Edwin Way Teale was an American naturalist, photographer, author, and friend to Rachel Carson and Roger Tory Peterson. In 1947, he set out on a 17,000-mile road trip that led to the classic book, North with the Spring. He ultimately wrote three more books chronicling the seasons; the last, Wandering Through Winter, won the Pulitzer Prize.

Inspired by Teale, naturalist Bruce Beehler undertook 100-day cross-country road trip to once again celebrate one of the greatest wildlife events on earth: the annual migration of billions of American songbirds. On a journey from the Texas coast in early April to the to the wilderness of Ontario in July, Beehler recounts searching for species, exploring habitats, and meeting people who are working to save the birds and the awe-inspiring phenomenon that brings them north each spring.

The Golden-winged Warbler features prominently in Beehler's "North with the Spring" journey. On a fast track toward extinction, the Golden-winged Warbler's population has declined by more than 75 percent over the past 40 years, making it a top priority for conservation.

Beehler intersected with Golden-winged Warblesr at High Island, near Galveston, just as they arrived from points south—and tracked with them in both Wisconsin and Minnesota as they flew north to breed.

Dr. Beehler, an ornithologist, conservationist, and naturalist, is a Research Associate in the Division of Birds at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History. He has published 10 books and authored scores of technical and popular articles about nature. In 2007, Beehler was featured in a "60 Minutes" piece highlighting an expedition he led to the Foja Mountains in the interior of New Guinea, where scores of new species were discovered.

"North with the Spring" was proudly sponsored by

American Bird Conservancy and Georgia-Pacific.

|

Learn all about Bruce Beehler's "North With the Spring" journey in his blogs below:

Table of Contents:

26 March 2015, Blog #1 of my North with the Spring journey:

The winter has been awful in suburban Washington, DC. The first glimmers of spring—blooming crocuses and early morning song of American Robins and Mourning Doves—have revived hope for better things to come.

The song of American Robin is a welcome sign of spring. My journey will bring the season into focus: the sights, sounds, and most of all, the incredible journey of migratory birds. Photo by cpaulfell/Shutterstock

Last week, flocks of aggressive Red-winged Blackbirds appeared out of nowhere to take over the feeders in my back yard in Bethesda, Maryland. Their arrival reminds me that, indeed, spring is close upon us, and that I need to quicken my pace to prepare for my upcoming field adventure.

Chasing Songbirds

I'll be packing up my car this weekend and launching a hundred-day road trip. My journey is inspired by the renowned naturalist Edwin Way Teale, whose book, North with the Spring, told the story of his own East Coast adventure following spring from Florida up the Eastern Seaboard to northern New England.

Canada Warbler is one of many migratory birds I expect to spend time with on my journey, as we make our way to the boreal forest where many of these birds breed. Photo © Michael Stubblefield

I will track migrant songbirds from their landfall on the Gulf of Mexico, north through the Mississippi Valley, and into the Great North Woods of Ontario, where many of the birds settle down to breed in those raw boreal forests with the ever-so-long days of the summer solstice.

Along the way, I will camp out with the birds, mingle with birders, talk with research scientists, and participate in bird-banding work and other survey activities.

I will visit many of the most important stop-over and breeding sites in America's Heartland: postage-stamp-sized woodlots on High Island, Texas; bottomland forests in the Mississippi Delta; cypress swamps in northeastern Texas; mixed forests in Wisconsin; and boreal bogs in Minnesota.

I'll match my time in these wonderful bird hotspots with the peak arrival dates of migrant warblers—paying special attention to the Golden-winged Warbler, one of our most rapidly declining wood warblers—as well as vireos, thrushes, and flycatchers.

Tribute to Teale—and to My Mother

Why North with the Spring? This and other similar books by Teale were favored reading for my mother, an amateur naturalist, and these Teale nature books became a part of my DNA as a budding naturalist back in the 1960s.

![Bruce, Cary, Bill, Christmas 1957[2]](https://abcbirds.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/bruce-cary-bill-christmas-19572.jpg)

A younger version of myself (left) with my mother Cary and brother Bill in 1957. When I first hear a Cerulean Warbler this spring, I'll think of them. Photo courtesy of Bruce Beehler

So it is something of a tribute to my mother, who died a bit more than a year ago, to make this spring pilgrimage with the songbirds. I can recall her packing the beat-up family station wagon for a weekend at Rock Run Sanctuary on the Susquehanna River in Maryland. She, my brother, and I would spend those early summer days chasing butterflies and birding the dark green glens.

This coming spring, when I hear my first Cerulean Warbler giving its musical, buzzing and trilling song from a high oak in Missouri or Illinois I will stop and think of the first time my mother, brother Bill, and I heard that glorious song in a tall sycamore at Rock Run more than half a century ago.

So Our Grandchildren Can Wonder

I'll be visiting some of the most beautiful natural sites in the Mississippi Flyway at a time when they will be overflowing with the song of migrant birds. At the same time, I'll be capturing those sights and sounds for this blog.

If you're eager to journey with the songbirds—or to witness alligator snappers and canebrake rattlesnakes, hellbenders and black bears, wolves and caribou—please follow along!

A northern bog at sunrise, a sight I'll be lucky enough to enjoy on my travels with the birds. Photo by Bruce Beehler

In reporting what I see during this journey, I hope to tell the story of spring and spring migration and of the work so many people are doing to ensure that our grandchildren can wonder at the song of a Cerulean Warbler in a big old tract of majestic hardwoods that has been protected for us all—birds and humans alike.

I thank American Bird Conservancy, the sponsor of this adventure, nine close friends and supporters of my work—you know who you are—and Georgia-Pacific, which provided a generous grant that is making my pilgrimage possible.

29 March 2015, Blog #2 of my North with the Spring journey:

Rough-winged Swallow, one of the first migratory birds Bruce Beehler encountered as he headed toward Mississippi on his journey "North with the Spring." Photo by Greg Homel, Natural Elements Productions

Today's the day! I rise at 6:16 AM, have a quick breakfast, and my wife, Carol, and I race to jam everything into the car, and get the bike and kayak into racks on the roof. The air temperature at 7:40 AM when I depart is a wintery 29 degrees F. Not a cloud in the sky. Northwest cold front is blowing.

Packing the car was a careful, calculated affair – and sort of like a game of tetris. Photo by Bruce Beehler

The car – laden with camping equipment, a bike, and a kayak – is packed and ready to go. Photo courtesy Bruce Beehler

Eager for my North with the Spring adventure to begin, I race westward on interstate 66. Seeing the maroon outline of the Bull Run Mountains convinces me I am really on my way.

I turn southwestward onto interstate 81—down the valley of the Shenandoah—where Stonewall Jackson's troops kept the Yankees tied in knots more than 150 years ago. South of Staunton, Virginia, I can see snow atop the Blue Ridge.

Just south of Roanoke, Virginia, I see the first hint of softest green in the canopy in a protected bottomland. Also red maple buds are ready to burst here. Forsythia is blooming in the median strip.

My birdlist so far is mainly crows and vultures and grackles and feral pigeons. (But surely, more birds are forthcoming!) In Abington, Virginia, I see rich green hills dotted with sheep.

The long, lonely highway of a spring migrant of the human variety. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Tennessee Interlude: 60 Black Vultures

In east Tennessee I see a flock of 60 Black Vultures—the day's birding highlight. A small woodchuck along the highway's edge is my first living wild mammal of the trip. I will be keeping lists of birds and mammals throughout.

Imposing purple mountains in the distance to the east are the Smokies, I suspect. They are covered in snow. In a valley near Knoxville, the tulip trees are really popping their leaves. Down in a bottom several cottonwoods are budding electric yellow-green. Signs of spring!

I follow 81 to 40 to Knoxville; beyond Knoxville, in Loudon, Tennessee, I stop for the evening, having racked up 500 miles. I set up my tent beside the manager's house at the Express RV Park, no more than a quarter-mile from the highway (now interstate 65).

Nothing beats a camp stove for a hot meal on the road. Photo by Bruce Beehler

I dine in a wonderfully eclectic Mexican restaurant, filled to capacity with local families in their Sunday best, celebrating Palm Sunday. I feel underdressed, but much enjoy the tangy home-made guacamole and steak tacos.

Into the Deep South

30 March arrives with heavy rain at 4 AM. I sleep comfortably, though am woken periodically by the manager's heat pump that noisily shudders on every half-hour or so through the night.

Back on the road by 6 AM. This is a five-state travel day—three of those states being lifers for me. First Tennessee—passing through the hilly and river-girt Chattanooga, which leads me to the northwest corner of Georgia—foggy, mountainous, green, and like a painting! I pass an exit to an evocatively named place named Rising Fawn.

