Return of the Millerbird

Decades of research, planning, and action by ABC and partners led to a big win for this little-known Hawaiian songbird.

September 2011 was a momentous time in the history of the Millerbird, a songbird at risk of extinction and at that time found only in one place in the world: Nihoa Island in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. On September 10, we and the rest of our conservation team celebrated as we released 24 Millerbirds on their new home, Laysan Island (Kauō). This was an essential first step toward creating a second “insurance” population for the Endangered species. But three days earlier, on September 7, the journey was off to a slippery start, and our biggest challenge had yet to be overcome.

Precious Cargo

It was one of the most dramatic moments of the expedition: Team member Daniel Tsukayama balanced on slick rocks at the landing site on Nihoa, battling the surf surge. Even worse, he was holding a transport cage containing four of the 24 precious Millerbirds above the swells. As he tried to pass the cage to teammates waiting on the inflatable Zodiac raft, bobbing a few feet away, a swell pushed turbulent, foamy seas up and over Daniel's waist, threatening to drag him off the rocks. It was seriously hairy!

Thankfully all 24 birds were transferred to our ship, the Searcher, without incident. But the 12 members of the team were wondering: What would the 650-mile sea voyage to Laysan bring? If it was rough, would the birds feed? Would they survive? It was one of the greatest unknowns of the whole venture. So, it was like something out of a dream when our passage to Laysan was over the flattest, most breathless seas imaginable — mirror-calm water punctuated only by the occasional flying fish skittering away from the ship, Bottlenose Dolphins surfing our bow wave, or a Black-winged Petrel vaulting by. Below deck, the Millerbirds did well; some even gained weight! It looked like we might actually pull this off. (Spoiler alert: We did!)

More than a decade later, in December 2023, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) downlisted the Millerbird from Critically Endangered to Endangered due to the ongoing success of the species on Laysan Island. That success was never guaranteed, though. In fact, given the long history of extinctions in Hawai‘i, the odds were not in our favor.

Bird Extinction Capital of the World

The Hawaiian Islands are one of the world's most isolated archipelagos, an island chain 1,500 miles long strewn across the northern Pacific approximately 2,000 miles from North America and 4,000 miles from Asia. Over millions of years, Hawai‘i was colonized by plants and animals that evolved into a diverse array of species found nowhere else in the world. Unfortunately, the remoteness of the Hawaiian Islands also led to the vulnerability of its bird populations. Humans brought non-native mammals as the islands were colonized, first by Polynesians starting in the 4th century CE and later by Europeans starting in the late 1700s. With people also came many species of non-native plants, insects, birds, and microorganisms. Having evolved in isolation, with no land mammals and without many other common continental species, the native birds were not adapted to living with mammalian predators, such as rats, cats, and mongooses. The plants were not resistant to non-native sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs, or introduced plant pathogens. Many native bird species, especially the Hawaiian honeycreepers, lacked resistance to avian malaria and avian pox virus. Hawai‘i is now known as the “Bird Extinction Capital of the World.” At least 106 species have gone extinct, and most of the remaining 35 species survive in greatly reduced fragments of their former ranges; most are listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Like most island systems across the world, they suffered catastrophic losses when continental or more cosmopolitan species invaded. The even more remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands were not spared, and their delicate ecosystems were even more vulnerable. Until the late 1800s, tiny Laysan, approximately 1,000 acres and over 900 miles from Honolulu, was virtually unknown, but by the 1920s it had been completely degraded. Home to vast numbers of seabirds, Laysan was exploited for its guano during 1896-1909, when Maximilian Schlemmer, a German immigrant, leased it from the Hawaiian territorial government.

Schlemmer introduced rabbits and guinea pigs in hopes of establishing a canned meat business, and he allowed feather hunters to illegally harvest seabirds, removing tons of feathers. The rabbits defoliated the island. Laysan was home to a subspecies of the Millerbird, which was first reported in 1891, but only two decades later, in 1911, researchers visiting to assess damage to the seabird populations suggested that the Laysan Millerbird might need to be moved to other islands because Laysan's vegetation had been so devastated by the rabbits.

A 1912-13 expedition to eradicate the rabbits on Laysan failed, and it was not until 1923 that the last rabbits were finally eliminated. However, by then, the Laysan Millerbird, Laysan Honeycreeper, and Laysan Rail were all extinct. The Laysan Finch and Laysan Teal survived. Both are now listed as Endangered under the ESA, and the teal has been the subject of intensive conservation efforts, including its translocation to Midway Atoll and Kure Atoll to establish additional populations. Coincidentally, also in 1923, another subspecies of Millerbird was discovered on Nihoa. Ironically, Laysan eventually would hold the best hope for fending off the potential extinction of the Nihoa Millerbird and restoring a lost element of the Laysan ecosystem.

