Envisioning the Next 30 Years of Bird Conservation

This year is American Bird Conservancy's 30th anniversary year. Thirty years from now, if I am still alive, I will be 92 years old. And if I am lucky, I will then be looking back on 60 years of ABC's progress to conserve the birds of the Americas. What would need to have happened over these next three decades to make me feel that we had succeeded in our work? This seems like an opportune time to look forward, and perhaps some of these thoughts will inspire you too to consider what you would like to see happen for birds in the coming decades.

First and foremost, we cannot conserve bird species if we cannot find them. So, the first order of business is to try to locate the 125 or so of Earth's bird species that are not yet definitely extinct but have not been observed by anyone in ten or more years at the time of this writing. Can we find half of them? If we can, I think we will have made substantial progress.

Next are the birds that now exist only in captivity (categorized as Extinct in the Wild or EW). There are just a handful of such species, and all are in fact from the Americas or U.S. territories. One of them is in Hawai‘i, the ‘Alalā or Hawaiian Crow; then there is the Socorro Dove of Mexico, and the Alagoas Curassow of Brazil. The Sihek, or Guam Kingfisher, was recently released back to the wild on Palmyra Atoll, and despite a huge series of challenges, Spix's Macaw is again breeding in the wild in Brazil after many years only in captivity. Is it too much to hope that all the current EW species could again be breeding in the wild by 2054?

The next group of birds I think about are those that are currently considered Critically Endangered or Endangered in the wild. In the U.S., most of these are also in Hawai‘i. ABC is currently involved in an ambitious project to prevent the extinction of these species by reducing the populations of introduced mosquitoes that are spreading avian malaria to native forest birds. If we succeed, in 30 years, the project will have become effective and self-sustaining, allowing native bird populations to recover and expand. Some may even develop tolerance of malaria as the Hawai‘i ‘Amakihi has already done.

