Forests at Work for People and Birds

This is part of a series of explorations of different kinds of forest biomes found throughout the Western Hemisphere – and how American Bird Conservancy works to conserve them as vital bird habitats. Click to read about tropical forests, temperate forests, boreal forests, and different ages of forests.

For many birds, forests are nest sites and nurseries, territories, and rest stops. They provide the abundant resources that help birds survive and raise their young successfully.

They do much of the same for people. Forests perform many essential ecosystem services that go unnoticed, like absorbing carbon from the atmosphere and using their vast networks of roots to stabilize soil and prevent erosion. From forests comes the wood that frames our homes, medicines that sustain our health, and many foods we eat. Forests are also places where we can enjoy ourselves, nurture our curiosity, and experience awe.

While some forests — like the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest — must be protected, other forests thrive with sound management principles applied. From the Andes in South America to Appalachia in the United States, American Bird Conservancy (ABC) and our partners are finding ways to manage forests to fulfill the needs of people while creating and enhancing valuable habitat for birds.

Brewing a Plot for Birds and Coffee to Co-Exist

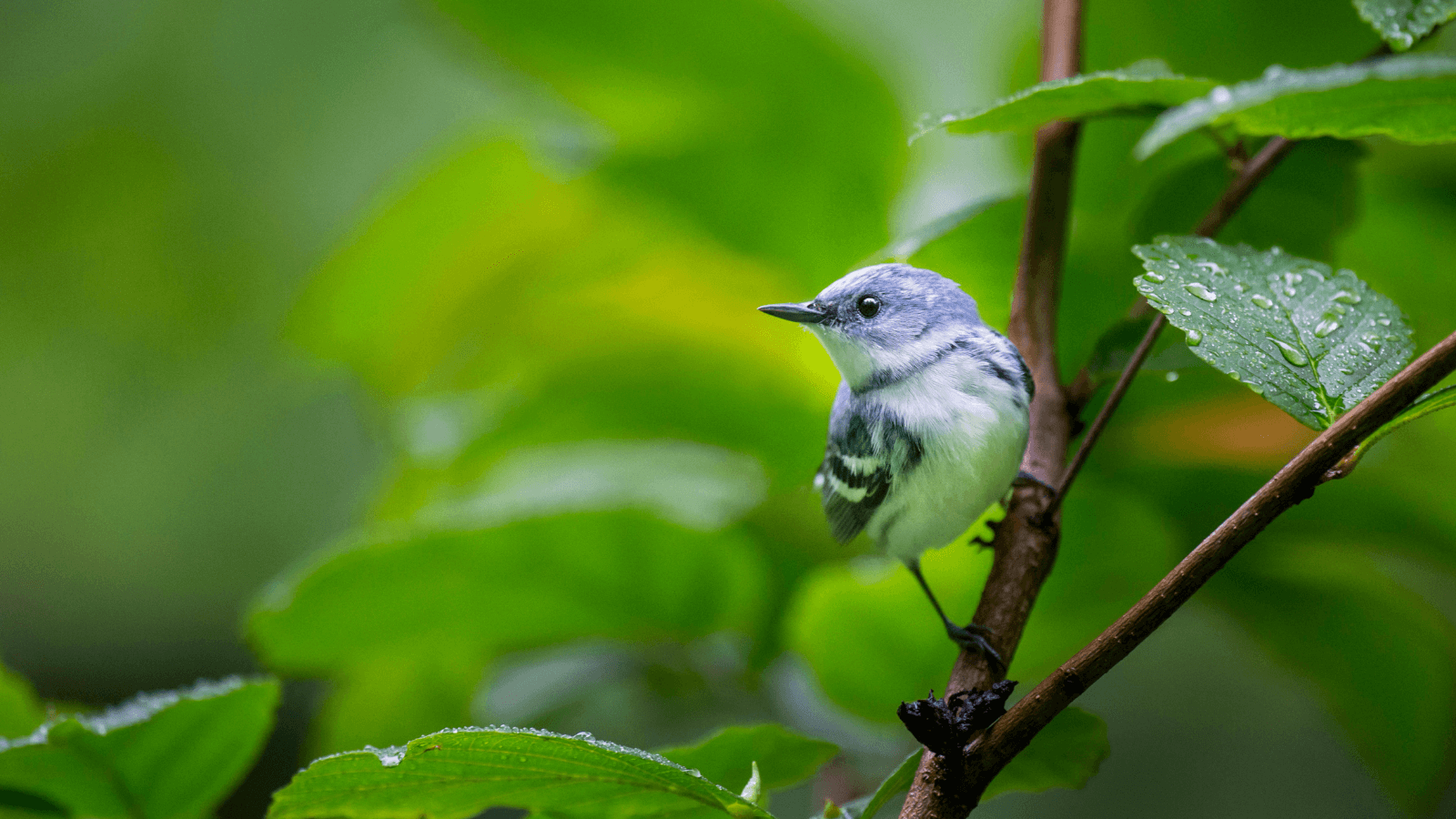

On either end of their migration, and in places in between their breeding and nonbreeding grounds, migratory birds like the Golden-winged Warbler often find that the forests that once supported them no longer do so. The unrestrained clearing of land for housing and shopping centers contributes to habitat loss on the breeding grounds, while on the nonbreeding grounds, unsustainable cattle grazing or agriculture might be the cause. People have needs, of course, but when bird habitat declines, people suffer, too. Clearing land to plant vast monoculture crops like coffee and cacao (the beans that are roasted to become cocoa) or to make room for cattle grazing can lead to more frequent mudslides and less shade to offer refuge from increasingly hot temperatures.