By 9 AM I am well into Alabama. There's mistletoe in the trees and hilly country in the northeast of the state. I see my first bald cypress just beyond Tuscaloosa—home of the Crimson Tide football dynasty. I pay my respects at Bryant-Denny Stadium, which rises like a sports-pyramid among the campus buildings.

Finding Spring in Mississippi

I cut southwest across the state to the Mississippi line, where I am greeted by planted magnolias along the highway—that's a first for me!

Entering Mississippi, where spring is beginning. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Now, poignantly, I am in (former) Ivorybill Woodpecker country of piney woods and swamps as I head toward Meridian, Mississippi. I see a thick understory of saw palmetto in the forest.

The yellow jessamine is in flower, and Rough-winged Swallows are in the air. I am in the Deep South now, and spring has arrived!

1 April 2015, Blog #3 of my North with the Spring journey:

Sadly, there are no Ivorybill Woodpeckers left in Ivorybill country, but there are plenty of Ivorybill cousins, like this Pileated. Photo by Orhan Cam/Shutterstock.

I arrived at the lovely Lake Bruin State Park the evening of 30 March, having driven 1,000 miles from Bethesda, Maryland in two days. The park is sandwiched between the main flow of the mighty Mississippi (a half-mile to the east) and an old oxbow lake to the west—Lake Bruin.

Lake Bruin: A Birder's Playground

The park, in rural northeastern Louisiana, is about 35 miles south-southeast of Vicksburg, Mississippi. This is home of the Tensas River, a place where Teddy Roosevelt came in 1907 to shoot a bear and ended up creating a public relations sensation: the “Teddy Bear.”

Even more important, it is the last wild patch of low country where the last good-sized population of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers lived and nested back in the early 1940s. I wanted to visit that hallowed ground—a place I had first read about as a youngster in Arthur Cleveland Bent's Life Histories of North American Woodpeckers.

Lake Bruin was a birder's playground. When I wasn't looking up at Red-headed Woodpeckers, I was marveling at the very vocal Barred Owls calling crazily before dark around the park's verges.

Loggerhead Shrikes sat on telephone wires just outside the park grounds. But I was here to get into the wilds.

Visiting the Last Ivory-billed Stronghold

The next morning I jumped in the car and headed out in search of the headquarters of the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge. You would think it easy to find such a thing, but this is rural country with lots of swamps and bending rivers and unmarked dirt roads. I had to drive back north up to Tallulah, then east to Quebec, then south….

I came across this displaying egret in a rookery at Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Bruce Beehler

In the end, it was worth the effort. The center sits at the edge of a bend of the Tensas River with mature bottomland forest all around. I met with Kelly Purkey and Shirley Whitney, two smart wildlife refuge staff who gave me all the details of the refuge's natural history.

The visitor center sits right on the edge of Greenlea Bend, which held a territory of an Ivorybill in 1940. It and virtually all of the remaining ancient forest of the famous “Singer Tract” was cut-over in the latter half of the 1940s, and the great birds disappeared with the last of the great trees.

If there is some good news here, it is that the federal government and state bought up more than 70,000 acres of the Tensas River drainage and have managed it for nature and wildlife. In addition, I was told there was a patch of old-growth forest in a spot accessible by kayak—McGill Bend. Of course, I had to try to find it!

Finding Wilderness on the Tensas River

The following morning I headed out early to find a put-in on the Fool River that leads into the Tensas at McGill Bend. This was wonderful oak and sweet gum forest with a smidgen of cypress. I kayaked for three hours, scouting out the wilderness.

I'm hearing the sounds of spring, including the songs of species like the Prothonotary Warbler. Photo by Jay Ondreicka/Shutterstock

Gators moved about nervously, unsure of my kayak. Mississippi Kites passed overhead. Prothonotary Warblers and Northern Parulas sang from the wet verges. Carolina Wrens were everywhere in song. And the cousin of the Ivorybill—the majestic Pileated Woodpecker—was here in abundance, drumming, calling, sailing across the slow river.

I saw not a single person on the Tensas, and I felt the wonder of place that was once America's last wilderness.

I will be headed back there to tramp the forest…

3 April 2015, Blog #4 of my North with the Spring journey:

Snowy Egret and Roseate Spoonbill, two beautiful species breeding in a rookery on High Island, Texas. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

My latest trip took me from the cotton fields and swamp country of Louisiana to the prairie and cattle region of southeastern Texas—all in about six hours.

I admit I was in a bit of a hurry … after all, meeting the birds on High Island was to be a highlight of my North with the Spring adventure!

High Island: Woodlots of Small Songbirds

My destination was a small salt dome island isolated from the prairie mainland of east Texas by a broad swath of spartina grass saltmarsh. The island is something of a southern beach resort, being right on the Gulf of Mexico. It also leads to the famous barrier island that is Bolivar Peninsula.

The Golden-winged Warbler is a species one could expect to see on High Island, although they arrive later in April. I'll make to make a return visit to see this one. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

High Island itself is famous among birders for its small patches of oak woods that act as songbird migrant "traps."

Laboring across the Gulf waters coming north in the spring, the small songbirds arrive on land after their perilous overwater flight and happily drop down into these small woodlots to feed, drink, rest, and regroup.

In doing so, the birds make themselves readily observable by the birders who wander the winding sylvan trails. It's a wonderful way to see these normally elusive birds up close.

The Woodland Reserves

There are several nice reserves on High Island, including Boy Scout Woods, Hooks Woods, Smith Oaks, Red Bay Sanctuary, and Eubanks Woods. Each offers important shelter to migrating birds on the way northward.

Great Crested Flycatcher was one of the migrants making use of the wooded reserves on High Island. Photo by Ralph Wright.

Owned and operated by Houston Audubon and the Texas Ornithological Society, these sanctuaries are the focus of an annual springtime pilgrimage by birders from all over North America, who come in hopes of seeing a songbird "fall-out" in the spring.

Black-and-white Warbler was one of several species we saw at High Island, along with Red-eyed Vireo and many Myrtle Warblers. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

In a fall-out, large numbers of birds arrive in the afternoon and are present in abundance the following morning, making the lives of birders very happy indeed.

The problem is that a fall-out is an uncommon phenomenon, based on special weather conditions and difficult to anticipate. In fact, we had hoped for one—hence my hurry to High Island—but we were disappointed.

That, of course, is the challenge of birding!

Smith Oaks Reserve's Amazing Rookery

If the migrant landbirds are sparse in the woodlots (as they were for me) one can travel to the heron rookery in the back of the Smith Oaks Reserve.

This is a guaranteed winner for birders and nature photographers, because there are hundreds of Great Egrets, Snowy Egrets, Roseate Spoonbills, and Neotropic Cormorants perched in shrubbery just across a narrow water gap that is guarded by alligators (thus keeping out pesky predators that might otherwise consume the eggs of these breeding waterbirds).

Great Egrets, Roseate Spoonbills, and Snowy Egrets were some of the birds I photographed at the Smith Oaks rookery: A true spring garden with living flowers. Photo by Aditi Desai.

The color and noise is mind-blowing and the displays by both the spoonbills and the egrets have to be seen to be believed. This is a crowded city of beautiful birdlife, right there to be enjoyed.

Onward to Bolivar Peninsula

But wait, there's more…. When things are slow on High Island, it is just a matter of driving a few miles down the coast along the Bolivar Peninsular to find mudflats crowded with scores of species of water birds—pelicans, herons, gulls, terns, godwits, avocets, curlews, plovers, oystercatchers, and more.

Terns, pelicans, skimmers, gulls … the coast was crowded with birds at Bolivar Flats. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Many of the birds are in large flocks, often at close range, especially when the tide is high and the birds are concentrated near the tide line. This site rivals that of the rookery but is ever-changing because of the tides and the seasons.

What a way to start a birding adventure, on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico!

5 April 2015, Blog #5 of my North with the Spring journey:

Scarlet Tanager was one of the species that quickly filled a tree with color on Monday morning, along with Myrtle Warbler, Black-and-White Warbler, and Red-eyed Vireo. The migration had started! Photo by Brian Lasenby/Shutterstock.

On Easter Sunday I was fortunate enough to celebrate a festive mid-day dinner outdoors at the Boy Scout Woods, on High Island, Texas.

The group of about 30 birders was celebrating the year's work of the many volunteers of the Houston Audubon Society, which operates this wonderful reserve visited by thousands every year from all over the country.

(They also work closely with American Bird Conservancy to conserve beach-nesting birds on the Texas coast.)

Houston Audubon is a leading conservation force in this area. Conservation Technician Kristen Vale had just banded Snowy Plovers on nearby East Beach—a joint effort with American Bird Conservancy's "Save Gulf Birds" program. Photo by Aditi Desai.

We were joined by the “paterfamilias” of bird tours, Victor Emanuel, and world-famous wildlife artist Robert Bateman and his family. It was wonderful to hear these two great personages recount evocative stories of Alaska and New Guinea and other exotic natural places around the world.

