Getting Clear on Birds and Glass

Glass collisions kill vast numbers of birds in the United States each year. Yet most Americans know little about this danger, and even fewer are aware of the solutions available to help prevent these deaths — fixes that in many cases are easy and inexpensive.

To shed light on this pervasive threat, ABC's collisions experts, Christine Sheppard, Ph.D., and Bryan Lenz, Ph.D., put together a list of responses to the 15 questions they are most frequently asked. Take a look. Chances are, we've got an answer for you below.

Birds killed by glass collisions in Toronto. Photo by FLAP/Kenneth Hrdy

1) How many birds are killed by glass collisions in the U.S. each year?

Because glass is used so widely, giving a definitive answer is difficult, but Smithsonian researchers attempted to do so in 2014.

They estimated that homes and other buildings one to three stories tall accounted for 44 percent of all bird fatalities, about 253 million bird deaths annually. Larger, low-rise buildings four to 11 stories high caused 339 million deaths. And high-rise buildings, 11 floors and higher, kill 508,000 total birds annually. Individual skyscrapers can be quite deadly for birds, but they kill fewer birds overall due to their limited numbers.

By combining these numbers, the Smithsonian reported that collisions likely kill between 365 million and 1 billion birds annually in the United States, with a median estimate of 599 million1.

We believe that the true number is closer to a billion, or higher, for several reasons. For one, data used in the study is now more than ten years old, and there has been a steady increase in glass use since that time, increasing the likelihood of fatal collisions. In addition, we've learned that bird carcass reports tend to underestimate deaths (see questions 4 and 5), meaning that more dead birds go uncounted than we realized.

This means that the only anthropogenic (human-caused) threat that kills more birds in the United States each year is domestic cats2.

2) Why do birds collide with glass?

Transparent glass is invisible to both humans and birds, but humans can use door frames and other visual clues to anticipate the presence of glass and avoid collisions — most of the time. Birds, of course, don't share this ability. They perceive reflected images as literal objects, which explains why glass reflections, especially ones that present images of food, shelter, or an escape route, can trigger collisions. Learn more by visiting our “Why Birds Hit Glass” page.

Reflections can draw birds toward windows. Photo by Christine Sheppard

3) Are birds okay when they hit windows and fly away?

After colliding with glass, some birds may be only temporarily stunned and without lasting injury — but often they are not so lucky.

In many of these cases, birds suffer internal hemorrhages, concussions, or damage to their bills, wings, eyes, or skulls3. While they may be able to fly temporarily, birds with even moderate injuries are much more vulnerable to predators and other environmental dangers.

In many instances, however, birds are killed immediately and never fly away.

4) Why don't I see birds that have been killed by collisions more often?

Collisions often go unnoticed at both homes and commercial buildings for several reasons. First, many of the birds that hit windows do not die immediately and fly off without leaving a trace.

One study found that, out of 29 window collisions, only two birds died immediately and left a carcass that at the foot of the window4. However, birds can sustain severe injuries such as fractured bones and beaks, concussions, and internal bleeding3, so even birds that initially fly away likely die elsewhere.

Second, for those birds that do die and end up at the base of the building, animal scavengers often quickly remove carcasses. Cats, raccoons, birds of prey, and even squirrels, can learn to wait at windows where collisions occur for an easy meal.

Birds may also fall on inaccessible rooftops, fall through grates, end up in landscaping, or land in dense vegetation that makes them difficult to see.

5) Do collision monitoring programs find all collision victims?

Even for intensive collision monitoring programs the total number of dead birds found are always a large underestimate of the number of birds that actually collided with the glass. This is the case for reasons similar to the answer above.

Many of the birds that hit windows do not die immediately and fly off without leaving a trace. One study found that, out of 29 window collisions, only two birds died immediately and left a carcass that at the foot of the window4. However, birds can sustain severe injuries3, so even birds that initially fly away might die elsewhere.

Second, for those birds that do die and end up on the ground, animal scavengers – and people, frequently facilities teams – often remove carcasses before monitors can find them. Collision monitors even report animals, such as gulls and squirrels, learning to wait at windows where collisions occur for an easy meal. This problem is so serious that academic monitoring efforts conduct “carcass persistence studies” to estimate the number of dead birds removed before monitors walk their routes and find them5,6.