A Plan Comes Together

Fast forward to 2007: Hawai‘i's avifauna had never been in a more precarious situation, and ABC, then only 14 years old, was modestly involved in conservation work in the state. We had campaigned to reduce bycatch of albatrosses in Hawaiian fisheries and poisoning of albatross chicks by lead paint peeling from Midway's World War II-era buildings, but we had not engaged on the conservation of Hawai‘i's many endangered forest birds or on the equally threatened seabirds nesting on the main Hawaiian Islands. We knew we should do more, and we set about identifying ways to add value to the work being carried out by Hawai‘i's small but dedicated cadre of state and federal agency biologists, university scientists, and nongovernmental organizations.

Two things leapt out: ABC could increase its fundraising for conservation efforts in the islands and raise awareness about the plight of Hawaiian birds. Along with colleagues at the Hawai‘i Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), we approached the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), one of the most important conservation donors in the U.S. This outreach led to NFWF developing its Hawai‘i Keystone Initiative. This would not satisfy all of Hawai‘i's funding needs — estimates of the cost of recovering just ESA-listed forest birds run into the billions of dollars — but it would be a huge step in the right direction. With guidance from Hawaiian conservation experts at DOFAW, FWS, and the U.S. Geological Survey, NFWF and ABC developed a 10-year business plan for the Keystone Initiative centered around raising awareness about Hawaiian birds and three species-specific projects, including translocating Nihoa Millerbirds to Laysan. The goal: to reduce the extinction risk by creating a second Millerbird population and restoring ecosystem function on Laysan by re-establishing Millerbirds there.

A single, isolated small population is at high risk of extinction. Worse, monitoring of Millerbird populations on Nihoa indicated that their populations fluctuated dramatically from year to year, ranging from approximately 194 individuals to 513. These population swings were apparently due to periods of drought and defoliation by non-native Gray Bird Grasshoppers. Due to these drastic swings in population, Nihoa Millerbirds are genetically very homogenous, probably limiting their long-term ability to adapt to environmental changes. A risk also existed that rats or other invasive species could accidentally be introduced to the island at some point in the future.

The science and ecology underpinning the Millerbird translocation had been completed, so NFWF and ABC's support combined with additional USFWS funding and regulatory approvals allowed the project to kick into high gear. Importantly, Sheila Conant, professor emeritus at the University of Hawai‘i-Mānoa, and her students and collaborators had already conducted much of the critical background research that was needed to plan a translocation, including studies of the ecology of the Nihoa Millerbird and assessment of habitat differences and similarities between Nihoa and Laysan that would inform a translocation. They had assessed the genetic differences between Laysan and Nihoa Millerbirds and found that they were sufficiently similar to each other to justify introducing the Nihoa birds to Laysan. Conant and her former student, Marie Morin, had also analyzed translocation options for passerine birds in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands that identified Laysan as the best option for the Nihoa Millerbird. And Mark MacDonald had just finished his thesis at the University of New Brunswick comparing invertebrate availability between the two islands and how to determine the sex of Millerbirds in the field (allowing us to select an even sex ratio in the translocation cohort).

A Lost Bird's Return

In addition, Laysan was ready to receive Millerbirds. FWS had spent over 20 years eradicating invasive, non-native plant species and planting native plants. The area of suitable habitat on Laysan was now several times larger than what existed on Nihoa, and introducing Nihoa Millerbirds would represent a continuation of Laysan's restoration by bringing back a lost member of its bird community.

The conservation project required a great deal of planning. The logistics of voyages to and from islands hundreds of miles from Honolulu were considerable. Permits for the project could only be granted after extensive agency review of our plans. And Nihoa and Laysan have strict quarantine regulations to prevent the accidental introduction of non-native organisms, so all our equipment had to be frozen to kill any insects that might be trying to join us; no fresh fruit or vegetables were allowed on either island; and we needed different clothing and equipment for each island.