Myrtle Warblers were arriving in groups to make use of the reserve for resting and feeding. Photo by Elliotte Rusty Harold/Shutterstock.

The songbirds were quiet on Sunday but started to pick up on Monday, where a single tree at the reserve edge quickly produced three Scarlet Tanagers, five Myrtle Warblers, a Black-and-White Warbler, and a Red-eyed Vireo. The migration has started!

My Migration to Matagorda Bay

Late Monday morning I packed up my kit at the High Island RV Park and headed southwest down the Bolivar Peninsula. My destination: the 7,000-acre coastal prairie reserve owned and managed by the Nature Conservancy on Matagorda Bay.

The wildflowers in Texas are nothing short of spectacular. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Seven thousand acres is a lot of Texas coastal prairie—a habitat that is now in short supply (as with most natural prairies). It is flat, open, and spectacular, and it is filled with birds of many varieties.

Annually, this is the Christmas Bird Count site with the highest species total in the entire United States.

Spring Fever on Mad Island, Texas

Spring is the best time for birds at this Preserve. There are the last of the wintering birds hanging on, various local migrant birds arriving to breed locally, and the many neotropical migrants passing through on their way northward.

I was fortunate to spend time this past week with Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, which conducts a bird banding project here in a coastal thicket that looks out onto Matagorda Bay. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

The Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center conducts a bird banding project here in a coastal thicket that looks out onto Matagorda Bay, sheltered by the long sandy Matagorda Peninsula.

Bird-banding on the Front Line

This is the absolute front line in documenting each spring's initial northward movement of migrant songbirds coming across the Gulf of Mexico. There is no more southerly coastal banding project to detect avian migratory movements approaching our shores.

So far, the Mad Island Team has documented about 40 species of Neotropical songbird migrants dropping into the little patch of coastal scrub where the mist-nets are placed. The species include Indigo Bunting, Blue Grosbeak, and Hooded, Kentucky, and Swainson's Warblers.

The Team is still waiting for the “big push” and perhaps a first coastal fall-out of the season, when northerly winds and/or rain and fog knock down large numbers of birds, who head for the safety of coastal woodlands like the little scrub patch where this intrepid group is banding every day.

They have to be intrepid—facing strong winds, sun, swarming mosquitoes, coral snakes, and diamondback rattlesnakes. There are long days that start before dawn, which sometimes bring the excitement of new avian arrivals—or instead the boredom of empty nets.

Ducks and More on Mad Island

Since I got to Mad Island, I have also visited three private wetlands not far from here, with waterfowl and wetland experts from Ducks Unlimited (DU).

Ducks are not the only species to benefit from Ducks Unlimited's conservation work. The Yellow-crowned Night-heron is another. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

DU is one of the largest private conservation organizations in the United States. By conserving high-quality wetland habitat for wintering ducks, these projects also create important habitat for migratory shorebirds, ibis, herons, and more.

The private wetlands I visited were working properties with agriculture or cattle (or crawfish ponds in one instance). Flocks of Blue-winged Teal were in abundance on the ponds and White and Glossy Ibis, White Pelicans, Tricolored Herons, and much more was there for us to admire.

My "North with the Spring"transport, ready for the next stop in southern Louisiana. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Next stop, Southern Louisiana!

11 April 2005, Blog #6 of my North with the Spring journey:

Wilson's Plover is a beach nesting bird found on the Bolivar Peninsula. Houston Audubon in partnership with ABC is working to conserve these and other beach nesting birds. Photo by Chuck Tague.

Although I ventured down to the Gulf Coast to welcome the neotropical migrant songbirds, I have not been ignoring the other wonders of this bird-rich realm including Black Skimmers, Sandwich Terns, and many other species.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j7h4MK0kAfM&w=560&h=315

Bolivar Peninsula – A Bird-rich Realm

I recently visited with American Bird Conservancy's Kacy Ray on the beaches of the Bolivar Peninsula in Texas, to see the birds she is working on and to better understand the great bird conservation work being done on the beaches of the Gulf.

I had learned of Kacy's work while working on Gulf issues for the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, so I was excited to meet her during high season for beach nesting birds.

I met with Kacy Ray at Bolivar Flats. ABC has worked with Houston Audubon for the past four years to implement important conservation measures for these vulnerable birds. Photo courtesy of Bruce Beehler.

Partnerships to Benefit Birds

ABC partners with local organizations and field teams in states across the Gulf Coast to address threats to Wilson's Plover, Snowy Plover, Black Skimmer, and Least Tern.

These lovely birds make their nests right in the sand above the high tide line and thus are vulnerable to beach-goers, unleashed dogs, motorized vehicles on the beach, and nest predators such as raccoons, coyotes, and gulls.

Kristen Vale and Stephanie Bilodeau, ABC-Houston Audubon Shorebird Technicians, and Peter Deichmann of Houston Audubon weigh, measure and band Snowy Plovers on East Beach in an effort to monitor and conserve the declining populations of these species. Photos by Aditi Desai.

Fostering Bird Stewardship

Human disturbance can be remedied with a few key actions like fencing breeding sites, putting up educational signage, and training local volunteer bird stewards to look out for nesting areas during the breeding period.

Bird stewards spend busy weekends and holidays educating the public about beach-nesting birds and steering them clear of nesting areas.

Fencing off nesting sites and placing signs around the area helps increase awareness to protect these diminutive birds from beach-goers. Photo by Kacy Ray.

Seeing Plovers Decades Later

For birders such as myself, seeing a Wilson's Plover or a Snowy Plover provides a real charge. These species are common now only in a few places like Bolivar Peninsula and the Gulf Coast of Florida, where there is an abundance of habitat.

Nesting in open, unprotected areas, beach nesting birds like Snowy Plovers face many challenges in protecting their eggs and young. Photo by Kacy Ray.

Admiration from a Distance

Beach nesting birds have been in decline for several decades, but with the proper interventions, the most common types of disturbance can be reduced in critical locations, giving the populations a chance to rebound.

Seeing these plovers gives one a special feeling, knowing how infrequently we ever get a chance to spend time with them.

Thanks to the hard work of people like Kacy, Kristen, Stephanie, and the many partner organizations they work with, these birds will be around for the next generation of birders to admire from a respectful distance.

The day I spent out on the Bolivar Peninsula with Kacy, Stephanie, and Kristen was the first time I had seen Wilson's Plovers and Snowy Plovers for several decades. Photo courtesy of Bruce Beehler.

12 April 2015, Blog #7 of my North with the Spring journey:

The woods were filled with Summer Tanagers. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

A Stunning Coastal Wetland

A few days back, I drove 300 miles from Mad Island, Texas, up around the curve of the Gulf Coast to Grand Chenier, Louisiana—site of Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge, a stunning coastal wetland.

My host was refuge ornithologist Samantha Collins, who graciously made the resources of the refuge available for my visit.

The refuge oversees use of the nearby private Nunez Woods, which acts as a critical stop-over habitat for migratory songbirds arriving from their perilous journey north across the Gulf of Mexico.

Nunez Woods is a chenier oak woodland about a mile north of the Gulf. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Conserving the Phenomena of Migration

I met with the banding team from Professor Frank Moore's lab at the University of Southern Mississippi. Banding birds can help us better understand migration and inform conservation measures to protect birds from such threats as habitat loss.

Keegan Tranquillo, Shawn Sullivan, and Lauren Granger manage 30 mist-nets strategically set in the interior of the chenier woodland to band and monitor songbird migrants. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

A Spectacle of Colorful Birds

I arrived just as things were starting to heat up. Moore's team trapped more than 120 birds in the morning hours, before heavy rains closed the operation.

We were witnessing the start of the high season for songbird migration. I observed more than 40 species in a spectacle of songs and color as birds moved around the woods.

Unstable weather forced the birds down into our little chenier woodland. If the weather had been fair with southerly winds, many of these birds probably would have continued flying north. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Songbirds Traveling North

Hooded and Kentucky Warblers joined small feeding flocks with Wood and Swainson's Thrushes. A single adult male Cerulean Warbler spent several hours in a patch of oaks near the woodland edge. And the nets produced another half-dozen species of warblers, including the hard-to-see Worm-eating Warbler.

The team banded this Swainson's Warbler during a morning filled with many migratory bird species. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Trees Bearing Blue Fruit

The most remarkable phenomenon of all was the blue-and-brown flock of Indigo Buntings and Blue Grosbeaks.

The shimmering blue of the male buntings and the richer, darker blue of the grosbeaks created a remarkable sight: like blue fruit scattered through the branches. This was the first time I had seen these two iconic blue birds associating with each other.

