3 Billion Birds Lost: A Visual Journey

The news that an estimated 2.9 billion breeding birds have been lost from the U.S. and Canada since 1970 may seem overwhelming. To help make sense of this decline and better understand what it means for birds, we and our partners have prepared a series of infographics that highlight impacts on five highlighted bird groups.

Read on to learn more, and find out how American Bird Conservancy is responding to the situation.

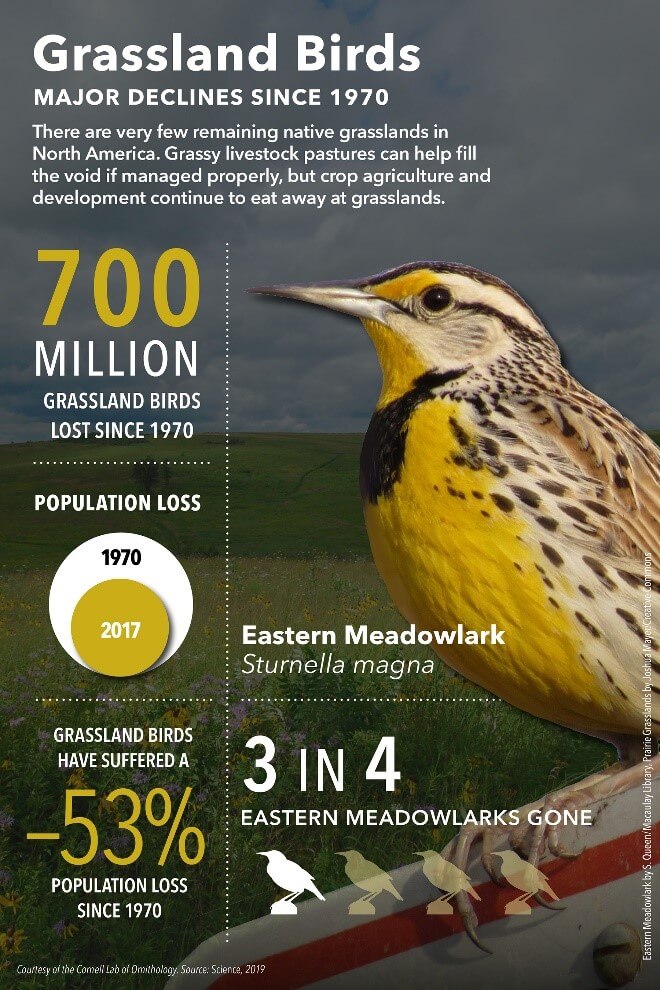

Grassland Birds

The Northern Great Plains have changed dramatically since the 1800s, with the conversion of 51.3 million acres of grasslands to cropland agriculture, resulting in dramatic losses for grassland birds, which have been affected more than any other bird group.

The Northern Great Plains have changed dramatically since the 1800s, with the conversion of 51.3 million acres of grasslands to cropland agriculture, resulting in dramatic losses for grassland birds, which have been affected more than any other bird group.

In this region, ABC is assisting private landowners in efforts to enhance grassland bird habitat, while helping maintain ranchers' livelihoods.

Roughly 85 percent of grassland bird species that breed in the Northern Great Plains of the United States spend their winters in the Chihuahuan Desert, which suffers from long-standing habitat concerns.

Conservationists are combating these challenges in both regions, and new approaches to cattle grazing are among the solutions: By strategically moving cattle from pasture to pasture, livestock can mimic the positive effects that bison had on the landscape centuries ago.

So far, American Bird Conservancy and Mexican partner organization Pronatura Noreste have improved habitat for birds on nearly 70,000 acres of working lands in an area known as the Valles Centrales.