The rate at which dead and injured birds disappear can vary a lot from site to site7; researchers have found that in some places carcasses are removed within hours8 while at others it takes days5,6,7. At some locations in NYC, for example, only 25% of carcasses placed on collision monitoring routes remained when collisions monitors walked their routes later the same morning8.

Finally, for those birds that are left, monitors do not always detect all of them9. Birds may fall on inaccessible rooftops, fall through grates, end up in landscaping, land in dense vegetation that makes them difficult to see, be swept away in the gutter, or just overlooked because they blend in with the ground.

In one study where researchers accounted for both scavenging and imperfect detection, they estimated that only about 20% of birds killed were actually found by people who were searching for them9. So, it is safe to say that any number of birds picked up in a monitoring effort especially if it is not a rigorous monitoring effort, is going to be a small fraction of the birds that actually died and an even smaller fraction of the total number of birds that hit the windows.

6) How do I stop birds from hitting my windows?

There are many ways to making windows bird-friendly. One of the best is to use external insect screens. These screens virtually eliminate reflections, and if birds do hit them, the impact is cushioned, reducing the likelihood of injury. An added benefit is that these screens are easy to install on existing or new home windows.

If screens aren't an option, you can use a range of materials — tape, decals, strings, cords, paint, netting, and shutters are options — to create window patterns that birds will interpret as solid objects, needing to be avoided. Check out our great home-friendly solutions guide here.

It's important to make sure that birds see no viable way to fly between the markers or objects you're using, so make sure to eliminate all spaces larger than two inches.

Remember, whichever material you use needs to be visible to birds from at least ten feet away so that they have time to see the material and change course.

Bird-friendly window products are effective, inexpensive, and easy to install. Photo by ABC

7) Can I apply something to the inside of my windows to stop bird collisions?

The best place to apply solutions is on the outside of the window, where they are easily visible.

However, using external solutions isn't always an option. Some windows — like those on tall buildings — can be difficult to access from the outside.

In these cases, we recommend testing a variety of solutions. This is because different kinds of glass have varying reflective levels and, unfortunately, there is no universal solution.

To conduct a test, apply a sticky note, tape, or sample of your proposed solution to the inside of the window and then look at it from the outside every hour or two, starting in the early morning.

If you can see your test material most of the time, birds will too, and an inside solution may work for you.

In many cases, however, internal solutions do not work, and reflections will hide your solution during part or all of the day, thereby reducing or eliminating its effectiveness.

But this shouldn't deter you from acting. is better than doing nothing. Adding something to your windows is better than doing nothing.

The intensity of window reflections varies during the course of the day, affecting the danger to birds. Photo by Christine Sheppard

8) Will bird-friendly window products obscure the view from my window?

No, you don't need to impair your view to save birds.

There are effective solutions that cover as little as 1% of the window area, allowing sunlight in and a view out. In our experience, people quickly adjust to bird-friendly design solutions, often forgetting that they are even there. We have also found that when family, friends, or customers notice the pattern and learn its purpose, they appreciate the effort to protect birds.

If you're looking to retrofit existing windows, there is a wide range of solutions from which to select, depending upon personal preferences.

If you are designing a new building or replacing windows, consider the professional solutions favored by architects. Many of these elegant products have enjoyed long-standing popularity among architects for their aesthetic appeal alone. For more on designing a new building or replacing windows, visit the "Resources for Architects, Planners, and Developers" page. Looking for inspiration? Check out our bird-friendly building gallery.

Bird-friendly window products have little impact on views. Photo by Arenal Observatory Lodge

9) Does light cause birds to hit buildings?

Light can increase collision numbers in several ways. Recent studies confirm that urban glow attracts birds into the human-built environment10,11, where they run a higher risk of collisions.