There were more than 50 Indigo Buntings and at least a dozen Blue Grosbeaks. I followed this colorful flock for almost an hour. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Yellow-billed Cuckoos, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Acadian Flycatchers, and scores of White-eyed Vireos made the woods vibrate with birdlife. In spring, each day brings new surprises.

The Rose-breasted Grosbeak was just one of many delights I saw at Nunez Woods. Photo by Jane Gulbrand/Shutterstock.

12 April 2015, Blog #8 of my North with the Spring journey:

Fulvous Whistling-Ducks flush in Louisiana. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

From the south coast of Louisiana, I drove north to West Feliciana Parish to visit forests managed by Georgia-Pacific Corporation. In this region, I could combine history with ornithology: visiting historic Civil War battlements from the 1863 Siege of Port Hudson and the site where John James Audubon painted 32 of his Birds of America plates.

I met with two Georgia-Pacific representatives to tour the company's forest reserve. The southern sector of their site is now lush oak forest on the east bank of the Mississippi River: prime habitat for migrant songbirds.

The day we toured the woodland, the faunal highlight, though, was a pair of very large and brightly patterned Eastern Box Turtles that hung out in the trail leading to the Confederate earthworks.

An Eastern Box Turtle at a forest reserve in Port Hudson, La. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Singing for the Ghosts

Summer Tanagers and Hooded Warblers were noisy in spite of the thick fog. Of course, resident Carolina Wrens and Northern Cardinals also were common here, and small White-throated Sparrow flocks worked the edges of the dark thickets.

It was cool and damp and even though some birds were singing, one could feel the ghosts of fierce conflict that took place here.

Despite the fog, Hooded Warblers were noisy. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Audubon's Inspiration

The following morning, I bicycled over to Oakley Plantation, just south of St. Francisville. The drive to the 1799 plantation house is hemmed in by giant loblolly pines and oaks—misty and majestic.

The woods were filled with singing birds: Hooded, Kentucky, and Pine Warblers; Summer Tanagers, Great Crested Flycatchers, and the flutelike notes of the Wood Thrush. Red-headed and Pileated Woodpeckers called out from the mists.

Audubon painted many of his famous Birds of America plates, including the Swallow-tailed Kite and the Pine Warbler, at Oakley Plantation in St. Francisville, La. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Along the Pearl River

My next stop was in central Mississippi, at more than 2,000 woodland and wetland acres that Georgia-Pacific manages under the Wildlife Habitat Council's Wildlife at Work program.

Here I watched Anhingas soaring over the wetlands, a rookery of Great Egrets, and abundant Indigo Buntings. Alligators patrolled some of the freshwater ponds. To the east of the property flowed the Pearl River, whose watershed harbored Ivory-billed Woodpeckers into the 20th century. I have a soft spot for these Ivory-billed sites!

Anhingas, with their black and white "piano key" feathers, are always a joy to see. Photo by Jill Nightingale/Shutterstock.

20 April 2015, Blog #9 of my North with the Spring journey:

A Milk Snake in Caddo Lake, Tex., where reptiles and amphibians are abundant. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Caddo Lake, in northeast Texas, is famous for its paddlefish and stands of bald cypress. I went there to check out the local protected areas: a state park, state wildlife management area, and a national wildlife refuge. I was happily surprised to learn that a field herpetology class from West Texas A&M University was also visiting.

Students from West Texas A&M University encountered this American Green Tree Frog while doing a survey of reptiles and amphibians at Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

In the Field

The field group was led by Richard Kazmaier, and included seven smart, energetic students. This was the fourth year students had conducted herp surveys in the Caddo Lake National Wildlife Refuge, an area remarkably rich in frogs, snakes, turtles, and lizards. With the students' help, I was able to get close looks at quite a few.

I saw a species of hog-nosed snake. It was a real treat! Photo by Bruce Beehler.

I had hoped to see an Alligator Snapping Turtle. In 2014, Kazmaier's group netted a hundred-pounder. This year, none. That was the sole disappointment of my visit. But there was another creature I wanted to spend time with — the Water Moccasin — and in that I was not disappointed. With the students' help, I photographed a mature individual.

This adult Water Moccasin was not too aggressive. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Haven for Snakes, Frogs, and Turtles

Among the other special creatures I saw: Milk Snake, Rough Green Snake, Diamond-backed Water Snake, Rough Earth Snake, Green Tree Frog, Gray Tree Frog, Spring Peeper, Red-eared Slider Turtle, Stinkpot Turtle, and Mississippi Green Water Snake.

A juvenile Red-eared Slider Turtle in Caddo Lake, Texas. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Wonders of Nature

Birders tend to spend little time thinking about the herpetofauna—reptiles and amphibians—of a particular region. But these animals are an amazing part of Nature's creation.

Rough Green Snakes, like this one in Texas, search for insects in vegetation. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

In this part of the world, though, herps do not fare well. Turtles get hit by cars when crossing the road, and every snake that enters someone's backyard meets a hasty end. People do not give herps a break, and that's a shame. They are wonders of nature!

18 April 2015, Blog #10 of my North with the Spring journey:

Many species of songbirds including Yellow-throated Warbler visit the Caddo Lake area. Photo by Paul Reeves Photography/Shutterstock.

Caddo Lake is a dammed section of Big Bayou Creek, which flows into the Red River and is part of the Mississippi drainage basin. I visited because I was entranced by the thought of kayaking through the cypress forests – festooned with hanging gray tangles of Spanish moss – that fringe the lake. And the backwater passages through these drowned forests are otherworldly.

Cypress trees and water so muddy it looks black give Texas's Caddo Lake an otherworldly feel. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

The Caddo Lake area is rich with protected lands and waters, and it is a wonderful place for an ornithologist to spend time. The uplands are either piney woods or hardwood forests, and the bottoms are cypress. Each habitat supports its own suite of breeding neotropical migrant songbirds.

Caddo Lake offers a variety of habitats that draw migratory songbirds like this Yellow-breasted Chat. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

A Forest Teeming with Birds

One afternoon I hiked through a lovely patch of old-growth oak forest with Vanessa Nease, a research biologist for the Caddo Lake Wildlife Management Area. Ames Spring Basin is her favorite patch of hardwood glen forest in the area. Protected in several deep ravines leading down to the lake, it featured towering oaks, ashes, sweet gum, and hickory. The understory included wildflowers, ferns, and canebrake.

Vanessa Nease, a research biologist, in the old-growth forest known as Ames Spring Basin. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Forest reserves like these support breeding populations of a wide range of neotropical migrant songbirds. We saw Northern Parula, Red-eyed Vireo, Black-and-white Warbler, and Summer Tanager in our afternoon hike. Setting aside this tract of old growth forest makes a huge difference for our migrants, and we should strive to save every last stand of old growth. These are places where the more sensitive species can nest without being located by the Brown-headed Cowbirds—wily and persistent nest parasites that lay their eggs in the nests of warblers and vireos and thrushes.

Watery Wonderland

The next day I paddled my kayak through Carter's Shute of the Caddo Lake WMA, which follows a marked trail through the stands of cypress. I got there before sunrise as mist was spreading across the still and black waters. I eased my kayak into the water and entered a wonderland.

As the sun rose, birds started singing—first Northern Cardinal and Carolina Wren, and then Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Prothonotary Warbler, Northern Parula, and Yellow-throated Warbler. Great Egrets foraged all around me. An Anhinga soared overhead. A Red-shouldered Hawk cried out in the distance. Then a Pileated Woodpecker drummed on a distant hollow trunk.

A symphony for the eyes and ears as a diverse array of bird species such as this Blue-gray Gnatcatcher gather in waters of Caddo Lake WMA. Photo by Greg Homel.

I explored a side channel on the way back and there was a Barred Owl perched low on the cypress stub in the water. I quietly drifted closer as it mutely watched me in my kayak. I snapped pictures until I was too close for my long lens. Magic!

Barred Owls are among the many creatures that live among the stands of cypress. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

I saw not another soul on my two-hour circuit. It was utterly peaceful. This is the true and lasting value of wilderness. We can never let down our guard on behalf of these special places. They are invaluable resources that make living worthwhile, and help us recharge our souls.

20 April 2015, Blog #11 of my North with the Spring journey:

Northern Parula is one of the many neotropical migratory bird species you can spot at Caddo Lake State Park. Photo by Greg Lavaty.

On Sunday, April 19, I got up at 5:30 a.m. at Caddo Lake State Park to head to Nacogdoches, Tex., where I had plans to meet up with a group of ornithologists. From there, Texas's state ornithologist would take us birding south of town. Caddo Lake where I was staying is a great place to spot all types of birds including migratory species.