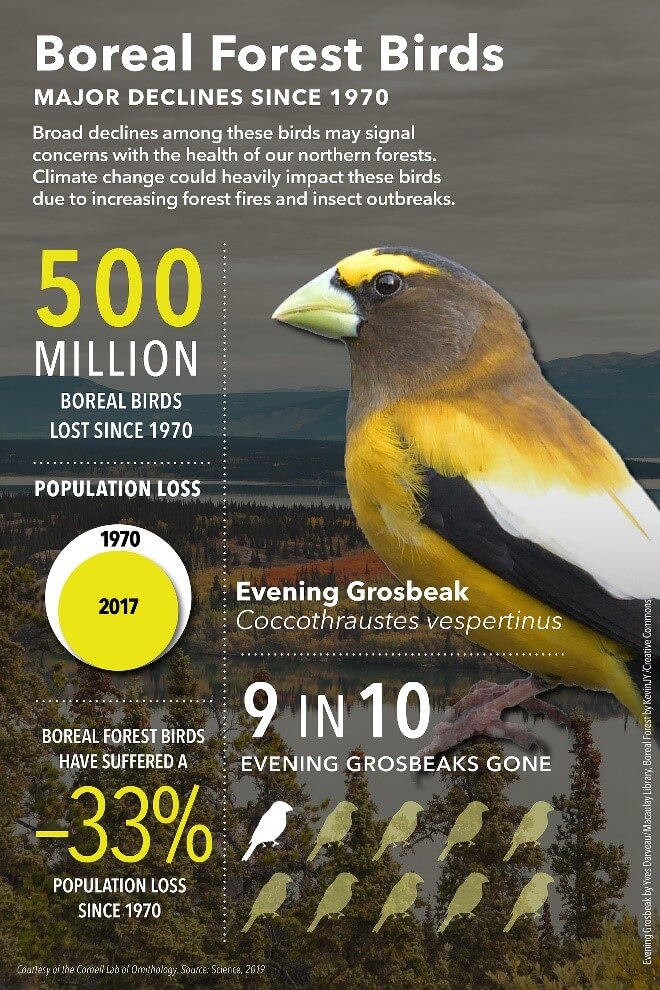

Boreal Forest Birds

Climate change is having a significant impact on birds in the Americas, both on species of conservation concern and those still considered common and non-threatened.

Climate change is having a significant impact on birds in the Americas, both on species of conservation concern and those still considered common and non-threatened.

Solving this problem will be a conservation focus for decades to come. American Bird Conservancy is working to reduce the impacts of climate change on birds and their habitats, and to ensure that all birds of the Americas maintain healthy and vigorous populations into the 22nd century and beyond.

Climate change exacerbates existing risks to birds, such as degradation or loss of habitat and the spread of invasive species.

Coastal habitats, such as those critical for breeding Mangrove Hummingbirds in Costa Rica and nesting sites for many seabirds and coastal marsh birds, are expected to be affected by sea level rise. As temperatures warm, the high mountain forests in Hawai‘i that are home to birds like the 'I'iwi are experiencing an influx of introduced pests, especially lethal illnesses transmitted by introduced mosquitoes.

More frequent and severe weather events may further stress bird populations. Changes in climate patterns, for example, can upset the synchronization of bird migrations, such as the arrival of Red Knots at traditional stopover feeding grounds on Delaware Bay, which traditionally happens when horseshoe crab eggs are most abundant.

The destruction of forests releases carbon and hastens climate change. Studies show that deforestation accounts for 14 percent of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Conversely, reforestation and preventing deforestation are two actions we can take to slow climate change. Many of ABC's bird conservation projects protect carbon-rich tropical forests. For example, by creating or expanding 90 bird reserves, we have protected over 1 million acres, keeping forest carbon in the ground.

ABC's tree-planting efforts restore forests that help to keep our climate stable. In one area of Peru alone, more than 1 million trees have been planted with ABC's help. Across Latin America and Hawai'i, our reforestation efforts have resulted in the planting of 3.6 million trees and shrubs.

