʻIʻiwi and other honeycreeper feathers to create elaborate cloaks, helmets, and leis. This garb became a mark of societal rank and was worn only during special ceremonies, or into battle.

Bird catchers, called kia manu, trapped large numbers of then-common native forest birds, as thousands of feathers were needed to make a single cloak. Most bird catchers took only a few feathers from each bird, releasing them back into the wild to preserve the precious resource. Today, Hawaiian artists carry on this tradition by using dyed feathers from common domestic birds such as geese and pheasants.

Specialized Nectar-Sipper

The ʻIʻiwi's long, downward-curving bill is specialized for probing tubular native lobelia and mint flowers to reach their nectar. As these plants have become less common due to habitat loss, ʻIʻiwi have turned to the flowers of the native ʻōhiʻa tree as well. They also eat spiders as well as moths and other insects.

Like another red Hawaiian honeycreeper, the ʻApapane, the ʻIʻiwi is an altitudinal migrant, following blooms of nectar-producing plants up and down mountain slopes throughout the year. This behavior can be risky for both species as they move to lower elevations and come into contact with disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Subfamily of Finch-like Birds

DNA studies indicate that the ʻApapane is one of the ʻIʻiwi's closest relatives, along with another endemic Hawaiian honeycreeper, the ʻĀkohekohe. All three are part of the Carduelinae subfamily, a varied group of finch-like birds that includes the American Goldfinch and Pine Siskin.

The song of the ʻIʻiwi is a unique collection of whistles, sometimes compared to balloons rubbing together, or a squeaky hinge. Listen here:

(Audio of ‘Iʻiwi by Daniel Lane, XC27366. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/27366)

The peak breeding season for ʻIʻiwi is from February to June. Both the male and female build the nest, a cup fashioned from twigs, bits of ferns, and lichens, high in the crown of a native tree. The female lays two to four eggs, which she then incubates for 14 days. In 21 to 24 days after hatching, the chicks fledge.

Juvenile ʻIʻiwi are mottled with black and yellow-brown but soon molt into bright scarlet-and-black adult plumage.

Juvenile ʻIʻiwi, Haleakalā National Park, Maui. Photo by Alan Schmierer

Battling on Several Fronts

Introduced mammals have taken a terrible toll on Hawaiʻi's native forest birds. The birds fall victim to nonnative predators, including cats, rats, and mongooses, and habitats are lost due to uncontrolled grazing by feral pigs, sheep, deer, and goats.

Our Hawaiʻi program is committed to protecting remaining habitats and native bird populations, working in partnership with many other groups. To help stop the spread of introduced diseases such as avian malaria, we're working on advances in biotechnology aimed at modifying, suppressing, or even eliminating mosquitoes.

ABC is also helping fund rat control efforts on Kauaʻi, in cooperation with the Kauaʻi Forest Bird Recovery Project and with funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and other organizations.

Saving Hawaiian Seabirds

Another group of Hawaiian birds is also a priority for ABC: seabirds. We've supported construction of predator-proof fencing at Kīlauea Point National Wildlife Refuge on Kauaʻi, as well as translocations of Endangered Hawaiian Petrel (ʻUaʻu) and Critically Endangered Newell's Shearwater (ʻAʻo). We hope that these efforts will give rise to new colonies of these imperiled seabirds.

At Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park, we supported construction of a cat-proof fence to protect another important Hawaiian Petrel breeding site. Learn more about our work to protect seabirds.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!