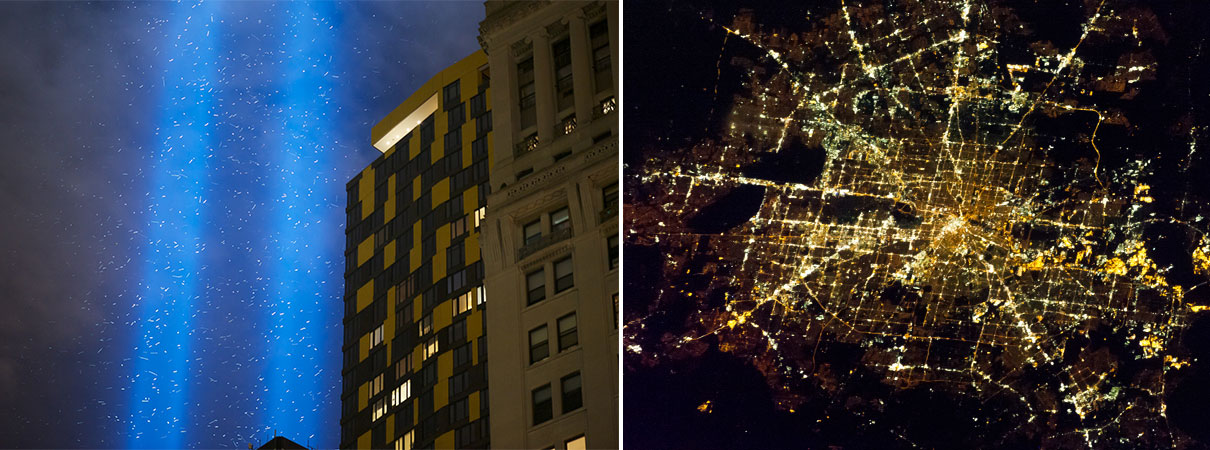

Migratory birds traveling at night are also attracted by intense lights contrasted against the night sky. The “beacon effect,” as this occurrence is commonly known, can be caused by lighthouses, offshore oil platforms, or powerful light displays, like the twin beams at the 9/11 Tribute in Lights memorial in New York City. These lights can thoroughly disrupt birds' ability to navigate, pulling them off course and effectively trapping them around the light12 or disorienting them. At the 9/11 memorial, volunteers monitor the birds and the lights are turned off when needed to allow safe passage.

Brightly lit building facades can also affect birds. In some cases, these facades and brightly lit windows can cause collisions at night13,14. These birds are seen fluttering at lit windows or exhausted on the ground14 where they are vulnerable to predators.

Despite the dangers posed by nighttime lights, it's important to note that most collisions take place during the day. These collisions are due to habitat reflected in or seen through glass, and they are often direct and deadly.

While turning off lights is a great way to help birds and other wildlife, the best way to prevent collisions, especially at homes, is to use one of the many options available to treat your windows.

The World Trade Center memorial light has a "beacon effect" upon birds. Photo by jnap/Flick. Houston, as viewed at night from space, demonstrates the growing impact of light pollution. Photo by NASA

10) I put a decal up, but birds still hit my windows. What can I do?

A single decal may be enough to warn an alert human to expect a glass door, but for a bird it's simply an obstacle to fly around.

To successfully deter birds, decals and other collision deterrents must be applied with proper spacing to create the illusion of a cluttered environment through which it would be difficult or impossible to fly. You can learn more here. Remember to make sure that whichever pattern you use on your windows should not have any spaces more than two inches wide.

11) What can I do about a building that causes collisions in my town?

The first thing to do is document the problem. Take photos of the dead birds you find and keep a list of numbers and dates.

If there is a facilities or maintenance department, ask what they have noticed; they are usually responsible for cleaning up birds that have died after hitting glass and may be great allies who help you collect data or convince building managers of the danger to birds.

After documenting the problem, review the window solutions on ABC's site, contact the building owner or manager to tell her or him about the problem, and provide advice or resources (such as this blog) on how to address it.

Keep in mind that you are making a request and looking for a partner to save birds, so be sure to keep these interactions positive and non-confrontational. Avoid vilifying the responsible party for a collision problem that they likely had no idea existed.

You can also talk to people who live, work, or shop in the building in question to see if anyone else shares your concerns. If so, ask them if they would like to be involved. By working with others, you build a collective voice that can draw more attention to the problem.

Remember, there are many ways to get involved. These include helping with monitoring, writing letters to building owners, attending meetings with building management, and organizing community action.

For more tips see our “How to Advocate for Retrofits” page.

Window imprint from bird collision. Photos by David Fancher

12) What can I do to keep buildings that harm birds from being constructed where I live?

Buildings designed without bird-friendly design principles have the potential to be deadly for birds.