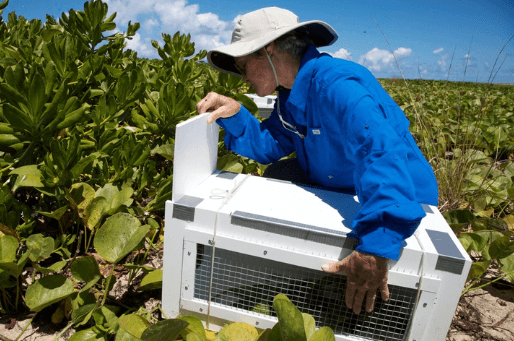

We conducted two rehearsal trips to Nihoa in 2009 and 2010 to capture test groups of Millerbirds and house and feed them in specially designed cages. Millerbirds eat live insects, so we had to make sure we could keep them healthy on frozen and dried foods for up to 10 days — the maximum amount of time we thought we would need to capture the birds on Nihoa, transport them to Laysan, and prepare them for release. Landing at Nihoa was half the battle, since the island is rocky with tall cliffs and has only one suitable landing site. Everything we needed to house Millerbirds and ourselves had to be ferried to the landing site by Zodiac. Getting on the island is a matter of timing the swells and jumping, and sometimes falling, onto slick rocks. A steep, but short, climb up leads to a hollow in the rocks where we established a shaded camp and a site for a bank of Millerbird cages. We distributed traps to capture flies to supplement the captive birds' diet. We were constantly surrounded by the traffic and din of seabirds including noddies, frigatebirds, terns, petrels, and shearwaters. Nihoa Finches fluttered by on stubby wings and nosed about in the soil. In short — it was magical.

We found Millerbirds in dense ‘ilima and pōpolo shrubs and coaxed them into short, very fine, nearly invisible mist nets about 8 feet long using playback of their song. We then disentangled them and brought them to the holding cages in individual transport boxes where aviculturalists Peter Luscomb of Pacific Bird Conservation and Robby Kohley of ABC looked after their care and feeding. Millerbirds are very plain and the sexes resemble each other, but they can be distinguished by subtle differences in their wing and tail measurements. It was common for birds to lose weight during their first 24 hours in captivity and then to rapidly gain it back as they became accustomed to receiving fresh flies and the frozen waxworms that we had brought with us. The trials were highly successful and gave us confidence that we could keep the Millerbirds alive. The lingering concern was the nearly 650-mile voyage to Laysan. The birds would be in a cabin below deck for over three days. We had no idea how they would respond to the confinement, lighting, air flow, and, above all, motion, which could be considerable if seas were rough. We timed the translocations for the calmest months of August and September, but nothing was assured.

With some practice under our belts, permits in hand, and gear organized, we departed Honolulu on September 2, 2011, for the first translocation. We arrived at Nihoa after a 300-mile, 31-hour voyage late on September 3. The next day, we set up camp and got to work capturing Millerbirds using the same techniques employed during our rehearsal trips. During September 4-6, we captured 33 Millerbirds and selected 24 for translocation, 13 males and 11 females, all of which were banded with a unique combination of colored leg bands. On September 7, we made a human chain to pass the holding cages down the steep trail to the awaiting Zodiac, bringing us back to where this story began.

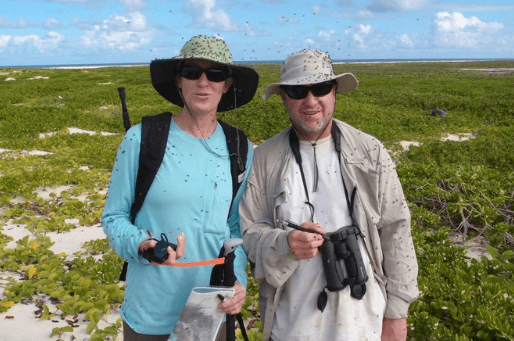

Our ethereal voyage concluded late on September 9, when we arrived at Laysan, just as tens of thousands of Bonin Petrels were converging on the island. The next day, we got to do what we had been working toward and visualizing for years. The Millerbirds had all survived and were transferred to their Laysan holding cages, transported by Zodiac to the FWS camp on the island (a much easier landing on gentle sand!), and prepared for release. Laysan is a completely different island from Nihoa — no less magical, but strikingly different. Laysan is flat and sandy with a central saline lake surrounded by a halo of vegetation and low dunes. Like Nihoa, seabirds dominate the scene, but unlike Nihoa, delicate seabird burrows pockmark the landscape, making walking extremely tricky and incredibly stressful. Laysan has its own finch, and they are bolder and more inquisitive than the Nihoa Finches.

A Momentous, Inspiring Accomplishment

Laysan is teeming with flies. Their loud hum across the entire island is the first thing you hear in the morning before the seabirds wake up. A person's body is always covered with flies as they explore every patch of exposed skin, including lips, eyes, nose, ears — nothing is spared. As 12 Millerbirds were fitted with radio transmitters for post-release monitoring, they captured flies right off our hands. The birds were definitely not going to have any trouble finding food! We carried the birds in special cages and released them into the wild in a large patch of dense naupaka, a native shrub, at the northern end of the island.