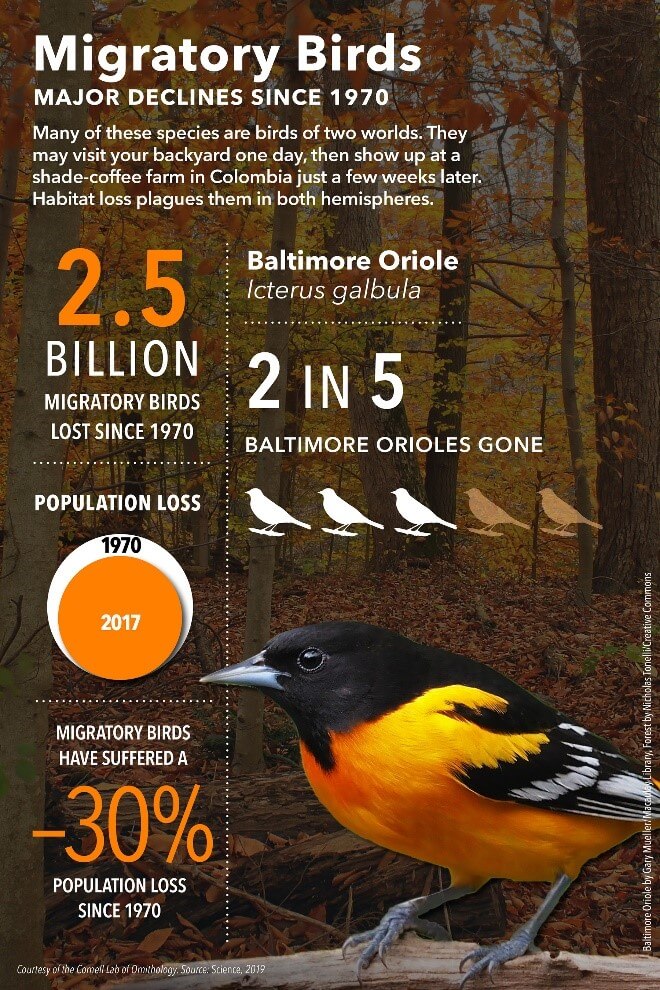

Migratory Birds

Some migratory birds, such as the Red Knot, traverse the entire Western Hemisphere twice each year, from Patagonia to the Arctic and back. Weighing only 16 grams — the weight of two quarters — the Blackpoll Warbler and other warblers cross thousands of miles of open ocean en route to wintering then breeding grounds. And the tiny Ruby-throated Hummingbird crosses the Gulf of Mexico, flying non-stop for 24 hours. Other birds island-hop across the Caribbean, and millions upon millions pour north out of Central America in spring before fanning out to breed across Canada and the United States.

Some migratory birds, such as the Red Knot, traverse the entire Western Hemisphere twice each year, from Patagonia to the Arctic and back. Weighing only 16 grams — the weight of two quarters — the Blackpoll Warbler and other warblers cross thousands of miles of open ocean en route to wintering then breeding grounds. And the tiny Ruby-throated Hummingbird crosses the Gulf of Mexico, flying non-stop for 24 hours. Other birds island-hop across the Caribbean, and millions upon millions pour north out of Central America in spring before fanning out to breed across Canada and the United States.

There are several reasons why birds migrate, but in general it's because of food, specifically insects and nectar. In winter, over much of the U.S. and Canada, these foods become much more scarce or unavailable. That means many species must fly to other places (usually well to the south) to continue finding meals.

Many people quip that they'd prefer a world without “bugs,” but as the adage goes: Be careful what you wish for. Our planet cannot function normally without insects and other invertebrates. For example, except for seabirds, virtually all North American birds feed insects to their young. Scientists believe agricultural alchemy plays a big role in insect declines. Pesticides cast a broad yet invisible shadow over huge swaths of land, often well beyond areas they are meant to treat.

Today, the world's most widely used agricultural pesticides are neonicotinoids, neurotoxins absorbed and stored in plant tissues to repel insect pests. Via dust and in water, these long-lasting chemicals frequently spread far beyond crop areas where they are initially distributed. And although these insecticides are considered less dangerous to many vertebrates than are other pesticides, an ABC study in 2013 determined that a single neonic-coated seed can kill a bird the size of a Blue Jay.