A variety of factors determine the level of the threat they pose, including the amount of glass used, placement and reflectivity of the glass, the height and extent of vegetation around the building, and the presence of water, among other things.

Given incremental cost of constructing a bird-friendly building, we believe that all new buildings — not just glass-covered skyscrapers — should incorporate bird-friendly features. It is less expensive to incorporate these features from the beginning of the planning process, compared to retrofitting a building later.

There are several ways to help make this happen. The first is to develop and pass a local ordinance requiring the adoption of bird-friendly building standards in your community. To download an easy-to-use ordinance template, click here. You can also take a look at our list of existing ordinances mandating bird-friendly design or creating voluntary standards.

Keep in mind that ordinances tend to apply to large buildings and exempt low rises and homes, so it is important to make sure that the ordinance applies to as many buildings as possible.

Although passing an ordinance is a great accomplishment, it's not the only thing you can do.

Consider approaching the developers of new and proposed building projects with your concerns. Since this can be a time-consuming process, we suggest focusing on projects with a high likelihood of success (e.g., nature centers, museums) or organizations that influence multiple buildings (e.g., local government, universities, health care organizations, and architecture firms) to help them adopt bird-safe building policies.

While it's critical to make sure that new buildings incorporate bird-friendly designs, don't forget that existing buildings already account for hundreds of millions of bird deaths annually. Consequently, the need to retrofit homes and other buildings will remain an important way to reduce bird collisions for the foreseeable future.

To learn more visit our “Creating Bird-Friendly Legislation” page.

Bird-friendly building design can improve a building's appearance while reducing bird deaths. Photo by Almere

13) Are all LEED-rated buildings bird-friendly?

Not necessarily. When architects, developers, and other stakeholders intend to create a LEED-rated building, they review available credit options and select the amount of credits needed for the rating they want.

Bird-friendly credits, however, weren't available until 2011, when the LEED program adopted a new, bird-focused building design credit known as “Pilot credit SSpc55: Bird Collision Deterrence.” LEED added a permanent “Bird Collision Deterrence” credit to the Innovation Catalogue in 2022.

Like all credits in the LEED system, the use of this bird-friendly credit is not mandatory. So, while many builders have opted to use this credit, not all LEED-rated buildings are bird-friendly.

Regardless of LEED rating, we strongly encourage architects and builders to incorporate bird-friendly buildings guidelines into their designs. To find out more about testing and LEED ratings, visit our LEED Innovation Credit page.

14) When do most bird collisions with glass take place?

Collisions don't happen at an even pace over the course of a year, or even throughout the day.

Most collisions happen during daylight hours or immediately before dawn, with some occurring at night. Mornings, in particular, tend to be the worst time of day for collisions15,16,17, 18. During migration, this is because migratory birds that have flown all night stop to look for a place to land and refuel. Those that land in and near cities find themselves in a maze of deadly glass. In addition, resident birds are generally most active in the morning, as they wake up hungry and immediately search for food.

During the course of a year, migration periods often bring the largest upticks in collisions, when huge numbers of birds stop to rest, often in unfamiliar areas where glass is common10,19,20. Many collisions programs are focused collisions during migration in cities where they tend to occur in large numbers. Migrant mortality in fall tends to be worse than spring due to the larger number of birds in flight. This is because fall migration includes both adult birds and juveniles that were born over the summer. Spring migration includes only adults returning to breed.

But migration is not the only dangerous season. We also see collision increases in late spring18, as nesting birds fledge their young, and in winter21,22, when resident birds leave their territories and cover larger areas in search of food. In the winter, bird feeders near windows can be a cause of mortality from collisions23.

Cerulean Warblers (above) and other migratory birds face increased collision dangers in the fall and spring. Photo by Jacob Spendelow

15) What does ABC do to protect birds from glass collisions?

American Bird Conservancy strives to reduce bird-and-glass collisions by making the human-built environment as safe as possible for birds. To maximize our impact, we focus on the following areas:

Product testing: We operate a flight tunnel to better understand how birds interact with various commercially available window treatments (watch our video to learn more). These evaluations help us create bird-friendly building guidelines for architects and recommend effective solutions for people living in homes and other buildings. As experts in the field, we also evaluate and document scientific literature related to bird collisions.

