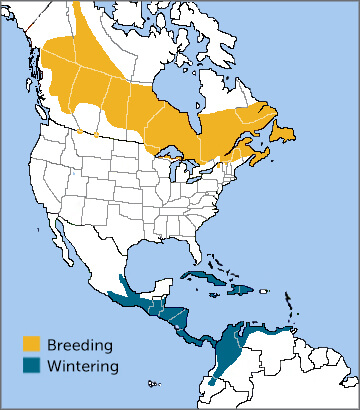

Tennessee Warbler map by ABC

The small, spritely Tennessee Warbler, like the Cape May Warbler, is poorly named. Although both species pass through their namesake locales, neither is “typical” of those places. The Tennessee Warbler has never bred in Tennessee, but was named for the state by ornithologist Alexander Wilson, who collected the first “type-specimen” there in 1811, no doubt during migration.

Unlike many of its brightly colored relatives, the Tennessee Warbler has an understated beauty. A spring male sports a blue-gray crown that contrasts its olive-green back and white undersides and undertail. It has a dark line through the eye and a white eyebrow line above.

This warbler could easily be mistaken for a Red-eyed Vireo, but is smaller, shorter-tailed, and markedly more active. Also, it has a thin, pointed beak, in contrast to the vireo's rather thick, slightly hooked bill.

The female Tennessee Warbler looks similar to the male, but is more muted in coloration. Fall birds are washed with yellow on the breast and undersides, so the gleaming white undertail feathers (coverts) stand out in most individuals. Juveniles look quite yellow during their first fall, but still show the characteristic light eyebrow and undertail.

The Tennessee Warbler's species name peregrina comes from the Latin word peregrinus, which means "wanderer." This small Neotropical migrant, like many of its near-kin, undertakes long journeys twice a year between its breeding and wintering grounds, spending several months on the move.

Many more descriptive, accurate names could describe the Tennessee Warbler. One name, which refers to one of this bird's favorite winter habitats, also gives a nod to its jittery ways.

Coffee Warbler

The Tennessee Warbler favors open woods during the winter, habitat that is provided by shade-coffee plantations in Central and northern South America. In fact, this little songbird is so common in these habitats that tropical ornithologist Alexander Skutch suggested that a more apt name for the Tennessee Warbler would be the “Coffee Warbler.” This warbler's zippy foraging behavior also supports this name — or perhaps, the “Caffeinated Warbler” might work?

Molting Mid-Migration

The Tennessee Warbler breeds in boreal forests across much of Alaska and Canada, and in some spots in the lower 48 states just south of the Canadian border. Across much of this breeding range, it is one of the most abundant warblers. This species winters in the tropics, from southern Mexico and parts of the Caribbean to northern South America. Unusual among North American songbirds, the Tennessee Warbler begins its southward migration while still molting. (Most finish molting before they migrate.)

One of the Tennessee Warbler's most notable features is the male's loud, staccato, two- or three-part song. Only the males sing; their persistent vocalizations can be heard during migration, as well as on the breeding grounds.

Listen here:

(Audio: Richard E. Webster, XC189620. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/189620)

Fierce Feeder

The Tennessee Warbler is an active forager, making short forays to the outer areas of trees and shrubs to glean food with its thin, sharp-tipped bill. Like the Bay-breasted Warbler, the Tennessee is a spruce budworm specialist, and its numbers rise and fall depending on that insect's abundance, sometimes drastically. During budworm outbreaks, densities of singing males can be as high as two per acre, only to plummet the following year. Other small invertebrates are sought as well, including beetles, grasshoppers, aphids, and spiders. During migration and winter, this warbler adds nectar and fruit to its diet, a flexible feeding strategy used by many other Neotropical migrants ranging from the Baltimore Oriole to the Scarlet Tanager.

Immature Tennessee Warbler in the fall. Agami Photo Agency, Shutterstock

Tennessee Warblers join mixed-species flocks during migration, mingling with other warblers, grosbeaks, and buntings, as well as residents such as the Black-capped Chickadee, Golden-crowned Kinglet, and White-breasted Nuthatch. This social structure persists during the winter, when Tennessee Warblers associate with a wide variety of other bird species around flowering trees and other nectar sources. This songbird fiercely defends its feeding territory, chasing off members of its own species as well as other birds.

Mossy Nester

Like most North American wood-warblers, the Tennessee Warbler is seasonally monogamous, remaining with one mate per breeding season. Males are very territorial and defend their territories with vigorous and persistent song.

Once mated, the female builds a well-concealed, cup-shaped nest on the ground in a clump of sphagnum moss, or at the bottom of a small tree or shrub. She sits tight on the nest and will only flush if very closely approached. The female spends the most time brooding the eggs and hatchlings. The male helps to feed the young, both in the nest and after they fledge.

Widespread but Worth Watching

Although the Tennessee Warbler is a common species, it contends with the same threats facing scarce birds, particularly habitat loss and fragmentation on breeding and wintering grounds. In addition, it is a frequent victim of collisions with glass, towers, and wind turbines.

ABC provides a number of resources to help reduce these threats. We are involved in a number of large-scale initiatives that conserve and recover habitat on breeding and wintering grounds, including BirdScapes, Joint Ventures, and Southern Wings. Our collisions program helps to prevent communications tower collisions and fatalities, and provides solutions to prevent bird collisions with glass, particularly at home windows.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!