ABC and other groups are also calling for a ban on the use of chlorpyrifos. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) scientists agreed that there is no way to use the pesticide safely, and the agency was on course to ban it in spring 2017. But EPA reversed course, extending its use for five years. In July 2019, EPA rejected a challenge by a coalition of environmental and public health advocacy groups that urged the agency to ban the pesticide. ABC and others continue to advocate for legislation prohibiting chlorpyrifos' use. Meanwhile, states are taking action: California, Hawai‘i, and New York have initiated bans, and a few other states may soon follow.

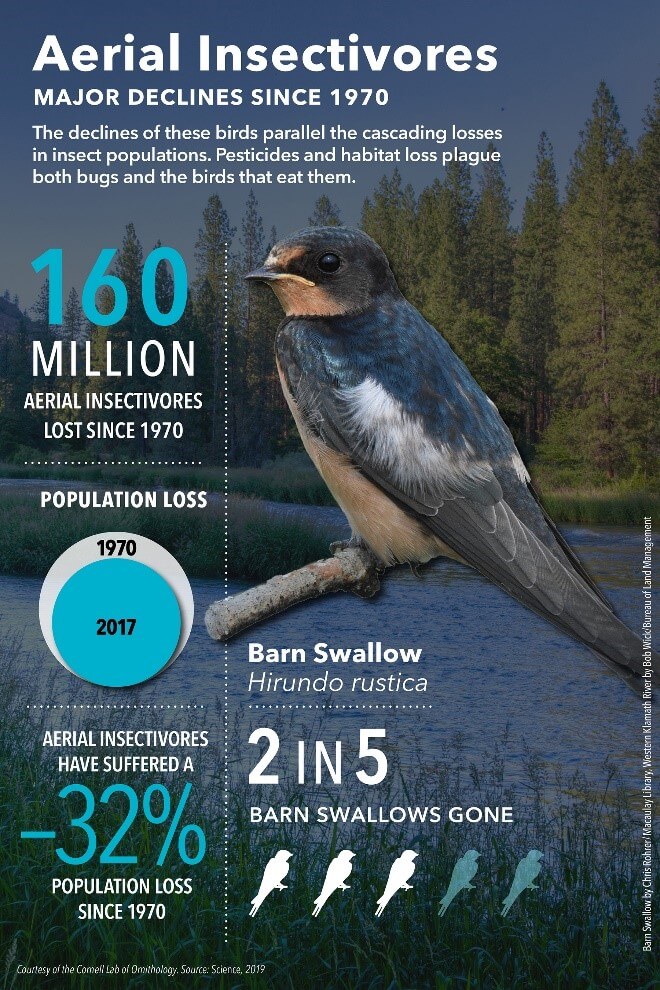

Aerial Insectivores

Aerial insectivores such as swallows and swifts feed almost exclusively on the wing. It doesn't look like habitat, but for these animals, the air is home, where they spend much of their lives. And as researchers are learning, what happens there carries life-or-death consequences.

Aerial insectivores such as swallows and swifts feed almost exclusively on the wing. It doesn't look like habitat, but for these animals, the air is home, where they spend much of their lives. And as researchers are learning, what happens there carries life-or-death consequences.

Knowing how birds use airspace helps drive ABC's work to minimize the dangers posed by wind turbines and communications towers. Aeroecology, the study of airspace as habitat, helps researchers and conservationists understand what happens to those birds in the air and how easy or safe it is to move from one location to another.

Even birds that don't catch dinner on the wing must deal with airspace issues. “We spend a lot of time studying birds on the ground, but they have to go from one place on the ground to another place on the ground. And the way they get there is, of course, by flying,” says Christine Sheppard, Director of ABC's Glass Collisions Program. “It exposes them to so many threats.”