An Unexpected Twist

A half-hour into my trip, the car's engine oil light registered “High.” I turned around and slowly brought the car into a Chevron station. A quick look under the hood showed the engine had no oil and no water. (Why? We will never know). I filled up both. An employee strolled out of the Chevron store and started naming things that might be wrong with my car—people in country towns in Texas know cars like I know migrant wood warblers—and called a local mechanic. He gave the car the once-over, flushed the radiator system, and I was good to go…or so I thought.

By this point I had missed the bird walk. I headed back to Caddo Lake. Four miles in, the engine stopped, and I drifted the dead beast onto the grass beside the road. I called the Chevron station, and a wrecker came to pick up the car and deliver it to a Nissan dealership 25 miles away in Longview.

Due to car troubles, I missed the birding trip near Nacogdoches. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Everything is closed on Sundays in Texas, even the car dealers and rental car companies. But the driver found an open Avis desk at the tiny regional airport in neighboring Kilgore. They had a single car available to rent: a Ford Explorer, which could hold all my stuff. By late afternoon, I was back at my campsite in Caddo Lake, wondering what happened to my car.

Re-reading North with the Spring and books by other naturalists back at camp is an absolute pleasure. Photo by Aditi Desai.

The Replacement

Tuesday morning, I learned the engine was shot. I needed a replacement car. At the Nissan dealership, as an employee prepared to show me a new Nissan Xterra, I noticed a used one in the parking lot, with an elderly gentleman locking its door. I asked if that was his car. It was his wife's, he answered, but she would be trading it in for a new sedan within the hour.

Luckily, I was able to purchase a new car to continue on my journey. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

By early evening, I was on the road in my 2007 Xterra, with the North with the Spring insignia on the door panels. Next stop: High Island, Tex. Hopefully, this time I'll get even more opportunities to see neotropical migratory species coming in from across the Gulf.

27 April 2015, Blog #12 of my North with the Spring journey:

Seeing the Golden-winged Warbler was particularly special because it is the emblem for my journey. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

The real-time arrival of songbird migrants coming north across the Gulf was something I very much wanted to see during this journey. So after my travels to Mississippi, Louisiana, and Caddo Lake, I returned to High Island. And I got my chance to see the songbirds – including the Golden-winged Warbler – fill a tiny patch of woods along the Texas coast.

Flocks of Indigo Buntings invaded High Island after crossing the Gulf on their northern migration. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

These little woodlots are precious to migrating birds, who have flown more than 600 miles across the Gulf of Mexico: hummingbirds, warblers, vireos, catbirds, orioles, grosbeaks, thrushes, and more.

Haven for Migrants

Boy Scout Woods, operated by the Houston Audubon Society on High Island, provided a first encounter: dozens of Tennessee Warblers flocking to feed on the nectar of red bottlebrush shrubs on the roadside. These canopy-dwelling forest warblers were at eye level and only a few steps away from me. With them in the flowers were Indigo Buntings and orioles.

A Baltimore Oriole on High Island. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

The parking lot at Smith Oaks, another Houston Audubon operation, featured mulberry trees that filled with groups of Rose-breasted Grosbeaks and Summer Tanagers, feeding lustily while my camera clicked over and over. Male grosbeaks, in all their finery, jostled for prime feeding perches, while birders goggled in amazement. In one afternoon, I must have seen more than 75 Rose-breasted Grosbeaks and more than 50 Summer Tanagers.

To the amazement of birders, dozens of Rose-breasted Grosbeaks jostled in the mulberry trees. Video by Don DesJardin.

Flood of Songbirds

Sabine Woods, a conservation property of the Texas Ornithological Society about 20 miles east of High Island, provided the first major songbird invasion. Normally, the migrants come in the afternoon. We arrived before the birds, and by 4 PM they were flooding into the shade of the live oaks: small groups of Painted Buntings, flocks of Indigo Buntings, dozens of Northern Waterthrushes foraging in the pools of water, scores of Swainson's Thrushes hiding in the shady understory, and too many Ovenbirds to count.

Shaded by live oaks, a Painted Bunting arrives at Sabine Woods. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Two male Golden-winged Warblers arrived, plus a singleton female. By a small, shaded wetland, a Cerulean Warbler foraged close to the ground, its bright blue back gleaming in an afternoon beam of sunlight that penetrated the canopy. Everywhere were birds: Bay-breasted Warbler, Philadelphia Vireo, Black-throated Green Warbler, and more.

Bay-breasted Warblers were among the many species of migratory songbirds that flocked to Sabine Woods after crossing the Gulf. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

The wisdom of the local bird organizations to purchase and manage these precious places is profound. Conservation of these small woodlots—islands of safe habitat surrounded by marshland and rice fields—are first-stop lifesavers to famished and exhausted migrant birds.

Black-throated Green Warbler, Cerulean Warbler, Philadelphia Vireo, and Tennessee Warbler were some of the many species at High Island. Photos by Bruce Beehler.

May 5, 2015 Blog #13 of my North with the Spring journey:

A male Prothonotary Warbler in a swamp forest at Louisiana's Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

After my second visit to Texas's High Island and the Bolivar Peninsula, I headed back to Louisiana to the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge. This is where Cornell's James Tanner studied a population of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the late 1930s, and I wanted to visit the McGill Bend of the Tensas (pronounced “Ten-saw”), a 7,000-acre tract of mature bottomland forest. This time I would be there during peak migration.

Accompanied by the refuge forester, we made our way there on an all-terrain vehicle—quite an experience for me, plowing through deep mud and thigh-deep blackwater into what is probably one of the wildest forest patches in the the South. Although dominated by oaks — overcup, cherrybark, water, nuttall, and willow — the forest also has many other types of trees, including American and cedarbark elm; sweet gum; green ash; sassafras; hackberry; honey and black locust; and persimmon.

I explored McGill Bend Forest with Nathan Renick, forester for Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge in Louisiana. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Birdsong came from every direction—Pileated Woodpecker; Prothonotary, Swainson, and Kentucky Warbler; Summer Tanager; Great Crested Flycatcher; Carolina Wren; Tufted Titmouse; and many others.

Back in the Bottoms

Mature bottomland forest has been significantly reduced in the lower Mississippi over the past 150 years. The last of the virgin stands were cut in the late 1930s. Good bottomland forest is probably less than 1 percent of its original extent—having been replaced by rows of milo, rice, cotton, and other crops. To spend a whole morning in this huge tract of big forest took me back in time.

Pine Capital of Arkansas

About two hours north of Tensas lies Crossett, Arkansas. I visited Crossett to do some environmental education work in partnership with my corporate sponsor, Georgia-Pacific. I saw flooded bottoms with cypress, upland stands of pine, and everything in between — including a loblolly pine 62 inches in diameter and more than 130 feet tall. There are not many trees like that left in Arkansas!

While touring the diverse forest ecosystems around Crossett, Ark., with wildlife biologist Bobby Maddrey and forester Don Sisson, both of Georgia-Pacific, we saw a giant loblolly pine. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Much of the landscape in Crossett is planted pine monoculture to feed the Georgia-Pacific mill that makes paper products. It's a very distinct landscape from what I encountered at Tensas.

Crossett's pine monoculture was very different from the bottomland forest I saw in the Tensas. Row crops now line the prime bottomland that once had forest with Ivory-billed Woodpeckers. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

Little Woodpecker of the Pines

Just west of Crossett, where the Saline and Ouachita Rivers pass through the landscape, the bottoms are flooded in spring. High waters inundated part of my campground and many of the roads of my next destination, Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge.

I came to spend time with a colony of Red-cockaded Woodpeckers. The woodpeckers are scattered through the old pine savannas of the refuge, which manages its pine stands for the birds through periodic burns of the understory to keep the forest open.

The Red-cockaded Woodpecker, pictured here in Arkansas's Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge, depends on open pine forest. Photo by Bruce Beehler.

This sort of habitat management is common for a wide range of rare species, including the little Red-cockaded, a habitat specialist listed as near-threatened. But there is hope: Thanks to fire management across the woodpecker's range, its prospects are brightening.

May 11, 2015 Blog #14 of my North with the Spring journey:

Forty acres of old-growth forest in Arkansas' Delta National Forest are home to giant trees like this sweetgum. Photo by Bruce Beehler

After leaving Crossett, Ark., I headed southeast to Mississippi. There, a resident forester at Delta National Forest guided me on a backwoods road to the Green Ash-Overcup Oak-Sweetgum Research Natural Areas. Here I found 40 acres of old-growth forest: Magnificent sweetgum trees were scattered among giant oaks, ash, and a dozen other Delta National Forest species. Many topped 120 feet in height; all were nestled within some 60,000 acres of forest.

A Haven for Migrants

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers almost certainly would have visited some of these big trees when they were only 150 years old. Today, these giants are more than 300 years old and shade a beautiful bottomland forest. On my visit, the trees hosted many calling Pileated Woodpeckers, as well as vocalizing Kentucky Warblers, Acadian Flycatchers, Prothonotary Warblers, and more. Mississippi Kites soared gracefully in pairs and triplets over openings in the canopy.