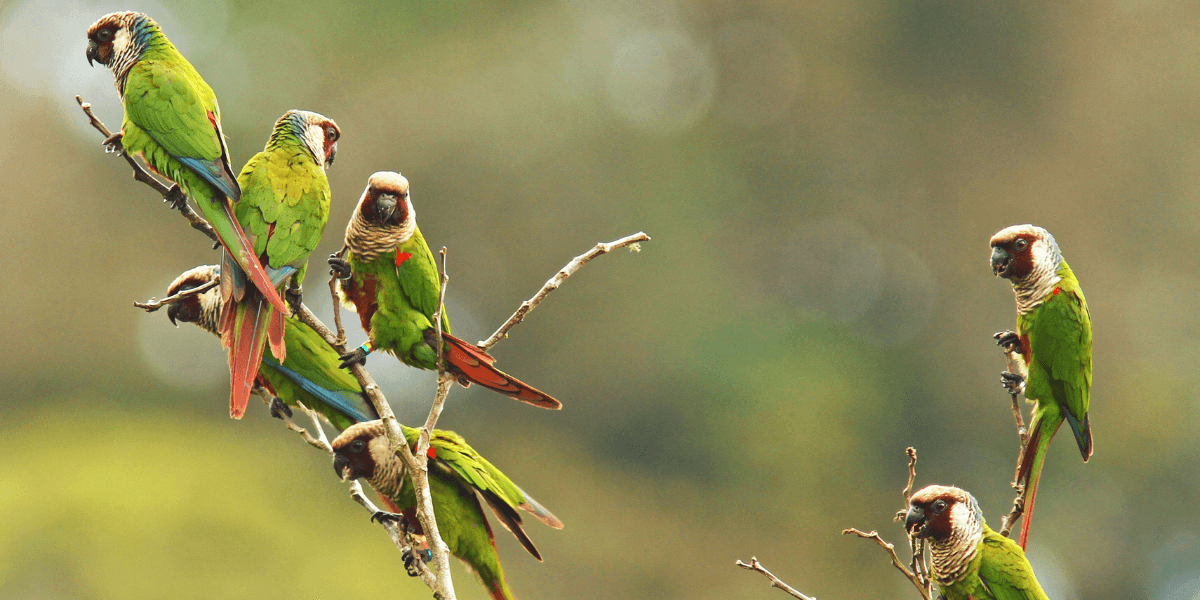

Elsewhere in the hemisphere, we need effective protected areas that provide habitat for all endangered birds. ABC and our partners have made major progress already, with more than 100 bird reserves providing habitat for more than 80 of the Americas' most endangered birds, such as the Santa Marta Parakeet and Long-whiskered Owlet. This goal should be achievable within a decade or two, perhaps even sooner. Unfortunately, seabirds, which are also highly threatened, are impacted by both climate change and invasive predators. Realistically, we are going to need to protect more nesting colonies with predator-proof enclosures well above sea level (to avoid the rising oceans) for many of these species. For others that exist on uninhabited islands with fewer biosecurity issues, we can conserve them by continuing to implement full-island predator eradications, a practice used for decades and known to be effective. Perhaps by 2050 we can see all the most vulnerable seabird species protected through these methods.

For declining birds that are not yet endangered, like the Golden-winged Warbler and Cerulean Warbler, diversifying habitats is the key. To bring back these birds — and reverse the loss of 3 billion of North America's birds since 1970 — we have to address the fact that North American habitats have become less diverse over time. Too many forests in the east and west are evenly aged, and too much grassland in the center of the continent is evenly grazed, all of which supports less biodiversity and fewer birds.

By 2054, we need to have demonstrated that we can create more diverse forest and grassland systems that can bring birds back, and we need to be in the process of scaling conservation up across a much larger area. If we could first halt declines, then begin a turnaround with a 1-2 percent annual increase, we could potentially return birds to their former abundance by 2100.

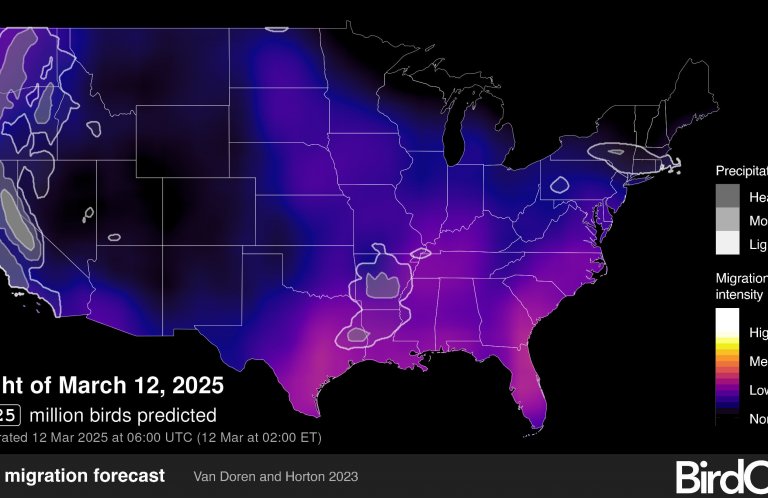

For migratory birds, we are going to need similar progress on wintering grounds, too, and supporting the transition to more sustainable agricultural landscapes in Latin America is critical to this (in addition to expanding protected areas as I mentioned earlier). For example, both coffee and cacao can be grown beneath tree canopies that provide bird habitat. Expanding these and other agricultural practices is an important way to improve bird habitat while capturing carbon as well.

There is more, of course — much more we need to do over the next 30 years, including building a broader future constituency for bird conservation, countering the effects of climate change on bird habitat, and reducing threats to birds such as window collisions and pesticides. And I'll save those considerations for a future column.

More than anything, right now, we need to pull together and support the growth of bird conservation this year and next — so we can build a solid platform to move all these accomplishments forward for the future. Your end-of-year gift would go a long way to helping make this vision of a better future for birds a reality!

Thank you for all your help.