Legislation, codes, and LEED: We help promote science-based, bird-friendly legislation based on the results of tunnel tests conducted by ourselves and other researchers. For example, we worked with members of Congress to draft the national Bird-Safe Buildings Act, which would require public buildings to incorporate bird-friendly building design and materials. We have also helped to establish building guidelines like the LEED Bird Collision Deterrence Innovation Credit and pass local ordinances. Check out the Bird-friendly Legislation tab on our Legislation page for more details.

Educating architects and engineers: ABC offers a bird-friendly building design course that architects can take for continuing education credit from the American Institute of Architects and the Green Building Council.

Guidance on retrofits and monitoring: ABC helps businesses, universities, and individuals create effective monitoring programs and select the right solutions to reduce collisions.

Public education and outreach: A large part of ABC's collisions mission is raising public awareness about this issue. We connect people with solutions and provide detailed information to homeowners, architects, engineers, and lawmakers.

New initiatives: We are always working to improve bird-friendly window products while encouraging public action to reduce bird mortality rates. To keep up with our collisions program, you can sign up to receive email updates, or follow us on Facebook or X (formerly Twitter).

Dr. Christine Sheppard is ABC's Bird Collisions Campaign Director. She earned her Ph.D. at Cornell University and worked as head of the Bronx Zoo's Ornithology Department before joining ABC. Since then, she has authored both editions of the ABC publication Bird-friendly Building Design. She created AIA/LEED continuing education classes on Bird-friendly Design, helped design San Francisco's Standards for Bird-safe Buildings, and has been involved in writing code and legislation in many different locations. Sheppard helped develop the USGBC LEED Pilot Credit 55: Reducing Bird Mortality. She was named an Engineering News-Record "Top 25 Newsmaker for 2014" because of her work on glass testing, and has worked with most major glass manufacturers on design and evaluation of bird-friendly materials.

Dr. Christine Sheppard is ABC's Bird Collisions Campaign Director. She earned her Ph.D. at Cornell University and worked as head of the Bronx Zoo's Ornithology Department before joining ABC. Since then, she has authored both editions of the ABC publication Bird-friendly Building Design. She created AIA/LEED continuing education classes on Bird-friendly Design, helped design San Francisco's Standards for Bird-safe Buildings, and has been involved in writing code and legislation in many different locations. Sheppard helped develop the USGBC LEED Pilot Credit 55: Reducing Bird Mortality. She was named an Engineering News-Record "Top 25 Newsmaker for 2014" because of her work on glass testing, and has worked with most major glass manufacturers on design and evaluation of bird-friendly materials.

Dr. Bryan Lenz is ABC's Bird Collisions Campaign Manager. He earned his Ph.D. at Tulane University and worked as the Director of the Community Conservation program at Bird City Wisconsin, and as the Chief Scientist at the Western Great Lakes Bird & Bat Observatory. At ABC, Bryan works to reduce the collision threat that the built environment, especially glass, poses to birds. His work incorporates research, design, legislation, building codes, education, outreach, and marketing.

Dr. Bryan Lenz is ABC's Bird Collisions Campaign Manager. He earned his Ph.D. at Tulane University and worked as the Director of the Community Conservation program at Bird City Wisconsin, and as the Chief Scientist at the Western Great Lakes Bird & Bat Observatory. At ABC, Bryan works to reduce the collision threat that the built environment, especially glass, poses to birds. His work incorporates research, design, legislation, building codes, education, outreach, and marketing.

- Loss, Scott R., Tom Will, Sara S. Loss and Peter P. Marra. 2014. Bird–building collisions in the United States: Estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability. Condor 116:8-23. https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-13-090.1

- Loss S.R., Will T., and Marra P.P. 2013. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nature communications 4(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2380

- Klem, D., Jr. 1990. Bird injuries, cause of death, and recuperation from collisions with windows. Journal of Field Ornithology 61(1):115- 119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4513511

- Samuels B, Fenton B, Fernández-Juricic E, & MacDougall-Shackleton SA. 2022. Opening the black box of bird-window collisions: passive video recordings in a residential backyard. PeerJ 10:e14604 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14604

- Kummer, J. A., C. J. Nordell, T. M. Berry, C. V. Collins, C. R. L. Tse, and E. Bayne. 2016. Use of bird carcass removals by urban scavengers to adjust bird-window collision estimates. Avian Conservation and Ecology 11(2):12. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ACE-00927-110212