The gravel forest road that cut straight through the large expanse of forest was wonderful for butterflies and birds and other wildlife. Many Indigo Buntings moved along the edge of the road, and were especially abundant in places where the forest bordered the scrubby edges of fields. These birds were migrants headed up the Mississippi in droves.

Kentucky Warblers called from towering 300-year-old trees in Arkansas's Delta National Forest. Photo by Bruce Beehler

A Flooded Forest

After a night in Delta, I headed northwest Arkansas' White River National Wildlife Refuge. Walking along a bottomland trail that drops off the bluff and passes by the banks of the White River, I found foraging Northern Waterthrushes and singing Tennessee Warblers. And once more, I encountered small flocks of Indigo Buntings — a species that is turning out to be a featured migrant bird of the trip. Much of the area was flooded, including part of this bottomland trail.

The giant of the forest was an immense cherrybark oak with a diameter of more than five feet. In the late morning, I put my kayak in a flooded forest north of the main road. Prothonotary Warblers entertained me to no end: These were males on territory, and they were noisy and aggressive — as well as gorgeous.

Indigo Buntings, heading up the Mississippi in droves, have been a signature species on my journey. Photo by John L. Absher/Shutterstock

A Famous Woodpecker

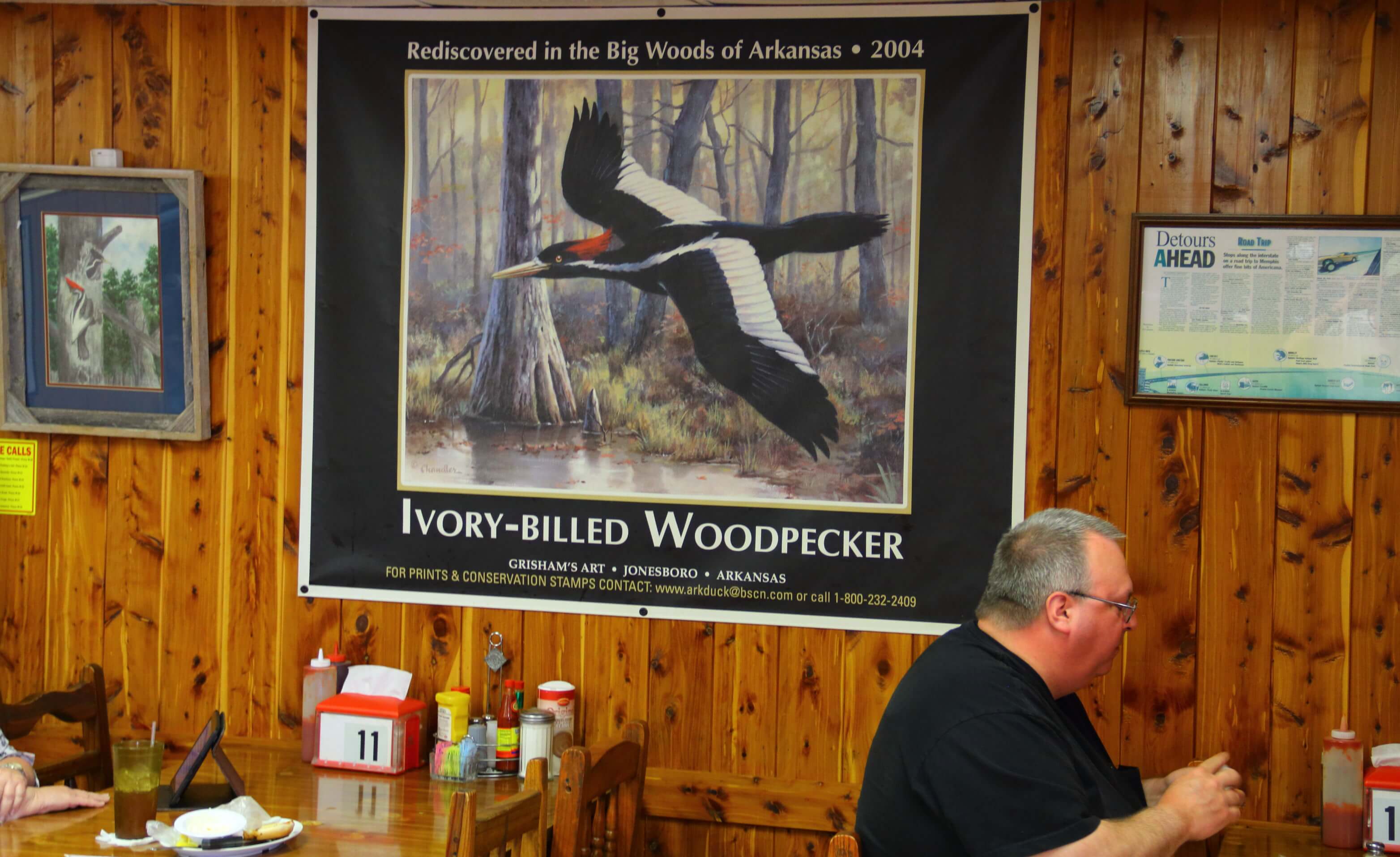

Because of my obvious fascination with the Ivorybill, I felt compelled to visit Brinkley, Ark., and the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge. There, I paddled the Bayou de View, where the famous 2004 sighting of the Ivorybill took place — an event that created a huge flurry of interest in this part of the world. Brinkley loved the publicity and interest the Ivorybill sightings generated; even today, some local establishments still highlight the Ivorybill in a big way.

A 2004 sighting of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the Cache River National Wildlife Refuge was big news in nearby Brinkley, Ark., where the bird's likeness features prominently in local establishments like Gene's Restaurant. Photo by Bruce Beehler

These tracts of bottomland hardwood forest are now exceptional features in the landscape. Row-crop agriculture now dominates the Mississippi Delta. Agricultural policy over the decades has led to the clearance of vast expanses of these wet forests, as farmers expanded into places not meant for this type of intensive production.

Today, some of these cleared areas have been bought back from farmers, and millions of dollars are being spent to bring back the forests to these cleared areas. I saw large-scale re-plantings at a number of national wildlife refuges. I am only sorry they were cleared in the first place.

Bottomland forests of the Mississippi Delta – once Ivorybill country – were cleared to create land more suitable to farming. Today, an effort is under way to bring back the forests. Photo by Bruce Beehler

May 12, 2015 Blog #15 of my North with the Spring journey:

Crossing the Mighty Mississippi. Photo by Bruce Beehler

After a long day of driving from Arkansas, I negotiated Memphis's evening rush-hour traffic and arrived at the little-known Meeman-Shelby Forest State Park. Located in Millington, Tenn., about 15 miles north of Memphis on the east bank of the Mississippi, the park is an unexpected sylvan oasis. It boasts 12,500 acres of old-growth hardwood upland forest as well as an impressive strip of bottomland — with a large stand of giant cottonwoods — right on the Big River.

Fabulous, Buggy Forest

This has to be one of the few places in the United States where one can drive through a closed canopy old-growth forest for miles and miles. Home to a number of champion trees, the park is also a stunning stopover for migratory birds. At this time, the park was filled with thrushes: resident Wood Thrushes as well as Swainson's and Gray-cheeked Thrushes passing through. They were everywhere. Given how few thrushes I see in the Washington, D.C. area in spring, this was a nice surprise.

Resident Wood Thrushes filled Tennessee's Meeman-Shelby Forest State Park on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Meeman-Shelby Forest had another notable feature: biting insects. This site, among many stout competitors, had the most ferocious biting insects of the trip so far. They were active noon and night — mosquitoes in the mornings and evenings, and black flies when the sun was high. Migrant birds seemed to love the horde. Large numbers of Tennessee Warblers sang in the forest, along with Hooded and Kentucky Warblers and many others.

Moving Fast

After two nights at Meeman-Shelby, I paid a quick visit to Chickasaw National Wildlife Refuge and then continued on to Reelfoot Lake, which hosts a state park and a national wildlife refuge. Reelfoot Lake features stands of cypress in lake water, a theme I have encountered in quite a few bottomland sites on this journey.

The surrounding agricultural lands were flat and overworked, though, with little in the way of natural habitat along the fringes. Too much agriculture today is industrial and wall-to-wall, allowing little marginal habitat in which nature can thrive.

Twin Lakes and Lovely Hills

What a change it was to visit Land Between the Lakes National Recreational Area. I left the Delta and entered hilly, forested uplands nestled between two sinuous lakes formed by the damming of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers.

I camped in an open oak forest overlooking Kentucky's Energy Lake, with a marvelous sunset my single night there. As dusk settled, I could have been in the middle of the Adirondacks, except the area was happily bug-free.