Cutting out coffee would be inconceivable for coffee growers and coffee lovers around the world. So, ABC has supported and launched initiatives to help the land work for everyone, building on the idea of improving working lands for birds with a healthy mix of native trees and shrubs. ABC's BirdsPlus program connects people on working lands to opportunities to unlock funding streams as they implement best management practices to create or enhance bird habitats.

ABC is investing in agroforestry throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, helping farmers and ranchers improve their operations, livelihoods, and the habitats that birds need. As the habitat improves for migratory birds, the native trees add nitrogen to the soil and prevent erosion. This also creates a richer soil that produces high-quality, flavorful coffee, cacao, and even spices, such as cardamom, ginger, and turmeric. Rubber can also be grown this way. It all happens while maintaining a vital source of income for many families.

When you sip a piping-hot cup of certified Bird Friendly® coffee, you are getting more than a quick pick-me-up. Things get even sweeter with certified Bird Friendly® cocoa products. ABC has supported the launch of the first-ever line of chocolatey treats grown with bird-friendly principles in mind. In the Dominican Republic, where the first line of Bird Friendly® cocoa was grown, that's a sweet deal for the wintering Bicknell's Thrush and Black-throated Blue Warbler along with native species like the tiny Broad-billed Tody.

Forests at Work in the Appalachian Mountains

When they return to their breeding grounds during spring in the Northern Hemisphere, Golden-winged Warblers rely on a mix of forested brushland or young forest patches for nesting. Once they have fledged the nest, however, these young warblers need older deciduous trees for foraging. That combination of habitats can be hard to come by, particularly in Appalachia, where the species has declined by 96 percent. The outlook is slightly better for the population of Golden-winged Warblers in the Great Lakes region, but the species is still considered Near Threatened by the IUCN.

Private landowners can be some of the best allies in the effort to create inviting, healthy bird habitat in Appalachia and the Great Lakes region. The ABC-administered Appalachian Mountains Joint Venture (AMJV) and ABC's Great Lakes Program work with landowners to help them realize the potential for their land as bird habitat and as a working forest.