- Riding, Corey S. and Scott R. Loss. 2018. Factors influencing experimental estimation of scavenger removal and observer detection in bird–window collision surveys. Ecological Applications 28(8): 2119-2129. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1800

- Hager, Stephen B., Bradley J. Cosentino and Kelly J. McKay. 2012. Scavenging effects persistence of avian carcasses resulting from window collisions in an urban landscape. J. Field Ornithol. 83(2) 203-211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1557-9263.2012.00370.x

- Parkins, Kaitlyn L, Susan B. Elbin and Elle Barnes, 2015. Light, glass, and bird–building collisions in an urban park. Northeastern Naturalist 22(1): 84- 94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1656/045.022.0113

- Bracey, Matthew A. Etterson, Gerald J. Niemi, and Richard F. Green. 2016. Variation in bird-window collision mortality and scavenging rates within an urban landscape. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 128(2):355- 367. https://doi.org/10.1676/wils-128-02-355-367.1

- La Sorte FA, Fink D, Buler JJ, Farnsworth A, and Cabrera-Cruz SA. 2017. Seasonal associations with urban light pollution for nocturnally migrating bird populations. Glob Change Biol. 23:4609–4619. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13792

- McLaren, J. D., Buler, J. J., Schreckengost, T., Smolinsky, J. A., Boone, M., Emiel van Loon, E., Dawson, D. K. and Walters, E. L. 2018. Artificial light at night confounds broad-scale habitat use by migrating birds. Ecol Lett. 21(3):356-364. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12902

- Van Doren, Benjamin M., Kyle G. Horton, Adriaan M. Dokter, Holger Klinck, Susan B. Elbin and Andrew Farnsworth. 2017. High-intensity urban light installation dramatically alters nocturnal bird migration. Proc Nat Acad Sci: 114 (42) 11175–11180. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.170857411

- Van Doren, Benjamin M., David E. Willard, Mary Hennen, Kyle G. Horton, Erica F. Stuber, Daniel Sheldon, Ashwin H. Sivakumar, Julia Wang, Andrew Farnsworth, and Benjamin M. Winger. 2021. Drivers of fatal bird collisions in an urban center. PNAS 118(24):e2101666118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2101666118

- Korner, P., von Maravic, I. and Haupt, H. Birds and the ‘Post Tower' in Bonn: a case study of light pollution. J Ornithol 163, 827–841 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-022-01985-2

- Gelb, Y. and N. Delacretaz. 2006. Avian window strike mortality at an urban office building. Kingbird 56(3):190-198. https://nybirds.org/KBsearch/y2006v56n3/y2006v56n3p190-198gelb.pdf

- Hager SB, Craig ME. 2014. Bird-window collisions in the summer breeding season. PeerJ2:e460. https://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.460

- Kahle LQ, Flannery ME, and Dumbacher JP. 2016. Bird-window collisions at a west-coast urban park museum: Analyses of bird biology and window attributes from Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. PLoS ONE 11(1): e0144600. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144600

- Riding, C.S., O'Connell, T.J. & Loss, S.R., 2021. Multi-scale temporal variation in bird-window collisions in the central United States. Scientific Reports 11(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89875-0

- Borden, W.C., O.M. Lockhart, A.W. Jones and M.S. Lyonn. 2010. Seasonal, taxonomic and local habitat components of bird-window collisions on an urban campus in Cleveland, OH. Ohio J Sci 110(3):44-52. https://kb.osu.edu/handle/1811/52787

- Scott KM, Danko A, Plant P, Dakin R. 2023. What causes bird‐building collision risk? Seasonal dynamics and weather drivers. Ecology and Evolution 13(4):e9974. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9974

- Brown B.B., L. Hunter, and S. Santos. 2020. Bird-window collisions: different fall and winter risk and protective factors. PeerJ 8:e9401 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9401

- De Groot, Krista L., Porter Alison N., Norris Andrea R., Huang Andrew C., Joy Ruth. 2021.Year-round monitoring at a Pacific coastal campus reveals similar winter and spring collision mortality and high vulnerability of the Varied Thrush, Ornithological Applications 123(3):duab027. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144600

- Dunn, E. H. 1993. Bird mortality from striking residential windows in winter. Journal of Field Ornithology 64(3):302-309. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4513821