These Purple Martins were among the many birds I saw at Land Between the Lakes National Recreational Area in Kentucky. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Warbling Vireos, Scarlet Tanagers, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Red-eyed Vireos, and Great Crested Flycatchers sang in the canopy that evening, providing a pleasing day's-end chorus for an exhausted ornithologist. The next morning, during a long bike ride through the woods, I encountered 10 Tennessee Warblers, four Kentucky Warblers, and two Northern Parulas. Among the singletons I saw were Hooded, Black-and-white, Palm, and Myrtle Warblers. Refreshed by the brief stay between the lakes, by noon I was on my way to Missouri.

During a long bike ride around Land Between the Lakes, I saw this Black-and-white Warbler. Photo by Bruce Beehler

May 16, 2015 Blog #16 of my North with the Spring journey:

A Red-Headed Woodpecker in southern Missouri. Photo by Bruce Beehler

From Land Between the Lakes, in western Kentucky, I headed to Missouri, crossing the Mississippi once again. My destination was Mingo National Wildlife Refuge, where the eastern edge of the Missouri Ozarks meets the northern extension of the Delta—a perfect place for wildlife, especially migratory birds. Mingo featured all the goodies: expansive marshy wetlands, grasslands, cypress swamp, oak bottoms, and hilly and rocky uplands.

Early in the morning, I met up with Larry Heggemann of American Bird Conservancy, an expert on Missouri wildlife. As we stood birding in the parking lot of Mingo's visitor center, a car drove up with Mark Robbins and John Bollin, who were doing a four-day bird survey of the state. Mark is senior author of The Birds of Missouri. I first met Mark more than three decades ago, so it was great to have this surprise encounter.

I quickly spotted this Prairie Warbler at Cane Ridge, in southern Missouri. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Larry and I tagged along with these two for the early morning. Mark has a phenomenal ear and knows songs, calls, and chip notes. Birding with Mark was a rude reminder of how many warbler songs I now have a hard time hearing—a product of age and youthful decades of loud music.

With a lot of help from Mark, we saw more than a dozen migrant warblers and lots of thrushes and vireos to boot.

Shorebird Bonanza

Adjacent to Mingo is Duck Creek State Conservation Area, where Larry worked for many years as a wildlife officer. He gave me the cook's tour. We focused on the wetlands and saw many shorebirds: Spotted, Solitary, Pectoral, and Least Sandpiper; Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs; dowitchers; and a single Black-necked Stilt. Waterfowl were abundant; Wood Ducks, in particular, were everywhere.

I spotted a Black-necked Stilt in the wetlands at Duck Creek State Conservation Area in Missouri. Photo by Dan Lebbin

Trail of Tears State Park

From Mingo I shifted my base to Trail of Tears State Park, 5,000 acres of hilly upland oak woods on a bluff overlooking the great Mississippi. Across the river were the rolling, forested hills of Illinois. The park's stunning location, several hundred feet above the river, is itself worth the price of admission. What a view!

Trail of Tears State Park has a sobering history, though. It marks the spot where groups of Cherokee Indians, uprooted by government mandate in the late 1830s, crossed the Mississippi on the way to a reservation in Oklahoma. What a beautiful place to memorialize such a terrible story.

Trail of Tears State Park featured Mississippi Kite, above, as well as Wood Thrush, Kentucky Warbler, and Tennessee Warbler. Photo by Greg Homel, Natural Elements Productions

Once Forest, Now Savanna

The Cane Ridge oak glades, near Poplar Bluff, Mo., is an area that forestry management has opened up into something of a savanna. Fire and selective clearing has allowed grassy understory to attract birds that live in early successional forests. Closed-canopy oak woods now dominate this protected landscape, shutting out the open-country birds, so the oak glades provides important habitat.

At Cane Ridge, forestry management has created grassy understory that attracts birds like this Yellow-breasted Chat. Photo by Bruce Beehler

The management has clearly worked, and needs to be done in more places. At Cane Ridge, it has had the desired effect on the bird fauna: I quickly located Red-headed Woodpecker, Prairie Warbler, and Yellow-breasted Chat, and a bonus bird was an Olive-sided Flycatcher, stopping over on its way to Canada. I missed seeing Blue-winged Warbler, a bird Mark had gotten the previous day.

This Olive-sided Flycatcher stopped in southern Missouri on its way to Canada. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Mosquitoes and Migrants

My last morning in Missouri I spent at Big Oak Tree State Park, famous for its champion trees and also an excellent warbler trap. Rain interfered, but there were good numbers both of mosquitoes and migrant songbirds. Golden-winged Warbler was the bird of the day. Next stop, Illinois!

May 20, 2015 Blog #17 of my North with the Spring journey:

Black-throated Blue Warbler was among the 54 species I saw at a "migrant trap" in central St. Louis. Photo by Scott Streit

Arriving in southern Illinois, I came to Trail of Tears State Forest. Foresters here are working hard to manage this beautiful mature oak forest for the long-term, which means planning for a forest succession that maintains a dominant oak overstory beloved both by hunters and birders.

I saw this male Baltimore Oriole during my travels in Missouri and Southern Illinois. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Because of the natural forest dynamics here, this forest, with time, will transition to beech and maple unless there is human intervention in the form of prescribed fire and thinning. It is fascinating to see that the forest needs to be purposefully disturbed to allow oak seedlings to grow successfully into canopy trees.

A Champion Tree

After a morning of intensive learning about managing forests for Cerulean Warblers and Wild Turkeys, I visited the Cache River State Wildlife Area. While exploring a cypress swamp at Heron Pond, I saw two cottonmouth snakes in the water not far from the boardwalk. I also visited a “state champion” cherrybark oak with a diameter of more than five feet.

This cherrybark oak at Cache River State Wildlife Area had a diameter of more than five feet. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Historical actions and ongoing human disturbance in the Cache ecosystem threaten to degrade the wetlands that make this place so special. What I am learning is that conservationists and foresters have to fight the good fight to see that management of forest and water preserves the natural benefits these places offer to migratory birds and other native plants and animals.

Open Woodlands

The next day, accompanied by ABC's Larry Heggemann, I visited Wildcat Bluff, in the Cache River ecosystem, and Simpson Creek Barrens. These are both upland sites where forest managers are using fire and selective thinning of the forest canopy to emulate the natural disturbances that historically shaped these open woodland communities.

Forest management creates open woodlands favored by the Prairie Warbler. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Though not as stately as mature forest, open oak woodland habitats provide critical foraging and nesting cover vital to many declining grassland-shrub and savanna bird species like Red-headed Woodpecker, Prairie Warbler, and Yellow-breasted Chat.

Warblers in the City

After leaving southern Illinois, I traveled on to camp just north of St. Louis at Pere Marquette State Park. My plans were to visit an urban “migrant trap” in downtown St. Louis. Many U.S. birders see most of their warblers in an urban setting, so I thought it would be useful to experience this firsthand along the Mississippi with those who know their stuff.

I stood on the spot where the Missouri meets the Mississippi. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Tower Grove Park, in the center of the city, is a prime spot. Urban parklands like this provide joy for local birders as well as critical stopover habitat for migrants passing through. I was with several local birders, and by 9 a.m. we racked up 54 species.

Highlights were a sighting of Black-throated Blue Warbler, as well as Philadelphia Vireo and Olive-sided Flycatcher. The concentrating effects of a large urban expanse were obvious here, as we had migrant species in numbers that I was not seeing in the heavily wooded state parks.

May 25, 2015 Blog #18 of my North with the Spring journey:

The bubbling song of the Bobolink greeted me in northern Illinois. Photo by Bruce Beehler

As I travel past St. Louis, I am now in the northern half of my journey. I know this because I have left behind the Carolina Chickadee for the Black-capped Chickadee, and I have lost the Fish Crow and Black Vulture. Instead, while birding the hayfields of northern Illinois, I now hear the exciting bubbling song of the Bobolink. Nesting Bobolinks tell me I am in the North! So long, cypress and cherrybark oak!

Testing a Theory

For much of the drive up, I followed the Illinois River valley, which is broad and agricultural but hemmed in by handsome wooded bluffs. Black locusts bloomed in profusion. Late in the morning, I caught sight of a beautiful big male coyote standing in the stubble of a corn field.

A tidy farm in northern Illinois. Photo by Bruce Beehler

I decided to camp two nights at Argyle Lake State Park, a small park situated some 30 miles east of the Mississippi. I wanted to see if a small and isolated woodland park in open farmland would produce a greater concentration of migrant songbirds on passage north.

Argyle is a hilly patch of oak woods surrounding a small, dammed lake. I had two good mornings for birding to test my theory: Lots of migrant Tennessee Warblers, a Canada Warbler, Rose-breasted Grosbeaks, Scarlet Tanagers, and Swainson's Thrushes. Also there were resident breeders—singing Kentucky Warblers and Ovenbirds. Still, I was hardly overwhelmed by the numbers of migrants in the woods. So much for my theory!