The disturbances that once created the dynamic habitats that Golden-winged Warblers need, such as periodic fire, have largely been brought under control. The result is a relatively uniform landscape with similarly aged trees in the place of a diverse forest populated with trees of different ages and sizes with natural gaps in the canopy that let in light for the plants below. In addition to inviting far fewer birds, a lack of diversity in a forest can also make it more susceptible to non-native plant species creeping in and doing serious damage to native trees. That's bad news for the trees and the birds, like the Cerulean Warbler, that need them.

The good news is that forests can be carefully managed to restore and maintain their health and maximize their benefit to birds. They can also be intentionally managed to allow for the simultaneous, sustainable harvest of timber. To breathe color and life into relatively quiet and monotonous forests, foresters can employ a number of techniques, including thinning. Harvesting some taller trees while leaving others standing opens up the canopy, making it possible for light to reach the plants on the ground. After several years of understory growth and the removal of the tallest and most valuable trees without compromising forest health (a process called high-grading), a homogeneous forest with little to offer wildlife begins to turn into a dynamic and lively habitat, with a mix of older and younger trees, new vegetation growth at the ground level, and more birdsong in the air from resident species and migratory birds, including Golden-winged Warblers.

The working forest model works for birds and landowners, who can sustainably harvest trees and generate income while maintaining a healthy habitat. Programs exist to provide financial incentives and cost-sharing support to encourage sustainable forest management, whether strictly for conservation purposes or as part of a working forest management plan. In Appalachia, the owners of working forests get another kind of incentive, too: the appearance of the flashy, yellow-streaked Golden-winged Warbler in the spring, often accompanied by other species passing through or setting up for the breeding season, including the American Woodcock, Common Yellowthroat, and Indigo Bunting.

High Hopes for Swallow-tailed Kites

The U.S. population of the graceful and iconic Swallow-tailed Kite nosedived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Unsustainable logging of the nesting habitat favored by kites — humid bottomland forests and riparian forests along rivers and streams — led to a contraction of the raptor's breeding range. The Swallow-tailed Kite nested in 21 states in the U.S. in decades past, but today, they are known to nest in a mere seven states in the Southeast. Slowly, their numbers are ticking up and these distinctive, fork-tailed flyers are a more frequent sight in the skies.

Working forests are part of the solution to bringing kites back. The Swallow-tailed Kite needs stands of tall trees for nesting with open areas close by for grabbing food for their nestlings. As it turns out, sites of recent timber harvests create the conditions nesting kites need.

Through a partnership with ABC, South Carolina-based International Paper (IP) is now sourcing trees for its products from sustainably managed forests. IP produces the fluff pulp used in diapers, toilet paper, and other daily necessities in high demand. While IP doesn't own forestlands, it does contract with landowners to purchase timber. As a member of the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), IP buys wood only from farms that meet SFI's high sustainability standards, which include landowners taking steps to conserve birds and other wildlife. IP's commitment sets the bar higher for owners of timber farms. The partnership is working as more landowners adopt best practices, and that's a good thing for the Swallow-tailed Kite and the sky-high nesting trees it needs.

In Working Forests, a Mutually Beneficial Relationship

Models of working forests from Latin America, Appalachia, and the Southeastern U.S. show that in some places, creating a habitat where birds can thrive doesn't have to come at the expense of human needs. In fact, both can benefit when the right science-backed management techniques are applied in the right places – ensuring the conservation of prime bird habitat and the sound care of the forest's overall health for the long term.

Interested in learning how your forested property can help to meet conservation aims? Your region's Joint Venture can offer guidance on getting started. Watch our webinars on the Southeast's working forests setting the stage for a Swallow-tailed Kite comeback and on the sweet deal bird-friendly chocolate can offer farmers and migratory birds, and discover how you can choose bird-friendly products, too.

This is part of a series of explorations of different kinds of forest biomes found throughout the Western Hemisphere – and how American Bird Conservancy works to conserve them as vital bird habitats. Click to read about tropical forests, temperate forests, boreal forests, and different ages of forests.