Patterned after the first translocation, we conducted a second journey with 26 birds in August 2012, bringing the total released to 50. On the second translocation, Conant, who had devoted so much of her career to the study of Millerbirds, was able to join the expedition and release birds onto Laysan — literally a dream come true. The new Laysan population of Millerbirds was monitored continuously through fall 2014. Almost immediately, it was apparent that this new population was destined to succeed as the birds started breeding less than a month after the initial 2011 release. Monitoring has been difficult in recent years due to reduced funding, but the last full survey in 2019 found Millerbirds have expanded across the island with an estimate of over 300 birds, and quicker spot trips have confirmed the birds are continuing to thrive on Laysan. (Note: A June 2024 report revealed promising news about the Millerbird: Approximately 600 individuals have been spotted on Laysan and another 1,200 on Nihoa.)

It's difficult to overstate how momentous the successful establishment of a Millerbird population on Laysan is among Hawaiian and global conservation efforts. Its success is testament to the value of deep background preparation and planning and a passionate team with diverse expertise. In the context of Hawaiian bird conservation, it is inspiring at a time when so many Hawaiian birds are teetering on the brink, and it provides a template for future translocations that could be undertaken for other species, such as the Nihoa and Laysan Finches.

In the global context, it stands out as among the most logistically complex avian translocations ever attempted, and our experiences could aid in translocations of other island species, in particular other threatened birds closely related to the Millerbird (Acrocephalus reed warblers). IUCN's downlisting is an acknowledgment that the risk of extinction has been significantly reduced. Sadly though, we realize that the new Laysan population may not be enough to safeguard the Millerbird indefinitely into the future. Laysan will be relatively safe for sea level rise for over 100 years, but it is still a low island and therefore vulnerable to catastrophic weather, including hurricanes or over-wash by ocean waves due to climate change. For this reason, the Millerbird's status under the ESA is not likely to change anytime soon. However, our team's work has restored a critical component of the Laysan ecosystem and given the Millerbird time and hope for the future.

The Millerbird translocation project was led by FWS, co-manager of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, in collaboration with ABC. We are grateful for the participation and support of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the University of New Brunswick, University of Hawai‘i, Pacific Bird Conservation, Pacific Rim Conservation, the USGS National Wildlife Health Research Center, and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

We're grateful to each of the 26 people who made up the translocation crews. They're listed here alphabetically with their affiliations in 2011-12; names of repeat members are in italics.

2011 Laysan crew

- Michelle Cuter, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- Chris Farmer, ABC

- Holly Freifeld, USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office

- Lauren Greig, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- Robby Kohley, ABC

- Peter Luscomb, Pacific Bird Conservation

- Rachel Rounds, USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office

- Cameron Rutt, ABC

- Tawn Speetjens, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- Matt Stelmach, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- George Wallace, ABC

- Thierry Work, USGS-National Wildlife Health Center

2011 Nihoa crew

- Walterbea Aldeguer, Office of Hawaiian Affairs

- Fred Amidon, USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office

- Daniel Tsukayama, ABC

- Eric VanderWerf, Pacific Rim Conservation

2012 Laysan crew

- Toni Caldwell, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- Sheila Conant, University of Hawai‘i-Mānoa

- Ryan Hagerty, USFWS National Conservation Training Center

- Claudia Mischler, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- Amy Munes, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- Sheldon Plentovich, USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office

- John Vetter, ABC

- Michelle Wilcox, ABC

- Chris Farmer, ABC

- Robby Kohley, ABC

- Peter Luscomb, Pacific Bird Conservation

- Tawn Speetjens, USFWS-Hawaiian Islands NWR

- Thierry Work, USGS-National Wildlife Health Center

2012 Nihoa crew

- Kevin Brinck, US Geological Survey-Hawaiian Cooperative Studies Unit

- Annie Marshall, USFWS-Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office

- Walterbea Aldeguer, Office of Hawaiian Affairs

- Daniel Tsukayama, ABC

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of Bird Conservation. Become a member to receive ABC's magazine, published three times per year, and enjoy other benefits like exclusive members-only events and discounts for bird-friendly coffee from our partners at Birds & Beans Coffee.

About the Authors

| George E. Wallace recently retired after 18 years with ABC; in that time, he served as Vice President for International Programs, Vice President for Oceans and Islands, Chief Conservation Officer, and Director of International Programs and Partnerships. He is now an ABC Ambassador. |

| Chris Farmer, ABC's Hawai‘i Program Director, has worked on bird conservation in the state for 20 years. |