I saw Scarlet Tanagers in a hilly patch of oak woods at Illinois's Argyle Lake State Park. Photo by Greg Lavaty

Not far from Argyle Lake is a restored patch of prairie at Spring Lake Park. I visited early in hopes of Henslow's Sparrows and Upland Sandpipers. Instead, I saw Bobolinks, Dickcissels, and too many Red-winged Blackbirds to count. From here, I made tracks for my last stop in Illinois: Mississippi Palisades State Park.

At Spring Lake Park, I saw this male Dickcissel in a restored patch of prairie. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Last Look at Summer Tanagers

Mississippi Palisades resembles a northern version of Missouri's Pere Marquette State Park, featuring bluffs with scenic views of the great river. Hooded Warblers were on territory in the upland woods, and migrant Tennessee Warblers and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks were noisy in the canopy.

A Wild Turkey hen in northern Illinois. Photo by Bruce Beehler

About seven miles up the road was the Lost Mound Unit of the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge. The area supports extensive prairie openings—all across a former U.S. Army Depot. From a river overlook set on a 70-foot natural sand dune, I watched a small group of White Pelicans and several adult Bald Eagles. This is the last place I will see Summer Tanagers, who don't make it as far north as my next stop in Wisconsin.

June 3, 2015 Blog #19 of my North with the Spring journey:

I saw this Sedge Wren at Crex Meadows Wildlife Area, in Wisconsin. Photo by Bruce Beehler

In the southwestern corner of Wisconsin, where the Wisconsin River meets the Mississippi, there are a series of high bluffs that hem in these two great rivers. The bluff south of the Wisconsin is called Wyalusing, and is home to a superb state park. I camped there for four nights, and biked and birded the park and adjacent natural areas in both Wisconsin and neighboring Iowa.

A Grasshopper Sparrow in Wisconsin. Photo by Bruce Beehler

I found lovely oak forests and deciduous bottomlands near the confluence of the rivers. A male Cerulean Warbler serenaded me from just over my tent site morning and afternoon. American Redstarts played around every patch of woodland, often foraging nearly to ground level in pairs. Henslow's Sparrows gave their asthmatic call from a large grassland patch near the center of the park. And Bell's Vireo sang its crazy song from a row of trees in an open oak glade. Dozens of northward-traveling Tennessee and Blackpoll Warblers enlivened the canopy oak trees.

Ancient Mounds

This part of the Mississippi is famous for its American Indian Mounds. These are ancient mounds that Native Americans built for funerary or ceremonial purposes. There are several thousand mounds scattered across much of the East, but the Mississippi mounds are the most famous, perhaps because some of them are formed in the shape of animals.

Migrant birds like American Redstart filled the woodlands of Effigy Mounds National Monument, in Iowa. Photo by Greg Lavaty

I visited Effigy Mounds National Monument just across the River in Iowa on my first afternoon here. Over the centuries, the forest has grown up around these mounds, so I experienced the best of these remarkable historical features in a woodland setting. I was particularly moved by the mounds shaped like bears. The area also was filled with migrant birds—especially Rose-breasted Grosbeaks and American Redstarts.

Once Forest, Now Prairie

A birder from North Dakota whom I met in Wyalusing State Park mentioned that I should visit Crex Meadows, near Grantsburg, Wisc., in the far northwest part of the state. Crex Meadows Wildlife Area is an amazing natural site of 30,000 acres that has been heavily managed to bring it back to what is thought to be its primeval prairie state.

At Crex Meadows, fire and mechanical means have transformed closed-canopy deciduous forest into prairie. Photo by Bruce Beehler

There is no conservation area on my travels that has received smarter management than Crex Meadows. The result is positive: Sandhill Crane pairs were scattered all through the marsh and prairie setting. I found Trumpeter Swans, Whip-poor-will, Common Raven, Sedge Wren, Alder Flycatcher, Clay-colored Sparrow, and Mourning Warbler.

Crex Meadows is home to many nesting pairs of Sandhill Cranes each summer. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Several wolf packs inhabit this part of Wisconsin, and I saw tracks in the soft sand. This vast open mix of prairie and marshland is a wonderful reminder of the way things used to be, before the long period of fire-suppression and the dominant regeneration of former prairie into deciduous forest.

Trumpeter Swans at Crex Meadows. Photo by Bruce Beehler

The Far Northeast

Looking at a map of Wisconsin, I decided to head to an area with hundreds of small lakes in the state's far northeast, near the border with the upper peninsula of Michigan. Known locally as the Northern Highlands, this area had an abundance of balsam fir, white and black spruce, and tamarack, as well as sphagnum bogs. It reminded me of the northern Adirondacks.

I saw this Mourning Warbler in northeastern Wisconsin, in an area known as the Northern Highlands. Photo by Bruce Beehler

The highlands also featured Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers, giving their cadenced drum; Ovenbirds; Mourning and Nashville Warblers; Hermit Thrushes; and Lincoln's Sparrows. Now I was in the far north—the southern edge of the Great North Woods! From here, I plan to head west into Minnesota, my last stop before heading into the wilds of Canada.

June 3, 2015 Blog #20 of my North with the Spring journey:

Upland Sandpiper at Felton Prairie, a carefully managed remnant prairie in northern Minnesota. Photo by Bruce Beehler

From northern Wisconsin, I traveled west to Minnesota and the north shore of Lake Superior. Based out of Gooseberry Falls State Park, about an hour northeast of Duluth, my wife Carol and I toured the boreal forests of this marvelous area.

The first night, on the way in from the airport, Carol saw a silvery timber wolf on the roadside as we drove along highway 61. White spruce and aspens marked our campsite, where Ruby-crowned Kinglets, Chestnut-sided and Yellow-rumped Warblers, and White-throated Sparrows serenaded us each morning. Temperatures hovered near freezing at dawn, and strong winds blew off Lake Superior. Ground squirrels, red squirrels, and chipmunks visited us at our picnic table for treats.

At our picnic table, we had visitors like this ground squirrel. Photo by Bruce Beehler

In the interior, which we visited each morning, we heard Ruffed Grouse drumming and chased down boreal warblers—Nashville, Tennessee, Canada, Magnolia, Black-throated Green, Mourning, Yellow-rumped and more. Sadly, we missed Connecticut Warbler.

North of Duluth, we saw many warblers, including Mourning Warbler. Photo by Bruce Beehler

Headwaters of a Great River

At Itasca State Park's 32,000 acres of natural habitat, I was amazed to see the headwaters of the Mississippi. They were no more than a few yards wide, winding among a mix of lakes, bogs, and mixed-boreal forest. Right at the headwaters a lovely adult male Black-backed Woodpecker surprised us, flying to a large white spruce and allowing us to gaze for more than a minute at this rare creature.

We saw a Black-backed Woodpecker in Itasca State Park, near the headwaters of the Mississippi River. Photo by ShutterShock

The following day we wandered westward, to Felton Prairie, where in spite of strong winds we successfully searched out Upland Sandpiper and Greater Prairie Chicken. This wide-open expanse of prairie was quite a change from the closed boreal forest I had been birding the previous several days. As with Crex Meadows, this lovely remnant prairie is carefully managed, especially with periodic fire, to maintain its special qualities that the birds love.

Searching for Woodcock

My last birding day in Minnesota was spent at Tamarac National Wildlife Refuge. Tamarac's 40,000 acres are a mix of lakes, marshes, bogs, and mixed upland forests, and targeted habitat management is enriching its songbird and wildlife values year by year.

There I visited with Peter Dieser and Earl Johnson. Peter is an ABC field staffer working on habitat improvement for Golden-winged Warbler and American Woodcock. Earl Johnson is a retired state wildlife biologist who now works on banding and surveying American Woodcock. We went afield in search of these two elusive species.

Golden-winged Warbler have responded quickly to habitat management at Tamarac National Wildlife Refuge in Minnesota. Photo by Laura Erickson

Earl quietly showed us a nesting woodcock hen sitting on four eggs. It was amazing to see how camouflaged the sitting bird was—Earl spent quite some time describing where this bird sat in the grassy tangle before I could actually see it.

I saw various patches of forest that had been managed for these two species, which love early successional woodland and forest openings. I was amazed to see how effective this management could be in such a short time: One patch, treated two years ago, was filled with singing male Golden-wings. Another site, treated only a year ago, supported a singing male goldenwing and nesting woodcock. Build the habitat and they will come!

Note from the editor: Thank you so much for joining ABC Field Naturalist, Bruce Beehler, on his journey "North with the Spring." Stay tuned for highlights from his epic adventure in a post-trip wrap-up later this summer.