Birds can't see glass unless it's modified to incorporate specific patterns or designs. In the U.S. alone, up to 1 billion birds a year die when they fly into windows of office buildings and homes. Others fall victim to communications towers and related guywires, which in the U.S. kill an estimated 7 million birds a year. That number should begin to decline as tower operators switch from steady-burning to blinking lights that are less disorienting for birds — thanks to a change in Federal Communications Commission guidelines that ABC helped to bring about.

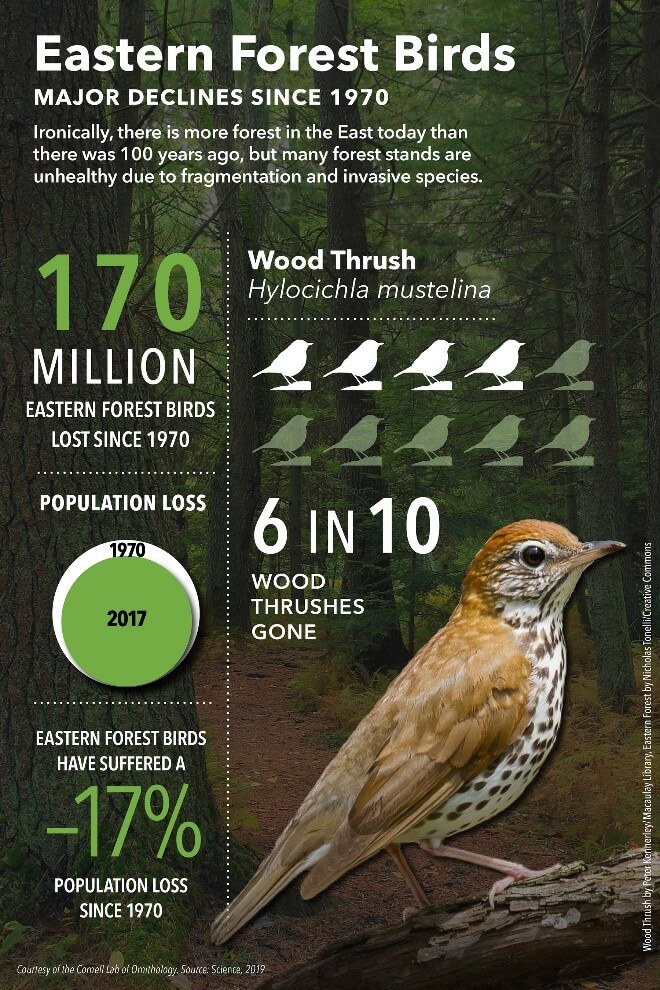

Eastern Forest Birds

Every year, millions of Wood Thrushes take to the skies, trading temperate for tropical forests. Many travel along the rolling ridges of the Appalachians, cross the Gulf of Mexico, and after brief sojourns to rest and refuel, alight in humid forests of Central America. This journey is not easy: There are countless threats along the way, including predators, especially cats.

Every year, millions of Wood Thrushes take to the skies, trading temperate for tropical forests. Many travel along the rolling ridges of the Appalachians, cross the Gulf of Mexico, and after brief sojourns to rest and refuel, alight in humid forests of Central America. This journey is not easy: There are countless threats along the way, including predators, especially cats.

Both feral and outdoor-roaming pet cats impact wildlife in a big way.

Our Cats Indoors Program educates the public and policy makers about the many benefits to birds, cats, and people when cats are maintained indoors or safely restrained outdoors. In addition to advocating for responsible pet ownership, we also oppose Trap, Neuter, Release (TNR) for feral cats because of the long-term, severe threats posed to wildlife by these cats.

We're leading a movement to overcome local and national challenges caused by roaming cats, bringing about change by conveying the most current scientific information, promoting science-based policies, and working with diverse stakeholders such as animal shelters, veterinarians, wildlife rehabilitators, and conservation biologists.

Jordan E. Rutter is ABC's Director of Public Relations.

Jordan E. Rutter is ABC's Director of Public Relations.